Photographing Sculpture: A Comparison between Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù from 1930 to 1950

Flavio Fergonzi Flavio Fergonzi Marino Marini, Issue 5, May 2021https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/marino-marini/

This essay examines the crucial role that photography played in the affirmation and critical interpretation of Marino Marini (1901-1980) and Giacomo Manzù (1908-1991), two of Italy’s foremost modernist sculptors. Through a close comparison of photographs published in books, art journals, and magazines, the author demonstrates how the choices that photographers make when portraying sculpture greatly influence the legibility of a work. The importance of photographic reproduction became particularly evident in Italy during the 1940s: given the constraints that World War II imposed on the travel of artworks and the organization of art exhibitions, the circulation of photographs was a pivotal instrument in establishing the reception of Marini’s and Manzù’s sculptures, with significant reverberations in the postwar era. The photographers’ choices in terms of angle, cropping, backgrounds, and lighting thus provided a first, critical reading that is here thoroughly studied over the course of three decades.

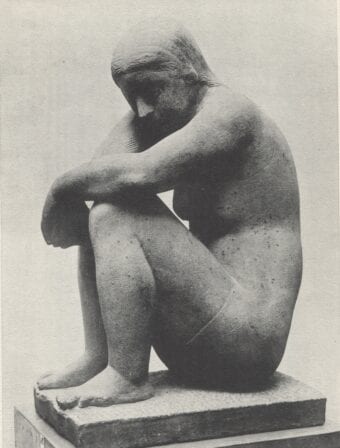

Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù entered the period after World War II as the two foremost Italian sculptors. They represented opposite stylistic declinations, both easily recognizable as quintessentially Italian: Marini’s style was characterized by attention to iconographic archetypes (the horse rider, the female nude) as well as plastic (archaic simplification, synthesis of volumes), and linked to archaeological traditions and Tuscan art; Manzù instead focused on the dialogue between painting and “painterly” sculpture (a line that leads from Leonardo da Vinci to Medardo Rosso), with all the implications of psychological rendering that such a positioning involves. The sudden passing in 1947 of Arturo Martini, an artist whose work had kept open both approaches – and whom, for this reason, had been accused of “eclecticism” since the end of the war – facilitated the aforementioned polarization.1

The fame of Marini and Manzù was defined and affirmed even thanks to the photographs that were taken of their works; this was the case particularly during the war years, decisive in Italy for the reinterpretation, according to new hierarchies of value, of Italian art history since the start of the century. At this time, especially between 1942 and 1945, the transportation of artworks was expensive and often risky, and thus exhibitions became few and far between. However, the difficulty of analyzing works in person paradoxically provided more time to reconsider their value, and here the crucial role of photographic reproductions came into play. In these dramatic years, photographs traveled widely, in envelopes that artists mailed to editors, gallery owners, collectors, and art critics, and also – even more pervasively – in books, which brave editors continued to publish (or, after 1943, continued to plan, with printing deferred until after the war’s end). Whereas photography can be seen to engender a betrayal of painting (one must recall, in the same years, the collector Pietro Feroldi’s obsession with trichromes that would present true-to-life tonal values of Carlo Carrà’s or Giorgio Morandi’s paintings),2 photography does not subtract but rather adds information to sculpture. The lighting, camera angle, and focus all affect the view in a printed reproduction, for instance a photographic illustration in a book; at the very least, photography facilitates, in a decisive way, the artwork’s interpretation.3

In turning to photographs to examine the relationships of works by Marini and Manzù, two distinct issues must be addressed. The first concerns the relationship between the sculptor and the photographer. Unfortunately, we know very little about the conversations that took place when photographers visited these two sculptors’ studios and placed their cameras in front of their art. What occurred when either sculptor brought a statuette or a head to a photographer’s studio to have it reproduced? Certainly it must have been the sculptor who suggested the point of view and the framing angle, and perhaps he also chose the backdrop. But one wonders, could the sculptor control more technical aspects, like the aperture, exposure time, the positioning of the lights, or the relationship between the different focal planes? It was surely necessary for the photographer to establish a relationship of trust with the sculptor. In two important books published during the war years about Marini and Manzù respectively, the photographer’s name is included in the colophon, indicating a role far more important than was usual at the time (the credit was typically indicated in small print, in parentheses, under a photograph – though this was not always the case). In the 1941 volume Marino that is introduced by Filippo de Pisis, photographs by Gianni Mari act as a stylistic binder between very different sculptures; Manzù, published in 1943 by Editoriale Domus, with an introduction by Nino Bertocchi, specifies that Attilio Bacci’s photographs were taken “in collaboration with the author.”4 Both books in fact include images shot by other photographers who are not thus mentioned, supporting the assertion that these annotations regarding Mari and Bacci are fundamental.

It was usually the sculptor who paid the photographer for his expertise and service, almost never the editor, as is documented, for instance, in the Scheiwiller Archive, in letters that mention invoices sent by accident from the photographer to the editor, who then forwarded them to the artist. For a sculptor, hiring a photographer was a recurring expense required so that a work could to be shown around and thus become recognized. Only on the occasion of a major exhibition (the Venice Biennale or the Rome Quadriennale), or when a piece became part of a public collection, would the photographer be employed by the institution (in these cases, the sculptures tend to end up looking all a bit similar, as can be seen in the photographic documentation of various works exhibited at the Biennales by the Reale Fotografia Giacomelli in Venice). In the 1930s, magazines commissioned (including paying for) an increasing number of photo shoots of sculptors’ studios, often featuring picturesque clusters of artworks much like protagonists. But these activities, while important, are beyond the scope of the present study.

The second question, regarding the use of photographic prints in publishing, is more easily examined. Today, the archives of editors who published books on Marini and Manzù (I conducted research in the Scheiwiller Archive and at Editoriale Domus, both in Milan) often preserve photographs that were set aside as well as the correspondence of an editor and artist – materials that are helpful in reconstructing the visual direction underlying a book. But the most revealing hints are found in flipping through the books themselves: exclusions and inclusions speak volumes, as does the photographic framing, the erasure of backdrops, and the sequencing of different points of view on the same work. After 1950, following the early postwar years, Marini’s and Manzù’s photographic image was stabilized: the photographs and photographic apparatuses of later books would serve to accentuate the sculptural specificities and the mutual differences between the two. Accordingly, it is useful to examine photographic representations of their respective works over the two decades in which their fame was substantially built and consolidated, from 1930–50. In these two decisive decades, the notion of a “Marini function” and a “Manzù function” in the evolution of Italian art in the twentieth century was formed. Moreover, it can sometimes be more revealing to interrogate photographs rather than critical texts about artists, if only because texts are often written with photographs at hand instead of original artworks, and because many of the interpretive paths to reading works are determined through the close alliance of the artist’s eye and the photographer’s.

2.

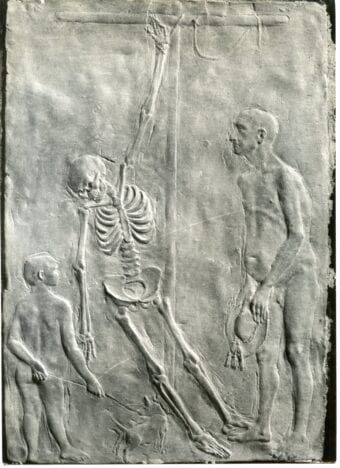

There is a pivotal date in the first half of twentieth-century Italian sculpture: 1930. In November of that year, eleven sculptures (and three ceramics) by Arturo Martini were reproduced in an article by Lionello Venturi in L’Arte, the oldest journal on Italian art history.5 In January 1931, Martini’s exhibition at the First Quadriennale in Rome, with some of the works anticipated photographically by Venturi, shattered the expectations of those who had seen in Italian sculpture of the 1920s a gradual reconquest of decorative order. The challenge for photographers was entirely unexpected: it was not necessary to show, through photographs, the sculptor’s coherence of style, but rather the unusually wide range of his expression; the relationship between a detail and the whole was to be investigated, as was the artist’s touch with relation to the intrinsic properties of the material, whether terracotta, wood, or plaster. Martini’s work exhibited a richness of plastic motifs that was basically paralyzing for any photographer; indeed, it seemed impossible to select a primary point of view from which to photograph the sculpture.

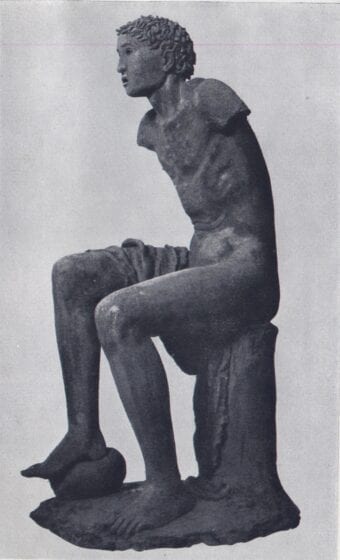

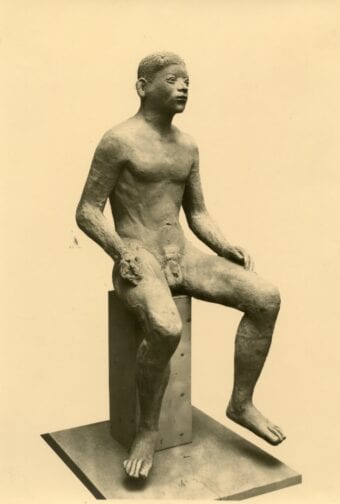

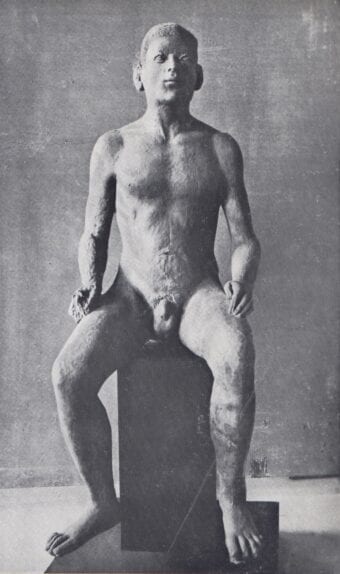

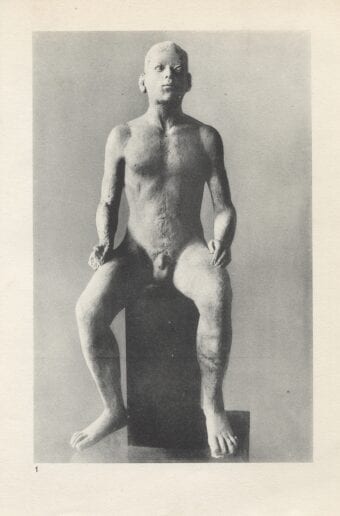

The photographer Arnaldo Maggi, from Savona, who documented the terracotta sculptures La madre folle (Insane Mother, 1929) and Ragazzo seduto (Sitting Youth, 1930), which had just been forged in the kiln of ILVA in Vado Ligure, solved this issue through multiple shots from various – frequently opposite – points of view. The anonymous photographer who captured Maternità (Maternity, 1929), roughly sculpted in wood in Monza, did the same. The most important factor is that Venturi included, as the photographic accompaniment to his essay, shots of the same artwork captured from different angles. In the case of Ragazzo seduto, he opted to include two opposite profile views (figures 1 and 2), thereby obtaining a strange play of mirroring images. Further, he renounced a view taken from the back, perhaps deeming it too archaeological, as well as an intense frontal close-up of the torso, which he may have considered insufficient to account for the sophisticated overall design of the statue (figures 3 and 4).

How was modern Italian sculpture photographed before 1930? How were books or lengthy monographic journal articles about sculptures produced? Here we must attempt to gain an understanding of the revolution brought on by Martini around 1930, which would reverberate in photographic reproductions of Italian sculpture in the following decades.

Let us look at two photography books (in reality, folders of unbound folio-size photographic prints) dedicated to the two major Italian sculptors of the 1910s and 1920s: Leonardo Bistolfi, published in 1911, and Adolfo Wildt, in 1926. For Bistolfi’s works, the photographer (or multiple photographers), sought subtly atmospheric, tonal reproductions of sculptures set outdoors, inserting the works in an almost disturbing way in the landscape, whether rural, urban, or cemeterial.6 For plaster sculptures photographed in the studio, the backdrop was invariably black; crudely illuminated by lamps and framed frontally or, more rarely, in profile, these large sculptures stand out like white ghosts destined to lose the consistency of reality. This mode of representation was the fallout of the model imposed by Judith Cladel’s recent and successful book on Auguste Rodin,7 for which the large artworks were photographed by Jacques-Ernest Bulloz as definite forms against a black background, while preparatory studies and smaller bronzes were photographed by Eugène Druet against recognizable settings and backgrounds.

The photographs by Emilio Sommariva and Antonio Paoletti published in the Wildt book, in1926, mostly demonstrate the examination of the linear meaning of marble sculptures.8 Precious arabesque profiles are emphasized against a deep black backdrop, and the camera frequently moves to perform a progressive zoom, as in the exemplary case of Trilogia (Trilogy, 1912), where a sequence of shots powerfully narrow in, from the whole to a seventeenth-century-style drapery detail. The few diversions from the frontal or profile view (for example, there is one three-quarter view, for Busto di Benito Mussolini, 1923) underscore linear motifs, like the one in the lappet draped behind the neck, so much so that the passage from photographic plates documenting sculptures to plates documenting line drawings, reproduced in the last part of the book, happens organically, almost unnoticeably.

As sculpture was returning to a new classical order in the first years of the 1920s, photography rapidly adapted. In Ugo Ojetti’s journal Dedalo, reproductions of the works of Libero Andreotti or Antonio Maraini9 present a clear and incisive quality, with gray or black blackgrounds, as was typical for photographs of ancient and Renaissance sculpture (a hint of shadow on the light gray background in shots of Andreotti’s bronzes barely declares the existence of an alternative plane to those being investigated photographically in the sculptures). Bas-reliefs, with their architectural logic, were the ultimate test for photographers, and even three-dimensional sculptures can sometimes appear like reliefs in photographs.

At the beginning of the 1920s, Martini’s work had posed novel questions with respect to a style of sculpture that demanded a normalizing photographic reading. Mario Broglio realized as much, and in an issue of Valori Plastici (the third issue of the third year, 1922), he decided to publish the Pucelle d’Orléans (The Maid of Orleans, 1920) in three separate shots, from three different points of view – either as a suggestion for painters to keep in mind a figure’s development in space when depicting it, or as a surrender to the complexity of plastic invention, irreducible to a single point of view.

After 1930, reproducing Martini’s work through photography became even harder than it had been in the previous decade. Complicating matters, time and again backstories, ironic or sentimental, intervened in his sculptural practice. The tension between his sculpture’s stringent volumetric logic and its narrative content is highlighted, for example, in Maggi’s shots of Convalescente (Convalescent, 1932; figure 5). There is also the focus on details, and not backing away from the risk of appearing “pictorial”; this was the case for the anonymous Florentine photographer who focused on the face and gesture of the sculpture La Girl (Girl, 1931), exhibited at Martini’s solo presentation at Palazzo Ferroni in 1932 (figure 6).

3.

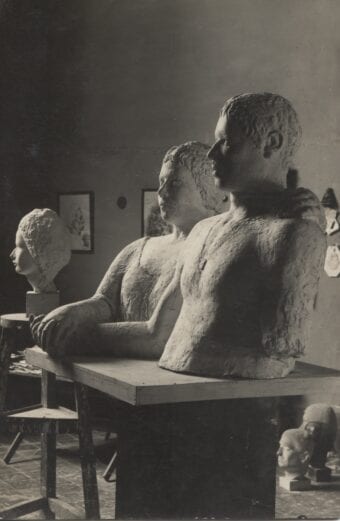

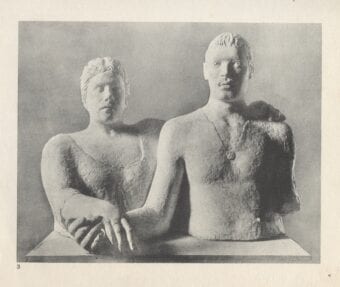

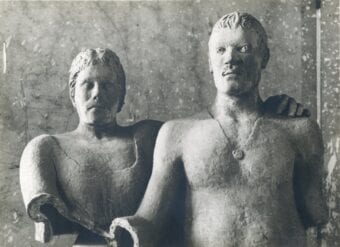

Let us now investigate some photographic reproductions of the works of Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù at the beginning of the 1930s. Both sculptors were at the beginning of their careers, although there is a slight but significant distinction to be pointed out between the two. By 1930, Marini already had a brief exhibition history, with some public sales (his Testa di giovane uomo [Head of young man, 1928 was photographed by Brogi as if it were a piece of plastic expressionism by Romano Romanelli).10 Manzù was, in 1930, still an absolute beginner. His Uomo e donna (Man and Woman, 1929-1930), a plaster work included in a group exhibition at the Galleria Milano in the spring of 1930, was captured by its photographer as if it were a relief by Maraini – sharp and unyielding in its lines, without bright contrasts that could weaken its naive design.11

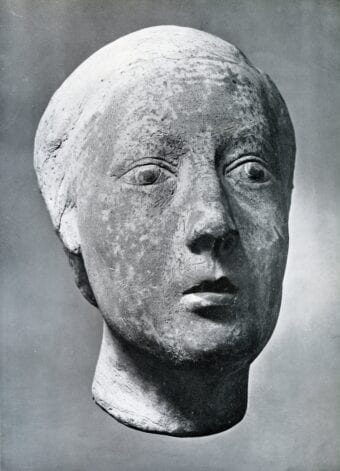

It is best to proceed by taking up similar typologies of artworks, starting with two heads and two full figures from 1932. The two Teste (one female, by Marini, and one a boy, by Manzù) are not portraits, but they fall into that particular declination of the “character” head: halfway between pure stylistic experimentation and strong anti-psychological characterization that emerges at the beginning of the decade.

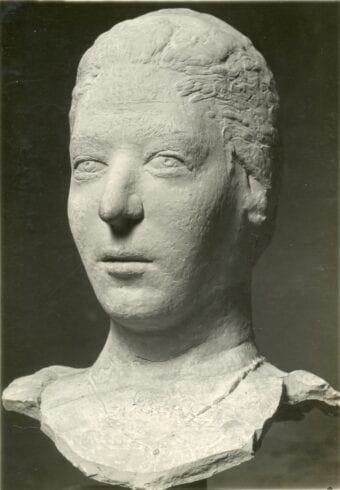

The Testa modeled in 1932 by Marini (figure 7) was not immediately included in any publication. A photograph shot by the studio of the Florentine Giuseppe Grazioli was deliberately excluded from Paul Fierens’s volume on the sculptor, published in 1936, and also from Lamberto Vitali’s, published in 1937 (the figure I am including is from the Scheiwiller Archive, whose publishing house curated the realization of the two small volumes).12The sculptor had insisted on the fragmentary condition of the terracotta, on the lack of expression in the woman’s face, and, most of all, on the modeling of an expressionless, archaic severity. The piece’s photographic reproduction – a classic three-quarter shot with light sources from the side and above – emphasizes the theme of the cone of shadow on the right, highlighting the plane of the face. The photograph gives us a luminous, timeless apparition, archaic but not auratic; and it voluntarily accentuates the contrast between the subject’s lack of expression and the expressionism of the material itself, whose smallest details are brought into focus.

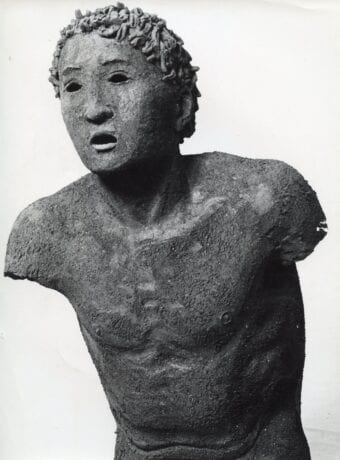

Manzù’s Testa di fanciullo (Head of Youth, 1932; figure 8), in multicolored cement and published in 1932 in the first short book dedicated to the sculptor, by Giovanni Scheiwiller,13 also falls in line with the project to overcome anatomical realism, but in this case via a more modern approach to deformation and stylization. The anonymous photographer intelligently selected a light background, from which the inverted pear-shaped mass of the head emerges; in the shot, the photographer also softened the interventions of working tool on the cement (meant to indicate hair, eyebrows, pupils) to draw a completely anti-sculptural texture on the surface. Anatomically disquieting compared to Marini’s Testa, Manzù’s Testa di fanciullo claims a relatively sentimental appearance, in which the artist’s touch takes center stage; the photograph points to how Manzù derived the deliberate inconsistency between the modeling and the treatment of the surface from Rodin’s later work.

As the years went by, the gap between Marini and Manzù widened. In Marini’s work, archaic references (which became, after a certain date, more Egyptian than Etruscan), shifted to an attention on geometric synthesis, with limited and elegant additions of color. Mario Perotti’s photographs of his Ritratto della signora Verga (Portrait of Mrs. Verga, 1936; figure 9) isolate the head as if it were a closed solid unto itself. For its reproduction in Fierens’s 1936 book, the shot was manually retouched, eliminating the base: the oval of the head appears surrounded by a light gray surface, painted directly over the photographic print and imbueing it with a sense of “timelessness.”14 A small wax head by Manzù from 1934 (figure 10) had received, again by Perotti, an opposite reading: the photograph underscores the meaning of the sculpture, resting on a concrete surface, as a precious and irreplaceable object; indeed, the photographer’s focus on the graphic interventions on the wax calls attention to the “here and now” of the artist who traced them.15

With full-figure sculptures, the issue for photographers was the type of aura with which an artwork ought to be charged. Whoever was looking at the photograph (ideally, the reader of a book or journal) had to understand the attitude with which the photographer approached the original, in order to be guided in its interpretation. Milanese photographer Egenio Petraroli’s image of Marini’s Giocoliere (Juggler, 1933; figure 11) treats the sculpture with the implacable objectivity usually reserved for Egyptian sculpture: the three-quarter shot outlines a sculpture suspended in time against a uniform background of accurately represented detail.16 It is impossible to confuse the sculpture with a body: the photograph’s subject is a statue, not a body. The viewer is prompted to read the statue’s formal balances, its synthesis of profile, and even an African, Egyptian character of the physiognomy (very distant from the Italic-Mediterranean racial typology, that becomes rampant in Italian sculpture after 1930).

It is not a minor point that, when Marini included a reproduction of this sculpture in the 1941 monograph of his work prefaced by de Pisis, he chose a different photograph (figure 12): a frontal one that can be attributed to the photographer Gianni Mari.17 The Egyptian allusion was reinforced here (traditionally, the photographic framing of Egyptian sculptures was either frontal or in profile), yet this innovative shot, with its grazing light, highlights the surface’s tormented matter, bringing attention to the hand that had modeled it; additionally, the hint of the artist’s studio as a backdrop encourages the reading of the sculpture as produced by a modern artist. It is not surprising that Giovanni Scheiwiller decided to cancel out the background on this photo’s negative for the monographs by Fierens, in 1936, and by Vitali, in 1937 (figure 13), instead setting the main figure against a uniform gray; the idea of Marini conveyed in these two monographs was that of an implacably purist plastic sculptor, and any insistence on the sculpture’s setting in the photographs evidently reduced the strength of this message.18

Scheiwiller’s previously cited short 1932 publication dedicated to Manzù included an unexpected illustration of Il Re (The King, 1931; figure 14); today lost, the statuette was an evident allusion to Italian bronzes of the pre-Roman era.19 It was difficult to photograph such a sculpture, as it stood on the cusp between archaism and modernist graphic styles (studied by Manzù also in his drawings of this period). The photographer, again anonymous, translated the subtle relationship between dainty corporality and museum-quality pretense with an unusual softness of chiaroscuro, in contrast with the shot’s absolute frontality. The undefined background provokes further feelings of disquietude in the observer; here there is no reference to the concrete backdrop of an artist studio. Lastly, another confusing element regarding the very status of the work is the signature: Manzù almost certainly did not sign the sculpture’s base, but rather the negative of the photograph of it. The choice of no setting in the photograph of Il Re is exceptional for Manzù, and during the following two decades, the sculptor always wanted his artworks photographed in relation with a physical space.

The photographic representation of any sculpture situated in the studio was crucial in the two sculptors’ media strategies. In fact, ambient photography focuses attention on the present time, or moment, of invention and execution, and this was particularly important for overtly archaistic sculptural styles. Even here, however, Marini’s and Manzù’s outcomes are at odds. Let us consider a telling case for Marini. When Giuseppe Grazioli was the first to photograph Popolo (People, 1929; figure 15), which Marini had just completed in his studio in Florence at via degli Artisti, he framed it in a three-quarter view, as was customary for full relief. The view highlights the motif of the man and woman’s outward-extended arms, and the shot includes other sculptures – well-defined heads and portraits that reinforce the perception of Popolo as a sculpture fully in the round. But this shot did not have much currency, and the frontal version, which treats the sculpture as a high-relief, took over. Unfortunately the quality of the rare frontal reproductions of this sculpture, documenting it before it was mutilated, does not allow an evaluation of the figures’ background: in Fierens’s book from 1937 and subsequent plates, the background is cropped close (figure 16) and substituted by a uniform gray background.20 However, after Marini mutilated the sculpture (by removing the two protracted arms), the background became an indispensable component of the relief: this is documented in a photo (figure 17) shot by Virginio Mazzucchelli, one of Marini’s students, in his studio at the Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche in Monza (hence, before 1941).21 This is not just any background: it is a wall coved with traces, fractures, and even drawings, perhaps by the artist himself. The balance we read in Popolo between references to an Etruscan cinerary urn and to contemporaneous rural life in Tuscany is enhanced by the physicality, the concreteness of that background wall. It is therefore not a surprise that, beginning with Carrieri’s monograph published by Milione in 1948,22 this became the official shot, although corrected in comparison with the original photo (the wall drawings, which evidently caused visual disturbance, had been elided).

Even in images of the opposite emotional declination, exemplified through Manzù’s affectionate and caricatured Portiere (Goalkeeper, 1932–33; figure 18),23 the background plays a decisive role. The empty, bare (and therefore magical) space of the studio is, in many of these, conceived to create an effective contrast with the meticulous graphic details readable on the work’s surface. This choice calls into play not only formal matters. The photograph directs the attention of the viewer to the sculpture’s particularly enchanted poetry, of an almost magical distance. The transformation of a goalkeeper – in jersey, kneepads, and soccer shoes – into a sculptural subject was already a stretch (one can think back to the sculptures of athletes being placed, in the same months, in the Stadio Mussolini, and to how those were photographed); its placement in a modern artist’s empty studio multiplies its antiheroic and pathetic content. During these years, photographers demonstrated great skill in using backgrounds as elements capable of directing the interpretation of a reproduced work.

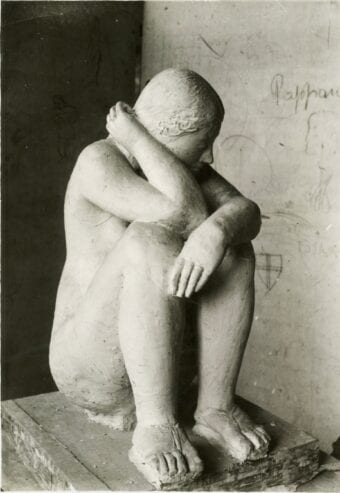

As photographed (perhaps again by Mazzucchelli) immediately after its transposition from clay to plaster, Marini’s Bagnante (Bather, 1934; figure 19)24 can easily be read as insistent on the material processes of its creation. The plaster’s details (and its modeling imperfections, based in freshly cast clay) call attention to these processes. The photographic reproduction of Bagnante shows it inside a school, the Istituto Superiore di Arti Applicate in Monza, where Marini taught, and on the wall the viewer can read scribbled writings by students (tags, mockeries, the coat of arms of the soccer team Ambrosiana Inter). In this environment, the teacher’s artwork served as a technical demonstration for his students. The same sculpture achieves an opposite effect once transposed into marble and purchased by the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, as captured in a photograph showing the opposite side in a slightly offset profile (figure 20). Here, the nude’s pure, closed form appears placed against a uniform, neutral backdrop.25

Let us take, from the same years, Manzù’s small bronze figures, photographed in the artist’s studio: Donna che si pettina, Figura piegata (figure 21), and Donna che piange.26 The photographic shots of these pathetic, aching figures, sometimes in poses of strange gestural eloquence, should be attributed to Attilio Bacci. They underscore that there is no fracture between the soft light illuminating the surfaces and the studio light; in other words, there is no distance between the sculpture and modern feelings and passions. If it is true that the bodies of Manzù’s figures unequivocally denounce their contemporary character (Luigi Bartolini would intelligently note, some years later: “In any of Manzù’s nudes one can understand the times in which the model lived”),27 photos like these equally insist on the human story that takes place within the studio.

4.

The theme of the relationship between sculpture and background is, as we have seen, central to the images produced by photographers of works by the artists Marini and Manzù – not only because of what a backdrop can tell (particular settings become precious keys to understanding the artist’s internal world), but also, and more importantly, for the plastic relation that is established between a sculpture and the environment in which it is contained.

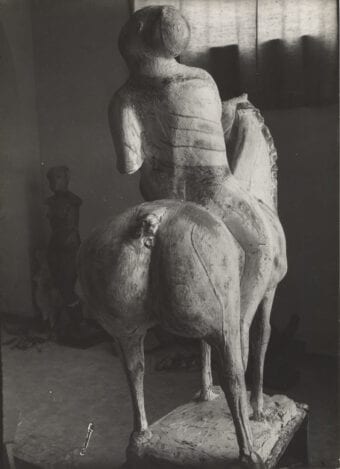

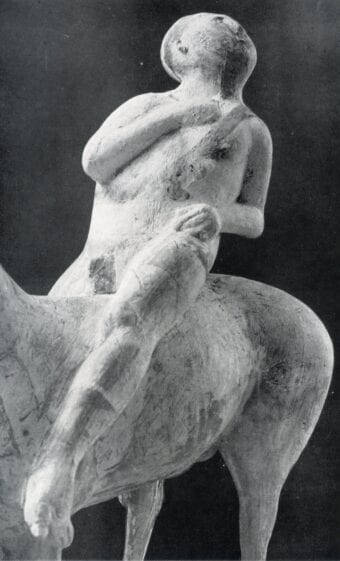

Yet, the crucial challenge in photographic reproduction takes place on another terrain: that of the point of view from which the sculpture is captured, the framing of the artwork, and the grouping and sequencing of the various shots upon publication. This issue gained particular importance when, after the first half of 1930s, both Marini and Manzù began to experiment in relation to working with live models, calling into question more directly the concept of three-dimensionality. Two important sculptures from the second half of the 1930s, decisive for the two artists’ fame, are Marini’s plaster Cavaliere (Rider),28 shown at the Venice Biennale in 1936, and Giacomo Manzù’s bronze David,29 exhibited at the Rome Quadriennale in 1939. Let us consider the photographs that made these sculptures known.

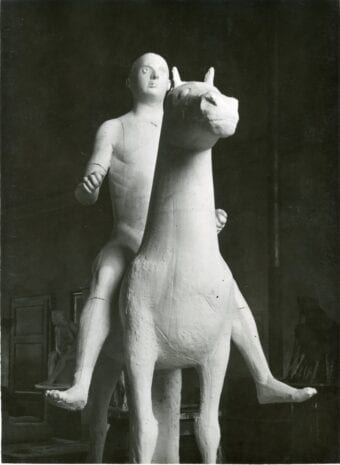

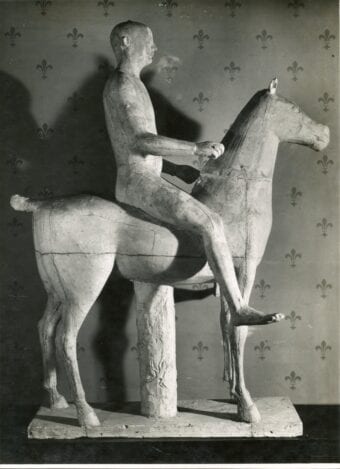

The Cavaliere represents a pivotal moment in Marini’s career: it was his first work to be severely censored (Ojetti would not forgive its “equestrian mamalucco” character),30 and the first to offer the archaic style (a cross between the equestrian statue of Marco Nonio Balbo at the Museo Nazionale di Napoli and the horseman at Bamberg’s cathedral) as an end in and of itself (without diversions such as a fragmentary state or a tormented surface). The large dimensions and the illustrious subject, a man on a horse, perhaps signaled Marini’s conversion to classicism. Instead, the sculptor radicalized his previous ideas of archaism and plastic abstraction; defending himself from the attacks by critics, he explained how the two principles guiding his oeuvre were “musical rhythm” and “geometric spirit.”31

There are two most notable photos of Cavaliere. The first, which was used for the press and in the catalogue of the Biennale,32 is a frontal shot (figure 22) and off-axis just enough not to hide the rider’s torso behind the horse’s neck and head. Most importantly, it was shot from below – an obvious choice for such a subject, therefore assimilating it among equestrian monuments, an obsolete sculptural typology. The lighting is dramatically artificial: a bright spotlight positioned low and to the right lifts the candid plaster mass against the studio’s darkness, where any other presence is rendered almost unreadable (the studio door, the stove chimney, and a lost version of Pugilatore in riposo [Resting Boxer] disappear in the background). Such photographic technique accentuates the volumes’ abstract purity. A similar reading was later adopted when the sculpture was photographed in its subsequent location, the house of Vittorio Barbaroux, where Gianni Mari sought to achieve the same effect by way of the shadow projected against the wall – as a monumental, almost metaphysical suspension.33

The second photo of Cavaliere is only in appearance an alternative to the first. This one is a profile of the sculptural ensemble placed against a wall covered with Medici lilies, at a location difficult to establish. The lighting here (similar to the first shot, from a source placed below and to the right) and the shooting angle seek different values. In fact, the relationship between the highly decorative motif of the background and the statue’s intricacies is emphasized – and this involves both the details which the sculptor sought out (the salamander on the plinth, the horse’s visible veins) and the minutiae that result from the mechanic transposition from clay to plaster (the visible joints between individual molds indeed create a graphic pattern that is different, in that it is rectilinear). Both reproductions of Cavaliere, however, insist on the same concept: the sculpture as an object in relation to a world of shapes (and perhaps a world of the artist’s private mythologies), but having nothing to do with contemporary times.

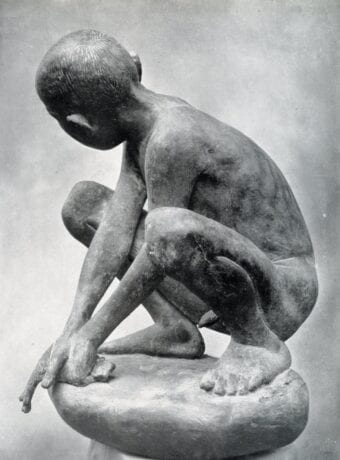

Two years later, Manzù modeled a David which relates, in the figure’s crouching pose, to a piece he had already realized of the same subject; the earlier sculpture had won the Premio Principe Umberto in Milan in 1936, but was stolen from his studio.34 The new David, in bronze, was shown at the Rome Quadriennale of 1939, and soon became considered a sort of manifesto-piece for the new values of humanity and spirituality that could be recognized in it – promoted by a series of photographs that exalted the peculiarity of its pose and modeling.

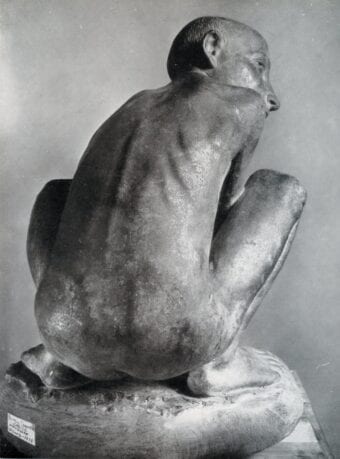

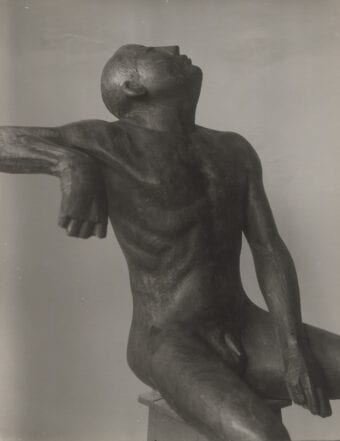

Let us consider the shots of the whole figure. The first, by Attilio Bacci, has a lateral point of view (figure 24); it focuses on the gesture of the boy as he picks up a stone, and it aims to attract the viewer’s attention to the logic of opposing movements. The photograph underscores the antimonumentality of the pose, its stupefying spontaneity, which contemporary critics called into question through an arc of references, from Hellenistic sculpture to Donatello and Vincenzo Gemito. This was not, however, the photograph chosen for the sculpture’s printed circulation. Mario Perotti’s shot from behind (figure 25) focuses on the figure’s back, which is curved and slightly twisted – this became the standard illustration of the piece.35 The photographer’s sensibility emphasized Manzù’s rendering of the sinking plastic planes around the left shoulder, allowing the ribs’ graphic motif to emerge; thus, he created a synthetic profile to highlight the refinement of the modeling.

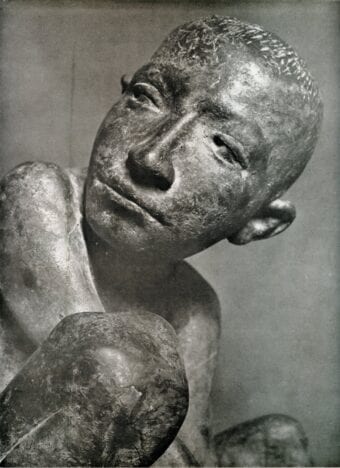

In neither of these photographs is the face put into relation with the figure. Instead, it is isolated by Attilio Bacci in a superb detail shot from below (figure 26), which includes even the knees and shoulders in the unusual compression of the crouched posture.36 The camera’s diaphragm, in this unusual case left open, facilitated an almost alienatingly detailed focus in its extreme close-up of the right knee and the face. Viewers of the photograph are compelled to think about the sculptor’s will regarding the meaning taken on by this particular modeling, which is indeed true to anatomy, but at the same time, almost abstract in appearance, as an application of “push” modeling (from the inside), which Arturo Martini had recently been experimenting with.37 Nonetheless, the viewer is driven to question the presence of casting imperfections that enrich the surface with arabesques and crinkles. The rest of the shot (left shoulder, knee, and ear) – blurred and out of focus – serves the same function as the studio’s faint presence in other photographs: it creates an atmosphere that puts different elements, physical but also emotional, into relation with each other.

It is worth noting that these shots were never reproduced alone, but rather in sequences in the realization of publications on the artist (a profile and detail of the face in Bertocchi’s 1943 book; a rear view and profile in Anna Pacchioni’s 1948 volume as well as in Carlo L. Ragghianti’s, published in 1957).38 Such sequences demonstrate an uninterrupted flow of profiles, calling attention to the continuous discovery of plastic motifs that a viewer would observe in walking around the bronze in real life.

Still, in 1938, as the first reproductions of Manzù’s David began to circulate, Domus published an article covering the Della Ragione collection, with a photograph of Marini’s bronze Piccolo pugile (Small Boxer, 1935).39 For this shot, the Genoese photographer Sciutto unequivocally asserted that the figure must not rotate in space: it required a single shot and a single light source, because only in this way are the relationships between profile and modeling (now completely autonomous with respect to the real nude) best expressed. In other photographs from the 1930s of the same sculpture, neither the point of view nor the lighting ever change. However, there is an interesting variety with regard to the cropping made on the same photograph in the typographical phase. Eloquent examples of this practice are the illustrations found in the books by Fierens, from 1936, and Vitali, from 1937.

For Marini’s Icaro (Icarus, 1933),40the photographer employed a slightly different take in isolating the torso motif and archaic arms;41 in Pugilatore (Boxer, 1935),42 a close-up on the torso (figure 27) that brutally cuts out portions of an arm and two legs nonetheless appears as a pure removal from the whole (figure 28).43 Marini’s sculpture does not seem to allow any freedom when it comes to points of view. Rather, the concentration on a specific portion places the emphasis on the iron-clad logic of the design presiding over the sculpture as a whole; a logic which remains convincing, and is indeed enhanced, when investigated in detail.

5.

Between the end of the 1930s and the years of the Second World War, the definitive consecration of the two sculptors on the Italian art scene was accomplished. Never as in this period are the reciprocal differences between the two artists interpreted by photography as two alternative paths for Italian sculpture. Let us start with Manzù.

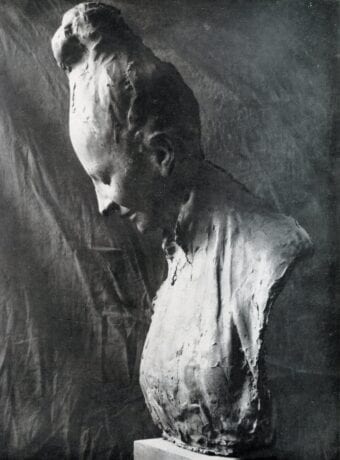

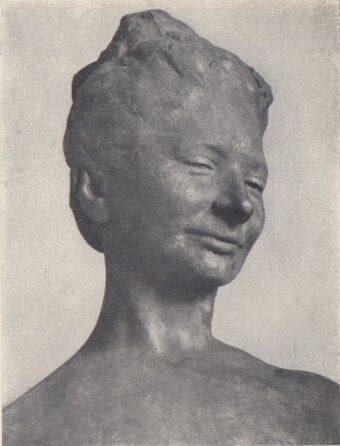

It is not surprising that, for the first important article dedicated to Manzù by the widely-known art history publication Emporium, his sculptural heads in bronze or wax were photographically reproduced in substantial number.44 With these heads – all portraits – Manzù established his personal challenge to the model of Medardo Rosso, as the photographs well document. These images, mostly by Attilio Bacci (who was positioning himself as the artist’s trusted photographer; figures 29–31), spread throughout Italian art periodicals between 1938 and 1940, declaring with conviction that the only point of view from which to capture a head was by capturing the relationship between volume and shadow to reveal the subject’s personality. The photographer determined the visual conditions needed to achieve the portrait’s maximum expressivity: the arrangement of the lights and the choice of the background plane. The latter could either be a studio setting, a sheet laid negligently behind the head, or an indeterminate backdrop.

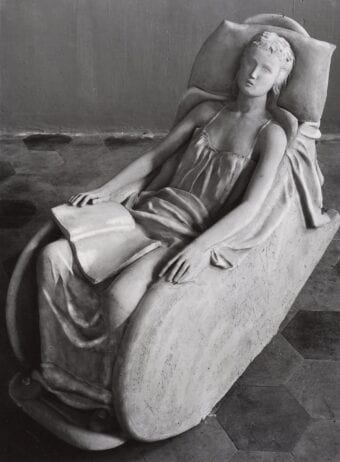

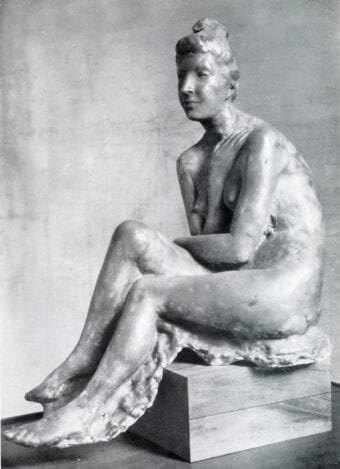

This principle was more or less respected even for full figures, and waxes and bronzes were read photographically as bas-reliefs, as one can see when considering the line that leads from the Susanna (1937; figure 32), to Donna che dorme (Sleeping Woman, 1938), to Francesca Blanc (1942; figure 33).45 In practice, only one point of view described the artist’s preferred visual themes: the outline of the legs, the intertwining of the arms, and the curve of the back. The slight variation in the angle of Francesca Blanc in the plates of Luigi Bartolini’s book does not enrich its interpretation at all, but rather creates a duplicate devoid of particular meaning.46

Only when the indeterminacy of the plastic planes inhibits the emergence of a guiding profile is the field left open to multiple shots. It seems that faced with Ritratto della Signora Vitali (1938–39; figures 34 and 35),47 the photographer (as well as the sculptor, at his side) was lost in uncertainty: for the reproduction to be published in a book by Beniamino Joppolo from 1946, uncertain about which to favor,48 Manzù delivered to Scheiwiller six photographs, of various points of view and widths of frame.

The work that represents the highest point of Manzù’s Leonardism did not allow the photographer a safe choice, as if the luminous vibrancy of the wax invited continuous slips of vision. Instead, when the stylistic reference is Donatello, as for Bustino di Bambina (Small Bust of Young Girl, 1940) or for Ritratto di Anna Musso (Mrs. Anna Musso, 1941), the plastic directives are openly declared, and thus the photographic points of view follow suit.49

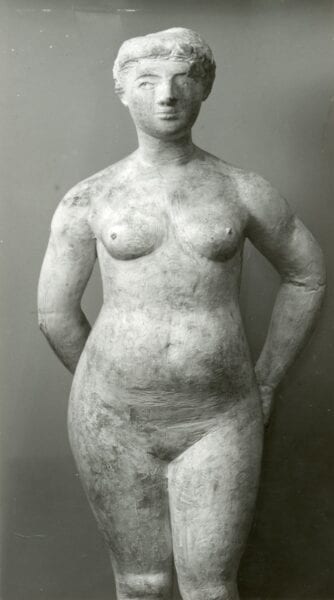

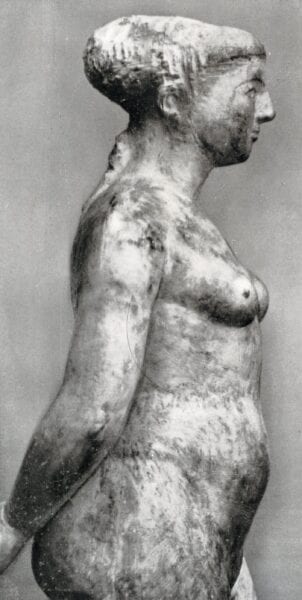

For Marini, the subject most interesting for photographers between the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s was the Pomona series. Obviously, to respect the artist’s intentions, the one way to interpret these sculptures photographically is to read the female body as an abstract form highlighting the relationships between volumes (figures 36 and 37). Photographers have often, most likely at the behest of the artist, resorted to cutting out some parts, as in a Pomona, with her arms behind her back, in the Jesi collection; this figure appears in a double shot by the photographer Perotti in the 1941 Marini monograph prefaced by Filippo de Pisis.50 Readers will notice two rigorous perspectives, the first frontal and the second in profile: these are the vantage points from which the pure volumes of the sculpture are most legible. Yet, the rich modeling of surfaces, which are not muted but rather breathing, opened a new challenge for the photographer, just as the attention Marini paid to sculpture after Rodin, from Aristide Maillol to Charles Despiau, struck a balance between archaic synthesis and the indication of a tangible, disquieting corporality.

6.

A separate chapter in the photographic fortune of the two sculptors covers the last tragic years of the war, when Marini lived in Tenero, near Locarno, from 1943 to 1945, and Manzù had relocated to Clusone, between 1943 and 1944 (the latter endeavoring in a season of research documented by the photographer Cristini, as we know from a footnote in Bartolini’s 1944 book). For both artists, one can richly discuss a photographic reinvention of contents in their respective sculptural trajectories.

Marini and Manzù responded to the tragedy of the last war years without backing away from their usual subjects (portraits and nudes for the former; portraits and religious themes for the latter). Nor did they betray their respective linguistic presuppositions. Something in their creative invention did change, however, and not in a minor fashion: their figures’ poses became more forced and dramatic, their physicality more suffering, and their surfaces more tormented.

The interpretations of the photographers called to document this production are symptomatic of these changes. The photographers seem to have preferred more angled vantage points, which might squash the figures against the floor or push them to stand out against uneven backgrounds, and they opted for more violent chiaroscuro effects, to underscore tortured processes.

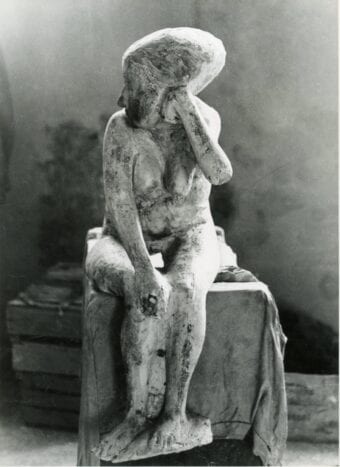

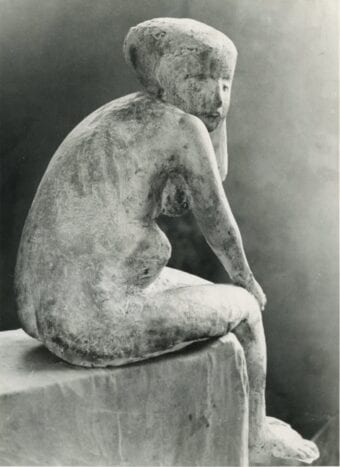

The photographer who captured Marini’s Susanna (1938–40) from three points of view (figures 38–40) no longer proclaimed the sculpture’s unassailable centrality.51 More than a solid, Susanna appears a fragile presence, whose nudity has been violated – a sort of wreckage, found and delicately placed on a case covered with a cloth. Other figures, or figure fragments, are placed on the ground, investigated with a pitiless gaze. A half-figure of a woman, exhibited at the Rome Quadriennale in 1943 and later known as Arcangela (1943; figures 41 and 42),52 was shot outside by a photographer whose eye implacably investigated her surface irregularities and the body’s mere status as casing (the internal void of the sculpture is perceptible through numerous fractures). The half-figure reads as potentially alluding to the devastating bombing of Italian cities. When Stile published one of these photos during the dramatic May of 1943, it was not silent about its contemporary implications: this figure, set in a courtyard strewn with rubble, seemed the symbol of “a more hardened youth, less defeated, more undaunted in bravely accepting its destinies but also in resisting them individually.”53

Manzù’s case is even more meaningful. After some disputes of iconographic orthodoxy generated by the exhibition of reliefs on the theme of the Crocifissione (Crucifixion) and Deposizione (Deposition) at Barbaroux Gallery in 1941, the sculptor experimented with a new direction in relief-making. Photographers interpreted this evolution with particular sensitivity. Attilio Bacci’s exceptional shots of Manzù’s reliefs exhibited at Barbaroux (figure 43) highlight, through strong grazing light, the expressive opportunities of a “stiacciato donatellesco.”54 Through the lenticular rendering of details, Bacci could also emphasize the continuous dialogue between the linear patterns etched on surfaces and parts that were softly modeled by pushing from behind. Only three years later, this way of reading a relief photographically was subverted. In a wax Autoritratto con Modella (Self-Portrait with Model, 1943; figure 44),55 where surfaces ripple as in Medardo Rosso’s lost great reliefs, the photographic rendering aptly shows the annulment of any distinction between the figures and the space surrounding them – the end result being the absence of profiles. We are not comparing a “private” draft with an ambitious series of representations of illustrious subjects. Manzù immediately attributed a fundamental role to Autoritratto con Modella; in a letter to Giovanni Scheiwiller from January 1945, written while a small volume on his work for the series “Artisti Italiani Moderni” was being prepared (published in 1946, with an introduction by Beniamino Joppolo), he recommended that “that small preparatory wax draft of Autoritratto con modella of 1943 not be missing.”56 It was indeed published with emphasis in the book, as well as in many later monographs.57

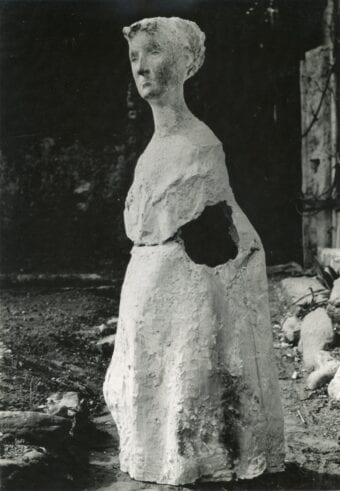

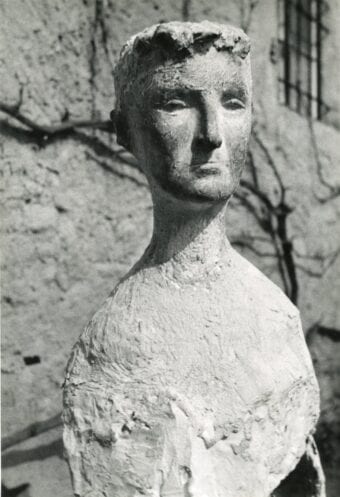

Manzù considered decisive, in terms of his self-representation in the last years of the war, the preparatory statuettes of major pieces in which freedom of touch, freshness of invention, and dramatic attitudes were exalted. The most evident examples are the preparatory sketches for the Motta tomb in the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano (figures 45–46), acclaimed in the postwar iconography of Manzù; indeed, one of these was illustrated as a full-page plate in the exhibition catalogue of the Milanese show at Palazzo Reale in 1947.58 These are bronzes obtained from perfunctory waxes, and for them Manzù retraced the history of modern figurative sculpture from Rodin to Degas and Martini (with precise allusions to the Giudizio di Salomone [The Judgment of Solomon, 1935] and to Famiglia di acrobati [Family of Acrobats, 1937]). Likely at the sculptor’s recommendation, the photographer pursued the status of the fragile and uncertain human condition expressed by these sculptures by producing images of the heroes of sacred history reduced to corroded and tormented figures standing out against a floral wallpaper more reminiscent of a domestic setting than an artist’s studio.

It is interesting to note how, within this period’s overall return to Rodin by both Marini and Manzù, even the photographers revisited – perhaps unknowingly – the dramatic points of view and contrasts applied in reproductions of the French sculptor’s late plaster and bronze fragments.

7.

If one artwork sums up Marino Marini’s research in the years immediately after the war, it is his Cavallo e Cavaliere (Horse and rider) of 1947, acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which the rider turns, as if struck by a vision from above – a gesture that the horse’s head seems to second. Two variations exist of this work: one in plaster with several polychrome interventions, in which the rider rests his left arm on his own leg (it is not included in the artist’s most recent general catalogue);59 another in bronze, in which the same arm is brought behind the back, creating leverage on the horse and thus accentuating the motif of the figure’s torsion.60 We can start by analyzing three shots of the plaster version from when it was still in the artist’s studio (in the background additional sculptures can be made out); these are published in the 1948 Marini monograph produced by Edizioni del Milione, with an introduction by Raffaele Carrieri.61 The presented sequence reveals, without a doubt, references to Cubism: a profile, with the replicated twisting gesture of both horse and horseman; a view from behind (figure 47), with a compression almost on the same plane of the horse’s and rider’s legs, and of the rider’s back and head; and a three-quarter view (figure 48), with a powerful close-up and violent lighting that washes out and expands the picture plane with an evident forcing of perspectives. Without decomposing the figure or applying interventions to compromise its legibility, Marini worked in accordance with Pablo Picasso’s devices, and the photographer followed suit. The figure did not have to rotate in front of the spectator’s eyes; it could rather be positioned in space via separate shots, and the picture planes could likewise almost collapse on top of one other. The artist’s chromatic interventions on the sculpture’s surface, always a bit dissonant with respect to its plastic syntax, have the same function that black lines have in Cubist paintings: they are distinct from the profiles of different masses, and therefore generated spatial ambiguities. The photographer’s choice is evident: the almost unifrom gray and low contrast give an account of the surface’s variety, softening its harshness and insisting on the strange patina (similar to that of ancient Chinese sculpture) that seems to envelop the artwork.

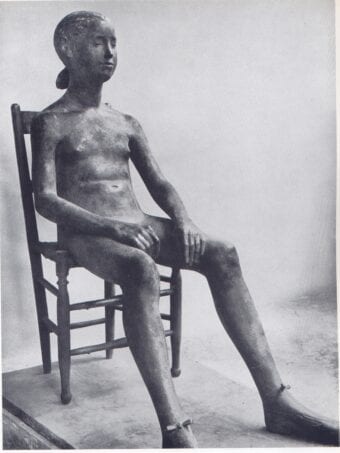

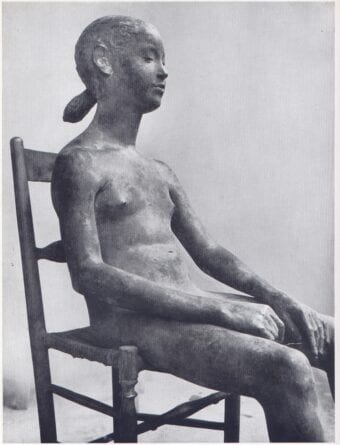

A comparison with Manzù’s most popular sculpture of the early postwar years, Bambina sulla sedia (Young Girl on a Chair, 1947), is instructive.62 The literal cast of an everyday object, a straw chair, hosts a delicate naked body, characterized by a breathing physicality and caught in an act not of abandonment but of self-collected concentration (as indicated, it seems, by the closed eyes). Manzù’s endeavor with this sculpture recalls the aspiration among nineteenth-century artists to make the most innermost spiritual component of a statue coexist with the most prosaic and realistic of details.

The most well-known photograph of this sculpture, taken by Attilio Bacci (figure 49), is set in an interior that should be the studio; but the crude contrast between the somber tone of the lead with which it was cast and the almost solarized surfaces of the back wall and floor negate this perception. What has emerged from the photographer’s lens is an object closed in on itself, devoid of a relationship with the space that contains it. What the photographer seeks out instead is the unusual richness of the surface drawing. Another photo (figure 50) brings the figure closer, refining this reading: it highlights the peculiar quality of the modeling, its disturbing mimesis of reality, and, at the same time, its design synthesis, which recalls a purist tradition. The slight rotation of the sculpture chosen for this second shot enhances the contrast between the dry profile of the chair and the breathing elasticity of the body.

After 1948, the photographic reproduction of the artworks by the two artists underwent a few more oscillations. Manzù’s sculpture would be the subject of photographs endorsing a particular profile, frequently emphasizing the work’s standing out against an indeterminate gray or black background – that is, the opposite of what had happened in depictions of his work in the 1930s. Such photos aimed to underscore a technical choice that became one of Manzù’s trademarks: a linear arabesque that overlaps, incoherently, with the modeling. It is an arabesque determined from even the lightest touch of the hand, from cracks and other casting imperfections, highlighted relentlessly by the focused insistence of the camera on a bronze surface. Such a photographic reading, in the end, interprets the three-dimensional work as a bas-relief.

For Marini’s work, photography acted in the opposite direction. Through the adoption of an intermediate photographic focus, the turbulent matter of the sculptural surface was consistently put in relation with the modeled mass (and, later on, with the bodies’ plastic structure). Its an invitation for the spectator’s eye to oscillate between volumes and surface details (rich in manual interventions by the artist, even when the bronze had already come out of the foundry). What results is a totally abstract wholeness, through which photographers investigated the perfect (and sometimes almost too elegant) correspondence between the work’s minimal chiaroscuro incidents and its general design.

On closer inspection, the photographers’ interpretation of these artists’ works aligns with the best critical readings of time. According to Umbro Apollonio, writing in 1953, Marini conveyed a “primordial poetry to which our culture was becoming unaccustomed,” generated by a perfect correspondence between “the robustness of mass and the surface’s quivering of patterning.”63 As for Manzù, Carlo L. Ragghianti, in 1957, described how we witness the development of a “Verdian” melody: “form, with its pulsed and marked beat, expresses the consistency, the truth of this cosmos, in such a way that humanity recognizes itself in it.”64

Bibliography

XX Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Catalogo. Venice: Ferrari, 1936.

Abadal, Daniele A. and Alberto Montrasio, eds. Marino Marini. Gli archetipi. Gemonio: Museo civico Floriano Bodini; Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Adolfo Wildt. Milan and Rome: Bestetti and Tumminelli, undated [1926].

Anonymous [Gio Ponti], “Umanità in tre opere di Marino alla Quadriennale.” Stile (May 1943).

Apollonio, Umbro. Marino Marini scultore. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1953.

Appella, Giuseppe, ed. Il carteggio Belli–Feroldi 1933–1942. Milan: Skira, 2003.

Bajac, Quentin, Clément Chéroux, and Philippe-Alain Michaud, eds. Brancusi, film, photographie. Images sans fin. Cherbourg-Octeville: Le Point du Jour, 2011.

Bartolini, Luigi. Manzù. Rovereto: Edizioni Delfino, 1944.

Bergstein, Mary. “‘(Un)richtige Aufnahme’: Sculpture, Photography and the Visual Historiography of Art History.” Art History, no. 36 (2013).

Bergstein, Mary. “Lonely Aphrodites: On the Documentary Photography of Sculpture.” Art Bulletin, no. 74 (September 1992).

Bertocchi, Nino. “Manzù.” Domus, no. 178 (October 1942): 447.

Bertocchi, Nino. Manzù. Milan: Domus, 1943.

Bignami, Silvia. “‘Lavoro che mi sta a cuore, perché va in piazza.’ Arte pubblica e concorsi a Milano negli anni Trenta del Novecento.” In L’arte pubblica nello spazio urbano. Committenti, artisti, fruitori, edited by Carlo Birrozzi and Marina Pugliese. Milan: Bruno Mondadori, 2007.

Billeter, Erika, ed. Skulptur im Licht der Fotografie. Von Bayard bis Mapplethorpe. Bern: Benteli, 1997.

Candido Grassi, Giacomo Manzù, Giuseppe Occhetti, Gino Pancheri, Aligi Sassu, Nino Strada. Milan: Anonima Editrice d’Arte, undated [1930].

Carrieri, Raffaele. Marino Marini scultore. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1948.

Cladel, Judith. Auguste Rodin. L’Oeuvre et l’Homme. Brussels: Van Oest & Cie, 1908.

Contini, Gianfranco. 20 sculture di Marino Marini. Lugano: Collana, 1944.

de Pisis, Filippo. Marino. Milan: Edizioni della Conchiglia, 1941.

Del Massa, Aniceto. “Giacomo Manzù.” Arte Mediterranea 1, no. 2 (March–April 1939).

Elsen, Albert Edward. In Rodin’s Studio: A Photographic Record of Sculpture in the Making. Oxford: Phaidon; Paris: Musée Rodin, 1980.

Fabi, Chiara. “Catalogo ragionato della scultura: 1929–1942,” in Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, doctoral thesis, Università degli Studi di Udine. Dipartimento di Storia e Tutela dei Beni Culturali. Dottorato di Ricerca. 13 ciclo, a.a. 2010–11, advised by Professor F. Fergonzi.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Arturo Martini. Un ventennio di sfortuna postuma,” in Per Ofelia, Studi su Arturo Martini, edited by Matteo Ceriana and Claudia Gian-Ferrari. Milan: Skira, 2010.

Ferretti, Massimo. “Fra traduzione e riduzione. La fotografia dell’arte come oggetto e come modello.” In Gli Alinari fotografi a Firenze. 1852–1920, edited by Wladimiro Settimelli and Filippo Zevi. Florence: Alinari, 1977. Exhibition catalogue.

Fierens, Paul. Marino Marini. Paris: Chronique du Jour; Milan: Hoepli, 1936.

Francini, Alberto. “Roma. Le mostre d’arte nei primi sei mesi di quest’anno – Le mostre collettive – Le mostre dei pensionati francesi, ungheresi e americani – A ‘La cometa’ – Alle altre gallerie, sale e salette.” Emporium 84, no. 501 (September 1936): 163.

Frizot, Michel and Dominique Paini, eds. Sculpter-photographier. Photographie-sculpture. Paris: Marval, 1991.

Ginex, Giovanna. “‘Contro la fotografia.’ La fotografia nella vita, nell’opera e nel pensiero critico di Boccioni.” L’Uomo nero, no. 9 (2012): 62–85.

Giolli, Raffaello. “Fermezza di Marino.” Domus (February 1943): 80.

Giovedì 18 marzo XV alle ore 17 s’inaugura alla Galleria della Cometa un’esposizione di Giacomo Manzù, Galleria della Cometa, March–April 1937.

Gruppo “L’Altana.” Mostra di Manzù. Introduction by Lionello Venturi. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1947. Exhibition catalogue.

Johnson, Geraldine A. “All concrete shapes dissolve in light: photographing sculpture from Rodin to Brancusi.” The Sculpture Journal, no. 15 (2006): 199–222.

Johnson, Geraldine A. ed. Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Johnson, Geraldine A., ed. The Very Impress of the Object: Photographing Sculpture from Fox Talbot to the Present Day. Leeds: Henry Moore Institute 1995.

Joppolo, Beniamino. Giacomo Manzù. Milan: Hoepli, 1946.

Le grandi raccolte d’arte contemporanea. La Raccolta Feroldi. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1942.

Leonardo Bistolfi. Milan-Rome: Bestetti and Tumminelli, undated [1911].

Manzù. With text by Giovanni Scheiwiller. Milan: Tipografia L’Eclettica, 1932.

Marchiori, Giuseppe. “Caratteri e forme della scultura italiana alla XXI Biennale di Venezia.” Corriere Padano, July 15, 1938.

Marini, Marino. “Spiegazioni.” L’Ambrosiano, May 25, 1938.

Marino Marini, with text by Eduard Hüttinger. Zürich: Kunsthaus Zürich, 1962.

Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura. Introduction by Giovanni Carandente. Milan: Skira, 1998.

Mason, Rainer Michael and Hélène Pinet, eds. Pygmalion photographe. La sculpture devant la camera, 1844–1936. Geneva: Musee d’Art et d’Histoire, 1985.

Messina, Maria Grazia. “Un’illustrazione di ‘Emporium,’ 1922 e fotografia della ‘scultura negra’ intorno al secondo decennio del Novecento.” In Emporium II. Parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964, edited by Giorgio Bacci and Miriam Fileti Mazza. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2014: 431–52.

Mola, Paola. Rosso. Trasferimenti. Milan: Skira, 2006.

Ojetti, Ugo. “La XX Biennale veneziana. Scultori nostri.” Corriere della Sera, July 5, 1936.

Ojetti, Ugo. “Lo scultore Libero Andreotti.” Dedalo 1, no. 2 (1920–21): 396–416.

Ojetti, Ugo. “Lo scultore Antonio Maraini.” Dedalo 1, no. 3 (1920–21): 743–58.

Pacchioni, Anna. Giacomo Manzù. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1948.

Padovani, Maria Donata. “Mario Perotti. Uno studio fotografico in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele a Milano.” Rassegna di Studi e Notizie, no. 29 (2005): 181–205.

Pinet, Hélène, ed. Rodin sculpteur et les photographes de son temps. Paris: Sers, 1985.

Ponti, Gio. “L’arte di Marino è stile,” Stile (May 1942): 37.

Popolo d’Italia, November 10, 1932.

Ragghianti, Carlo L. Giacomo Manzù scultore. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1957.

Scopinich, Ermanno Federico, Alfredo Orsano, and Albe Steiner. Fotografia. Prima rassegna dell’attività fotografica in Italia. Milan: Domus 1943.

Thovez, Enrico. “L’evoluzione di un romantico,” La Stampa, January 29, 1911.

Torriano, Piero. “Aspetti della moderna arte italiana. Lombardi e toscani,” L’Illustrazione Italiana (February 10, 1929): 194.

Venturi, Lionello. “Arturo Martini,” in L’Arte, 1, no. 6 (November 1930): 556–77.

Vitali, Lamberto. “Contemporary Sculptors. VII. Marino Marini.” Horizon, no. 105 (September 1948): 204.

Vitali, Lamberto. “Lo scultore Giacomo Manzù.” Emporium 87, no. 521 (May 1938): 246.

Vitali, Lamberto. Marini. Florence: Edizioni U, 1946.

Vitali, Lamberto. Marino Marini. Milan: Hoepli, 1937.

Wölfflin, Heinrich. “Wie man Skuplturen aufnehmen soll.” Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, vol. 7 (1896), 224–28, vol. 8 (1897), 294–97, vol. 26 (1915), 237–44.

- On the critical and commercial misfortune of Arturo Martini after 1945, I refer the reader to my “Arturo Martini. Un ventennio di sfortuna postuma,” in Per Ofelia, Studi su Arturo Martini, ed. by Matteo Ceriana and Claudia Gian-Ferrari (Milan: Skira 2010), 55–77.

- In letters to Carol Belli, Pietro Feroldi expressed that he was tormented by the true-to-life quality of the trichromes by the publisher Esperia. See Il carteggio Belli–Feroldi 1933–1942, ed. G. Appella, Documenti del MART no.7 (Milan: Skira 2003). This was occasioned not only by the preparation of the catalogue Le grandi raccolte d’arte contemporanea. La Raccolta Feroldi (Milan: Edizioni del Milione 1942) but already earlier, when, starting in 1938, some color plates of the paintings in Feroldi’s collection were printed and sold separately by the Galleria del Milione.

- The question of the relationship between photography and sculpture today boasts a vast specific bibliography, starting with the fundamental (and often cited) H. Wölfflin, “Wie man Skuplturen aufnehmen soll,” Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, vol. 7 (1896), 224–28, vol. 8 (1897), 294–97, vol. 26 (1915), 237–44 (under the subtitle “Probleme der italienischen Renaissance”). An Italian translation of the three articles is available in Fotografare la scultura, ed. B. Cestelli Guidi with the contribution of E. Delogu and a bibliography (Mantova: Tre Lune, 2008). The state of the studies is summarized, for sculpture before 1900, in the proceedings of the conference Sculpter-photographier. Photographie-sculpture, ed. M. Frizot and D. Paini (Paris: Marval, 1991); and for late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century sculpture, in the proceedings of the conference Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension, ed. G. A. Johnson (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998), see especially the curator’s introduction. By the same scholar there is an opening on the dematerialization of the formal content of sculpture through photography in “All concrete shapes dissolve in light: photographing sculpture from Rodin to Brancusi,” The Sculpture Journal, no. 15 (2006): 199–222. Regarding professional sculpture photography, see M. Bergstein, “Lonely Aphrodites: On the Documentary Photography of Sculpture,” Art Bulletin, no. 74 (September 1992), 475–98; and “‘(Un)richtige Aufnahme’: Sculpture, Photography and the Visual Historiography of Art History,” Art History, no. 36 (2013): 12–51. However, M. Ferretti’s “Fra traduzione e riduzione. La fotografia dell’arte come oggetto e come modello,” in the exhibition catalogue Gli Alinari fotografi a Firenze. 1852–1920 (ed. W. Settimelli and F. Zevi; Florence: Alinari 1977) remains indispensable on the question of how a professional photography studio approaches artistic artifacts with the eye and culture of its own time. Some exhibitions (and their catalogues) have questioned the theme of the relationship between photography and sculpture, including Pygmalion photographe. La sculpture devant la camera, 1844–1936, ed. R. M. Mason, H. Pinet (Geneva: Musee d’Art et d’Histoire, 1985); The Very Impress of the Object: Photographing Sculpture from Fox Talbot to the Present Day, ed. G. A. Johnson (Leeds: Henry Moore Institute 1995); Skulptur im Licht der Fotografie. Von Bayard bis Mapplethorpe, ed. E. Billeter (Bern: Benteli, 1997). Particular attention has been paid by scholars to the photographs of the sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Medardo Rosso, and Constantin Brancusi, three artists who have made the photography of their work a powerful interpretive key as well as an irreplaceable tool for self-promotion. On Rodin, see A. Elsen, In Rodin’s Studio: A Photographic Record of Sculpture in the Making (Oxford: Phaidon; Paris: Musée Rodin, 1980); Rodin sculpteur et les photographes de son temps, ed. H. Pinet (Paris: Sers, 1985). On Rosso, see P. Mola, Rosso. Trasferimenti (Milan: Skira, 2006). On Brancusi, see Brancusi, film, photographie. Images sans fin, ed. Quentin Bajac, Clément Chéroux, and Philippe-Alain Michaud (Cherbourg-Octeville: Le Point du Jour, 2011). Interesting, too, is the analysis of the photographs of the sculptor Boccioni in G. Ginex, “‘Contro la fotografia.’ La fotografia nella vita, nell’opera e nel pensiero critico di Boccioni,” L’Uomo nero, no. 9 (2012): 62–85. An excellent reflection on the linguistic revolution posed and the theme of photographing tribal objects is in M. G. Messina, “Un’illustrazione di ‘Emporium,’ 1922 e fotografia della ‘scultura negra’ intorno al secondo decennio del Novecento,” in Emporium II. Parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964, ed. G. Bacci and M. Fileti Mazza (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2014), 431–52, with a rich bibliography.

- Bertocchi, Nino. Manzù. Milan: Domus, 1943, introduction.

- Lionello Venturi, “Arturo Martini,” in L’Arte, 1, no. 6 (November 1930): 556–77.

- Leonardo Bistolfi (Milan-Rome: Bestetti and Tumminelli, undated [1911]). The photographer or photographers of the plates are not mentioned in the book’s colophon, nor in E. Thovez’s review of it, “L’evoluzione di un romantico,” La Stampa, January 29, 1911.

- Judith Cladel, Auguste Rodin. L’Oeuvre et l’Homme (Brussels: Van Oest & Cie, 1908).

- Adolfo Wildt (Milan and Rome: Bestetti and Tumminelli, undated [1926]).

- Ugo Ojetti, “Lo scultore Libero Andreotti,” Dedalo 1, no. 2 (1920–21): 396–416: and “Lo scultore Antonio Maraini,” Dedalo 1, no. 3 (1920–21): 743–58.

- The reproduction was published in P. Torriano, “Aspetti della moderna arte italiana. Lombardi e toscani,” L’Illustrazione Italiana (February 10, 1929): 194.

- The reproduction is published in the catalogue of an exhibition on view at Galleria Milano from April 1–13, 1930: Candido Grassi, Giacomo Manzù, Giuseppe Occhetti, Gino Pancheri, Aligi Sassu, Nino Strada (Milan: Anonima Editrice d’Arte, undated [1930]), unpaginated.

- It is the Testa catalogued in Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato, no. 67; it does not appear in Paul Fierens, Marino Marini (Paris: Chronique du Jour; Milan: Hoepli 1936) nor in Lamberto Vitali, Marino Marini (Milan: Hoepli, 1937).

- Manzù, with text by Giovanni Scheiwiller (Milan: Tipografia L’Eclettica, 1932), fig. II. There is no printed general catalogue of Manzù’s sculpture. For the first portion of his activity, one must refer to the appendix “Catalogo ragionato della scultura: 1929–1942,” in Chiara Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, doctoral thesis, Università degli Studi di Udine. Dipartimento di Storia e Tutela dei Beni Culturali. Dottorato di Ricerca. 13 ciclo, a.a. 2010–11, advised by Professor F. Fergonzi. The piece, in cement, is lost; it is dated 1931 and no. 8 in ibid.

- The colorful terracotta head from 1937 is no. 128 in Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, with introductory text by G. Carandente (Milan: Skira, 1998). It is reproduced against a silver-gray backdrop in Fierens, Marino Marini, fig. 15; against a black background that noticeably changes the sculpture’s chiaroscuro values in Vitali, Marino Marini, fig. 28; and again on a silver-gray background in Marino, presented by Filippo de Pisis (Milan: Edizioni della Conchiglia, 1941), fig. 16. In the photographic print preserved at the Scheiwiller Archive, the manual intervention that eliminated the base is clearly visible; on the print’s verso, the Studio Fotografico Abeni of Mario Perotti left a stamp (Milan, Galleria Vittorio Emanuele 2). For detailed research on Mario Perotti’s activity in Milan from 1909–99 and on the photography studio Abeni, see M. D. Padovani, “Mario Perotti. Uno studio fotografico in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele a Milano,” Rassegna di Studi e Notizie, no. 29 (2005): 181–205.

- It is the Studio per una testa di cantante (Study for Head of a Singer, 1934), in Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, no. 40. In the reproduction in A. Francini, “Roma. Le mostre d’arte nei primi sei mesi di quest’anno – Le mostre collettive – Le mostre dei pensionati francesi, ungheresi e americani – A ‘La cometa’ – Alle altre gallerie, sale e salette,” (Emporium 84, no. 501 [September 1936]: 163), the base on which the head rested is elided.

- This sculpture is in Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato, no. 86. The print is in the Scheiwiller Archive in Milan; the stamp its back reads “Eugenio Petraroli fotografo. Lavori industriali-Riproduzioni di opere d’arte. Via Settembrini 123, Milano.” Petraroli was also an independent photographer: two of his shots with naturalistic subjects (Martin pescatore [Kingfisher] and La Belva [The Beast], both undated) are reproduced in F. Scopinich with A. Orsano and A. Steiner, Fotografia. Prima rassegna dell’attività fotografica in Italia (Milan: Domus 1943), 37 and 161.

- De Pisis, Marino, fig. 46. Gianni Mari’s photography for the book is credited, as mentioned, in the colophon.

- Fierens, Marino Marini, fig. 2; Vitali, Marino Marini, fig. 9.

- Manzù, with text by G. Scheiwiller, fig. 3; Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, no. 9.

- For the Popolo of 1929 (Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato, no. 86) there are three different documented states. The original and intact one is illustrated for the first time in Popolo d’Italia, November 10, 1932; the second, in which the man’s right forearm and the woman’s right forearm are mutilated, is documented in photographs by Virginio Mazzucchelli taken in Marini’s studio at ISIA in Monza, and therefore dateable to before 1942, when the sculptor took service at the Accademia di Brera; the third, in which the man’s right arm is entirely mutilated, as well as a small portion of the left side of the woman’s torso, is illustrated for the first time in the exhibition catalogue Marino Marini (Zürich: Kunsthaus Zürich, 1962), with text by Eduard Hüttinger, no. 1. In its first condition, the sculpture was published – cropped against a neutral backdrop – in Fierens, Marino Marini, no.3, and then again in R. Giolli, “Fermezza di Marino,” Domus (February 1943): 80 (in all likelihood, the sculpture had already been mutilated by that date).

- Mazzucchelli’s shots are published in the exhibition catalogue Marino Marini. Gli archetipi, ed. D. A. Abadal and Alberto Montrasio (Gemonio: Museo civico Floriano Bodini; Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2008), unpaginated.

- Raffaele Carrieri, Marino Marini scultore (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1948), fig. 2.

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, no. 23.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato, no. 98.

- For instance in Fierens, Marino Marini, fig. 19; Vitali, Marino Marini, tav. 18.

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, nos. 45, 50, and 66. Donna che si pettina (exhibited with the title Adolescente at the Biennale of 1936) was photographed by Mario Perotti in the artist’s studio; on the occasion of its first publication (Lamberto Vitali, “Lo scultore Giacomo Manzù,” Emporium 87, no. 521 [May 1938]: 246) the bronze was cropped of its background, in line with the magazine’s editorial habits. The same thing happened for Uomo piegato (G. Marchiori, “Caratteri e forme della scultura italiana alla XXI Biennale di Venezia,” Corriere Padano, July 15, 1938), whose first reproduction with the original background was used in Anna Pacchioni, Giacomo Manzù (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1948), fig. 9. Even for the leaflet of Manzù’s solo show at Galleria della Cometa in Rome (Giovedì 18 marzo XV alle ore 17 s’inaugura alla Galleria della Cometa un’esposizione di Giacomo Manzù, Galleria della Cometa, March–April 1937) the shot is deprived not of the sculpture’s base, but of the large drape that, on the left, covers another sculpture.

- Luigi Bartolini, Manzù (Rovereto: Edizioni Delfino, 1944), 12

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato, no. 115. The bronze version, already belonging to the Jesi collection, is the one that is catalogued; the plaster cast shown at the Biennale was destroyed.

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, no. 88.

- Ugo Ojetti, “La XX Biennale veneziana. Scultori nostri,” Corriere della Sera, July 5, 1936.

- M. Marini, “Spiegazioni,” L’Ambrosiano, May 25, 1938.

- XX Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Catalogo (Venice: Ferrari, 1936), fig. 16; in Fierens, Marino Marini, fig. 38, the background appears black and the rider’s left leg is cut off.

- G. Ponti, “L’arte di Marino è stile,” Stile (May 1942): 37.

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, no. 49. Two views of this first Davide (one from behind; another a detail of the face) were reproduced in the magazine Il Frontespizio in May 1937 (figures 3 and 5).

- Starting with the first publication in Vitali, “Lo scultore Giacomo Manzù,” 245. An alternative to this shot, a view from the back, was published in A. Del Massa, “Giacomo Manzù,” Arte Mediterranea 1, no. 2 (March–April 1939), 45. It is rotated by 45 degrees to the left and insists on the motif of the virtuoso graft of the folded leg on the trunk; this reproduction was not used in later publications.

- Published for the first time in Nino Bertocchi, “Manzù,” Domus, no. 178 (October 1942): 447.

- This was an experimental attempt to apply a repoussé technique to three-dimensional clay models.

- Nino Bertocchi, Manzù (Milan: Domus, 1943), figs. 16 and 17; Pacchioni, Giacomo Manzù, figs. 16 and 17; Carlo L. Ragghianti, Giacomo Manzù scultore (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1957), figs. 14 and 15.

- Marino Marini. Catalogue raisonnèe, no. 117.

- Ibid., no. 87.

- Fierens, Marino Marini, figures 27 and 28; Vitali, Marino Marini, figures 10 and 11.

- Marino Marini. Catalogue raisonnèe, no. 102.

- Fierens, Marino Marini, figures 30 and 31; Vitali, Marino Marini, figures 20 and 21.

- Vitali, “Lo scultore Giacomo Manzù,” 245 (Testina [Small Head]), 247 (Testa femminile [Female Head]), 249 (Maschera bianca e Ritratto della moglie, [White Mask and The Artist’s Wife], 1937 and 1934), 250 (Ritratto della moglie [The Artist’s Wife], 1934), and 251–52 (Donna col cappello [Woman with Hat], 1937).

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, respectively nos. 75, 81, and 139. In Susanna the same point of view is retained in two photos characterized by a very different lighting of the piece: the first shot, by an anonymous photographer, is the one published in Vitali’s “Lo scultore Giacomo Manzù” (page 253), which later imposed itself as the official photograph; the second is the one probably shot by Gianni Mari, in Bertocchi, Manzù, fig. 11. The framing angle is identical even in the interesting photo of the wax version of the sculpture placed in the artist studio and published in A. Del Massa, “Giacomo Manzù,” Arte Mediterranea 1, no. 2 (March–April 1939): 42.

- Bartolini, Manzù, figs. 11 and 13.

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, no. 95. The first reproduction known to me is the left profile photographed by Attilio Bacci in Bertocchi, Manzù, fig. 19.

- The same profile that appears in Bertocchi’s book, and a detail of the face framed in a three-quarter view, were published in Beniamino Joppolo, Giacomo Manzù (Milan: Hoepli, 1946).

- Fabi, Gli anni Trenta nella scultura di Giacomo Manzù, nos. 115 and 133. The two bronzes, exhibited at the Rome Quadriennale in 1943, were reproduced from two different points of view in Bartolini, Manzù: figs. 15 and 17 (with the addition of a close-up of the profile, fig. 19), for Anna Musso; and figs. 25–27, for the Busto di bambina.

- Marino Marini. Catalogue raisonné, no. 165.

- Ibid., no. 196. The crucial role of these shots is confirmed by their circulation starting with G. Contini, 20 sculture di Marino Marini (Lugano: Collana, 1944), figures 2–3; and, after the war, beginning with Lamberto Vitali, Marini (Florence: Edizioni U, 1946), fig. 23.

- Marino Marini. Catalogue raisonné, no. 187.

- Anonymous [G. Ponti], “Umanità in tre opere di Marino alla Quadriennale,” Stile, no.29 (May 1943): 52.

- A relief technique that allows the representation of great depth and perspective.

- Ragghianti, Giacomo Manzù scultore, 68.

- Milan, Centro Apice, Scheiwiller Archive, Carte Giacomo Manzù, letter by Giacomo Manzù to Giovanni Scheiwiller, January 24, 1945.

- Joppolo, Giacomo Manzù, fig. 19.

- Ragghianti, Giacomo Manzù scultore, 69 (Sei bozzetti per il portale della cappella Motta, [Six Maquettes for the Portal of the Motta Family Chapel, 1944), figures. 42–47. Their editorial fortune began in Joppolo, Giacomo Manzù, fig. 31 (Giudizio di Salomone, The Judgment of Solomon, 1944); the same bronze was chosen as one of the two reproductions in Gruppo “L’Altana.” Mostra di Manzù, with text by L. Venturi (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1947), 6.

- Reproduced for the first time in Carrieri, Marino Marini scultore, figures 77–79.

- Reproduced for the first time in Lamberto Vitali, “Contemporary Sculptors. VII. Marino Marini,” Horizon, no. 105 (September 1948): 204.

- Carrieri, Marino Marini scultore, figures 77–79.

- Ragghianti, Giacomo Manzù scultore, 69 (Bambina sulla sedia, Young Girl on a Chair, 1947), and figures 60–61.

- Umbro Apollonio, Marino Marini scultore (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1953), 16.

- Ragghianti, Giacomo Manzù scultore, 40.