When Parallel Lives Overlapped: Alexander Calder and Marino Marini

Olivia Armandroff Olivia Armandroff Marino Marini, Issue 5, May 2021https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/marino-marini/

Alexander Calder and Marino Marini first encountered one another in 1950, during the Italian sculptor’s first visit to America. After this initial meeting, the two artists would continue to exchange correspondence for several years, especially during Calder’s participation in the 1952 Venice Biennale. Their social interactions developed out of their mutual friendship with and shared representation by the dealer Curt Valentin. As a result, both artists’ works were collected by the same patrons and displayed in spaces alongside one another, for example in Peggy Guggenheim’s Venice collection and that of Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., the owner of Fallingwater. Although art historical narratives have frequently focused on Marini as a sculptor looking backward, fascinated by the antique, and on Calder as an avant-garde innovator, breaking with traditional definitions of form, the similarities between the two artists—in their subjects and innovative techniques—demonstrate how both were men reflecting on their contemporary era. This article reflects upon surviving archival evidence from both the Calder Foundation and the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia that illustrates their friendship.

Art historical narratives have frequently framed Marino Marini as a sculptor looking backward, fascinated by the antique. In contrast, stories told about his contemporary Alexander Calder emphasize him as an avant-garde innovator, breaking with traditional definitions of form. While Calder’s mobiles thwart gravity, Marini’s sculptures have a weighty presence, or a solidity, and are firmly linked to the ground through the inspiration the artist derived from buried Etruscan antiquities. In some ways, both became standard-bearers for national identity: Marini engendering a second renaissance of Roman mythology and humanistic thinking; Calder wearing the mantle of American revolutionaries, with their rebellious nature and even youthful playfulness. A comparison between the two artists might initially appear incongruous, but the similarities between them are deeper than their two reputations might suggest. Both Marini and Calder catered to the same patrons, featured common subjects, and experimented with a wide range of techniques beyond sculpture, including print media. In truth, both men offered modern interpretations of historic traditions. If they were not directly influenced by one another, it seems possible these harmonies are indicative of how both men reflected their contemporary era’s preoccupations and concerns. Born three years apart, and dying within four years of one another, these two artists lived parallel lives on their respective continents.

Marini and Calder were attracted to similar subjects. Marini’s consistent return to acrobats and jugglers mirrored Calder’s lifelong fascination with the circus. Both artists were similarly invested in animals as subjects, and while Calder was responsible for a more diverse sculpted menagerie, he depicted horses and equestrian subjects like Marini, who made the theme his life’s concentration. These preoccupations were not unique to Calder and Marini, but were instead part of a shared visual language of European modernists, reflecting the precedents set by earlier artists, especially Pablo Picasso.1

While art historical literature has increasingly differentiated between the work of Marini and Calder through time, connections were recognized by their contemporaries. Calder and Marini were collected by the same patrons and shared the same spaces of display, as in the collection of Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., the owner of the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed house Fallingwater, in Mill Run, Pennsylvania. Kaufmann displayed his horse and rider by Marini outside, under the cantilevered section of the house that hovers over Bear Creek, while Calder’s mobile, Little Tree (1942), was also part of Kaufmann’s collection.2 Peggy Guggenheim was also a powerful patron and advocate for both artists. She introduced Italians to Calder’s work in 1948, when her collection of modern sculpture was exhibited in Venice.3 As a result of the exhibition, Guggenheim chose to purchase the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in Venice the following year.4 To inaugurate the space as one of display, Guggenheim organized a contemporary sculpture exhibition in the garden in 1949, where Calder’s work was again displayed. But Guggenheim chose to show Italian sculptors, including Marini, in addition to those sculptures she had previously collected.5 The Calder mobile Arc of Petals (figure 1), from 1941, appeared alongside Marini’s L’angelo della città (The Angel of the City; figure 2), which had just been completed in 1948. Today, in accordance with Guggenheim’s original placement, Marini’s sculpture stands guard on a terrace over the canal-side entrance to the museum. Inside, in the central hall, visible in juxtaposition to the equestrian sculpture, Calder’s mobile Arc of Petals has historically been displayed. As two significant anchors to the museum’s collection, these pieces have been in conversation for decades. Viewers throughout the institution’s history could follow the outstretched arms and inclined torso of Marini’s rider with their eyes, gazing upward toward the central hall’s ceiling, from which Calder’s mobile playfully rotates.

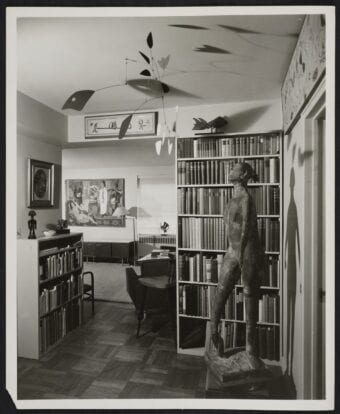

In the period when Guggenheim was drawing a connection between Marini and Calder, the dealer Curt Valentin was making a similar association. Valentin came to represent Marini as his dealer in New York City, and in 1950 he hosted the first solo exhibition of Marini’s work at his Buchholz Gallery.6 Valentin was an immigrant from Berlin and known for his roster of European modernist artists – including Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Juan Gris – and he fostered these connections in annual collecting tours on the continent.7 But Valentin also long represented Calder, having given him his first solo exhibition, in 1944. In his autobiography, Calder described his unique collaboration with the dealer, noting that Valentin represented few Americans. An archival photograph of Valentin’s apartment (figure 3) demonstrates that he, like Guggenheim, saw aesthetic similarities between the two artists: one of Marini’s Pomonas, a series of sculptures dedicated to the female nude and, in name, the Etruscan goddess of fertility, is positioned beneath a Calder mobile.8 The Pomona’s upturned gaze again draws a connection with the overhanging work. In the photograph, the shadows of the two art pieces on the wall bring the works even closer together.

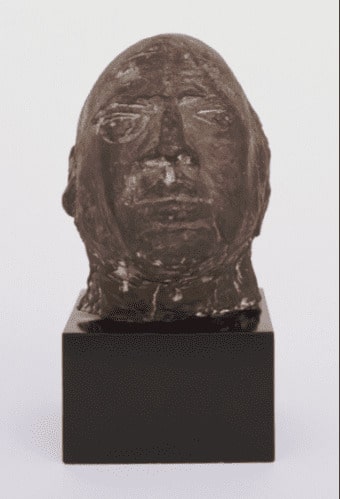

The significance of Valentin in both Calder’s and Marini’s lives is documented by the visual memorials both artists made to their shared dealer. Calder created a 1944 drawing of Valentin, now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.9 The wiry, black ink lines and concentric circles framing Valentin’s eyes recall Calder’s curvilinear wire sculptures from the time, equating the dealer with the artwork he was responsible for on behalf of Calder. Marini’s dedication to Valentin is evident in the sculpture he made of him in 1954 (figure 4), a bronze head that now resides in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. In these efforts, Calder and Marini were not alone, and other artists who built friendships with and relied upon Valentin, such as André Masson, honored him with portraits as well.10

Valentin was responsible for fostering a personal connection between Marini and Calder. For Marini’s 1950 exhibition at the Buchholz Gallery, the Italian sculptor embarked on his first and only trip to the United States. During this visit, Calder and his wife, Louisa, invited Marini to their home in Roxbury, Connecticut.11 After this encounter, the two artists would continue to cultivate their relationship through correspondence that was friendly and conversational in tone. Collections in the Calder Foundation and the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia chronicle this friendship.

The first in their preserved series of correspondence dates from 1951, when Calder wrote in Italian to Marini and his wife Marina, attributing his decision to study the language to their visit to his home in Roxbury.12 Subsequent exchanges remained fond. In 1952, Calder sent the couple a postcard featuring a technicolor image of the Statue of Liberty.13 On the back he playfully wrote in Italian again, drawing an image of a fish. Not long after, Calder had reason to visit Italy and practice his Italian. In 1952, he represented the United States in the Venice Biennale, winning the grand prize for sculpture.14 For this, Marini wrote a postcard to Calder, congratulating him on his success.15 Calder responded with a lengthy letter in French in November of that year, mentioning the compliments he received for the award but admitting he didn’t understand the Biennale or Italian taste.16

The correspondence between the two artists continued into 1953.17 But Calder and Marini had a new reason to write in 1954, when Valentin visited Italy in the summer. Photographs of Marini and Valentin, presumably from this trip, are a part of the papers of Valentin and his assistant Jane Wade Sabersky, held by MoMA and the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.18 The trip ended suddenly when Valentin suffered a heart attack and passed away. Marini attended the funeral and corresponded with the dealer’s global contacts. Wade informed Calder of Valentin’s untimely death, and Calder in turn wrote to Marini, expressing his sorrow and sympathies and admitting he had not seen Valentin in a year.19 Marini would respond to Calder, sending him a letter that chronicled the funeral in Italy.20

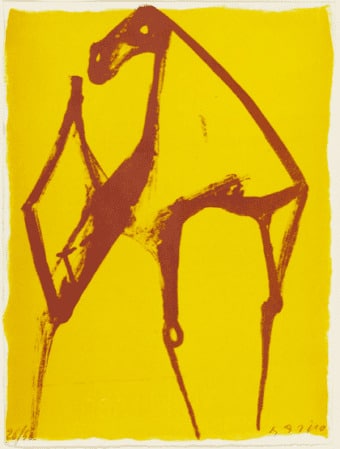

Wade corresponded with others, too, regarding Valentin’s death and Marini’s involvement in the funeral, including Will Grohmann, the German art critic.21 In his letter, Grohmann proposed a memorial publication honoring Valentin. For its frontispiece he proposed the portrait of Valentin by Marini, requesting that Wade send him a good image of the sculpture. Marini’s bust was not simply recognized by the friends and companions of Valentin as a means of remembering and commemorating the dealer: the following year, Marini donated the bust to the MoMA, likely in honor of Valentin’s death. In a similar way, Valentin posthumously honored the artists whom he had represented: in 1956 his collection entered MoMA’s, including a lithograph of Marini’s Cavallo (Horse, 1952 figure 5). Valentin’s gift on behalf of Marini and Marini’s gift on behalf of Valentin remain together in the collection today.

There is little evidence of a continued connection between Calder and Marini after Valentin’s death. A final exchange is documented in the collection of the Calder Foundation: in May of 1955, the two artists corresponded, and Marini asked when they would see one another again.22 Calder eventually returned to Italy to engage in a series of projects in Spoleto, first in 1958, to construct sets for a ballet to be performed during the Festival dei Due Mondi (Festival of Two Worlds), and again in 1962, to complete a fifty-eight-foot-tall stabile, Teodelapio, for the Spoleto Festival.23 For the project, Calder developed a closer relationship with the Italian art critic Giovanni Carandente, also a personal friend of Marini, who recommended Calder for subsequent commissions, among them to develop a work for the stage of the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome, working with the artistic director Massimo Bogianckino.24 Yet during these trips, there is no record of Calder and Marini reuniting. Despite this, the two artists would have remained aware of one another, likely following one another’s careers from afar, until Calder’s death in 1976.

Ultimately, Calder and Marini were concerned with similar subjects and exhibited a common investment in experimentation. Their representation by the same gallerist, their patronage by certain collectors, and their mutual connections to figures in the art world suggest that both artists appealed to a distinct set of tastes in the mid-twentieth century. Both crossed the Atlantic and toured one another’s countries. While they had few personal interactions, it seems that both artists exhibited the ethos of their era. Responding to the demands of their time, Marini and Calder were typical of the modern artist, especially the modern sculptor.

Bibliography

Calder Foundation. “Exhibitions.” Accessed November 11, 2020. http://www.calder.org/life/exhibitions.

Calder Foundation. “Work, By Life Period.” Accessed November 11, 2020. http://www.calder.org/work/by-life-period/1946-1952.

Cinelli, Barbara, and Flavio Fergonzi, eds. Marino Marini: Visual Passions: Encounters with Masterworks of Sculpture from the Etruscans to Henry Moore. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2017.

Gamble, Antje K. “Buying Marino Marini: The American Market for Italian Art after World War II.” In Postwar Italian Art History Today: Untying “the Knot,” edited by Sharon Hecker and Marin Sullivan, 155–225. New York: Bloomsbury, 2018.

Hollevoet-Force, Christel. “Valentin, Curt.” Index of Historic Collectors and Dealers of Cubism, Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art. March 2018. Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/libraries-and-research-centers/leonard-lauder-research-center/research/index-of-cubist-art-collectors/valentin.

Marchiori, Giuseppe. Giardino del Palazzo Venier dei Leoni. Venice: Settembre, 1949.

Peggy Guggenheim Collection. “Marino Marini: Artist.” Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/art/artists/marino-marini/.

Sperling, L. Joy. “The Popular Sources of Calder’s Circus: The Humpty Dumpty Circus, Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey, and the Cirque Medrano.” Journal of American Culture 17, no. 4 (Winter 1994).

Sweeney, James Johnson. Alexander Calder. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1943. Exhibition catalogue.

Vail, Karole P. B., and Vivien Greene. Peggy Guggenheim: The Last Dogaressa. Venice and New York: Peggy Guggenheim Collection and Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2019.

- See L. Joy Sperling, “The Popular Sources of Calder’s Circus: The Humpty Dumpty Circus, Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey, and the Cirque Medrano,” Journal of American Culture 17, no. 4 (Winter 1994): 1; Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi, eds., Marino Marini: Visual Passions: Encounters with Masterworks of Sculpture from the Etruscans to Henry Moore (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2017), 118.

- See Antje K. Gamble, “Buying Marino Marini: The American Market for Italian Art after World War II,” in Postwar Italian Art History Today: Untying “the Knot,” ed. Sharon Hecker and Marin Sullivan (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018), 159; and James Johnson Sweeney, Alexander Calder (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943), 49, accessed January 20, 2021, https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2870_300191625.pdf.

- Gamble, “Buying Marino Marini,” 159.

- Karole P. B. Vail and Vivien Greene, Peggy Guggenheim: The Last Dogaressa (Venice and New York: Peggy Guggenheim Collection and Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2019), 129.

- Giuseppe Marchiori, Giardino del Palazzo Venier dei Leoni (Venice: Settembre, 1949).

- “Marino Marini: Artist,” Peggy Guggenheim Collection, https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/art/artists/marino-marini/.

- Christel Hollevoet-Force, “Valentin, Curt,” Index of Historic Collectors and Dealers of Cubism, Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 2018, accessed January 19, 2021, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/libraries-and-research-centers/leonard-lauder-research-center/research/index-of-cubist-art-collectors/valentin; Alexander Calder, Calder: An Autobiography with Pictures (New York: Pantheon Books, 1966), 194.

- “Alexander Calder, Curt Valentin, 1944,” National Gallery of Art, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.92749.html.

- The portrait can be seen at “Alexander Calder, Curt Valentin, 1944,” National Gallery of Art, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.92749.html.

- “André Masson, Curt Valentin, 1946,” National Gallery of Art, accessed January 20, 2021, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.34004.html.

- Gamble, “Buying Marino Marini,” 159.

- Alexander Calder, letter to Marino Marini, 1951, Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia. Access to this and other correspondence in the Fondazione Marino Marini was made possible by the generosity of Flavio Fergonzi, who took images in the archive. I am also grateful to Michele Amedei, Nicol Mocchi, and Claudia Daniotti for coordinating my receipt of the images.

- Calder, postcard to Marini, 1952, Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia.

- “Work, By Life Period,” Calder Foundation, accessed November 11, 2020, http://www.calder.org/work/by-life-period/1946-1952.

- My thanks goes to Beryl Gilothwest at the Calder Foundation for answering my inquiries and relating the connections between the two artists in the archival collection during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Calder, letter to Marini, November 7, 1952, Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia.

- Calder, letter to Marini, 1953, Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia.

- See Jane Sabersky papers, 1940–1972, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, accessed January 20, 2021, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/jane-sabersky-papers-5690#overview. See also photograph of Curt Valentin, Photographic Archive, Artists and Personalities, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, accessed January 20, 2021, https://maid.moma.org/#/detail/232546?index=30&search={%22searchKeyword%22:%22valentin%22}&sort=[[%22objectNumber%22,%22asc%22]]&gridType=list.

- Calder, letter to Marini, 1954, Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia.

- Again, I am indebted to Beryl Gilothwest for describing this letter held by the Calder Foundation

- Correspondence from Will Grohmann to Jane Wade, August 25, 1954, Jane Wade papers regarding Curt Valentin, 1903–1971, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, accessed January 20, 2021, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/letter-will-grohmann-to-jane-wade-about-death-curt-valentin-15344.

- Beryl Gilothwest provided information about this letter from Marini to Calder, written on May 28, 1955 and held by the Calder Foundation.

- “Work, By Life Period,” Calder Foundation, accessed November 11, 2020, http://www.calder.org/work/by-life-period/1946-1952.

- “Exhibitions,” Calder Foundation, accessed November 11, 2020, http://www.calder.org/life/exhibitions.