From Pomona to the Three Graces: Reshaping Female Nudity in Marino Marini’s Reliefs

Chiara Pazzaglia Chiara Pazzaglia Marino Marini, Issue 5, May 2021https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/marino-marini/

In the early-1930s Italy, monumental sculptors were commissioned to create reliefs to be situated within architecture. In the eyes of Marcello Piacentini, the leading voice of the stile littorio (“lictor style”), the constraints inherent to the relief as a sculptural form would lead to an ideal synergy between artists and architects. Already acclaimed for his free-standing sculptures, Marino Marini first presented reliefs at two major exhibitions curated by Mario Sironi: in 1932, at the Mostra della rivoluzione fascista; and in 1933, for the Milan Triennale. For an artist inclined to sculpt in the round, thinking “in relief” involved different problems. This essay aims to investigate Marini’s complex study of the fixed point of view of the relief in the works dominated by the presence of female figures. In 1939, he admitted that his main concern in the full-length figure was to analyze “the natural play of volumes” in space. Thus, transferring that figure to a surface forced him to rethink its sculptural significance. This essay specifically considers Marini’s public commissions in the 1930s, including his attempts to combine the free-standing Pomona with a fixed point of view, as well as his expressionistic turn in the 1940s, starting with his variations on the theme of the Three Graces. The traditional representation of the latter myth, at the core of the sculptor’s interests in the war years, helped Marini to investigate the relation of figures to their background. However, in his reliefs the myth was distorted in its dramatic application to modern-day content, probably looking at the contemporary work of Mario Mafai and Giacomo Manzù. In summary, this group of works helps to define the versatility with which Marini approached the sculptural theme of the female nude in relief.

In 1938, in the Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia (The illustrated Magazine of the people of Italy), Mario Sironi, one of the leading painters of the ventennio, hoped for “a return to intrinsic monumentality, a return to the meaning of architecture, a return to mural painting in its most complete signification, a return to bas-relief, that is to say, sculpture decoratively unfolded on the wall. Finally: a return to decoration.” 1 Sironi was praising the first attempts at cooperation between architects and artists in Italy. According to him, two pivotal examples were the colossal Mostra della rivoluzione fascista, held in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome in 1932, and the Fifth Milan Triennale, the following year. A third example, albeit unmentioned in the 1938 article, was the crucial competition for the Palazzo Littorio in Rome in 1934, which Sironi discussed in an article that year, before the failure of the second stage of the competition in 1937.2

It is important to note that Marino Marini took part in all three events, breathing in the atmosphere of this renewed need for monumentality.3 At the time it was common for the main architects of the Regime, such as Marcello Piacentini, to ask the artists involved in public commissions to bridle their personal creativity to benefit the larger project, subordinating themselves to the requirements of the architectural complex.4 For sculptors, this often meant producing reliefs that could be adapted to the architecture.

Up until that moment, however, Marini’s fame had been linked to the production of sculptures in the round. The effort to adapt to the language of reliefs, as required by architects, must have led him to radically revise certain themes in his production. This paper investigates Marini’s complex study of the fixed point of view of the relief. In particular, it will focus on his approach to relief-making with respect to the female nude, a genre inseparably linked, for Marini, to the third dimension. Indeed, in a well-known statement published in the journal Tempo in 1939, he confessed that his main concern in working with the full-length figure was to deepen “the natural play of volumes.”5 Therefore, the rigor of the relief must have led to a metamorphosis of the sculptural meaning of the nude.

Why choose the relief?

It is important to understand in which context the artist started to test himself with this sculptural form. Born in 1901, Marini began to work in relief around the 1920s. Unlike his colleague Arturo Martini, who since 1925 had made himself known to the general public as a sculptor of reliefs,6 for Marini the first occasion to show a relief was in 1928, at the Prima mostra provinciale d’arte in Pistoia.7 There he exhibited a tile (called Suonatore di zampogna [Bagpipe player] in the catalogue) still closely linked to the art déco style that dominated the first half of the decade. The work shows Marini’s immature maîtrise of the medium, particularly in comparison to Martini’s achievements in the same years, and it is a touchstone that must be taken into account in evaluating his full artistic career.

For a sculptor whose career was starting in the 1920s, such as Marini, the writings of the German theorist Adolf von Hildebrand were an essential point of reference for their discussion of relief. Some extracts from the critic’s most important essay, “Das Problem der Form in der bildenden Kunst” (The problem of form in painting and sculpture), appeared in an article by Antonio Maraini published in La Ronda and had significant impact on Italian culture.8 Hildebrand became the tutelary deity of the so-called “architectural” plastic style, as opposed to the “pictorial” line style that dated back to Auguste Rodin. One of the German critic’s main teachings concerned the calculation of gradation in relief plans, which was aimed at avoiding the jarring effect of a sharp contrast between planar areas and the prominent high-relief elements. Beyond these formal issues, more ideological motivations were also at stake. For the supporters of architectural style, the adoption of bas-relief imposed a healthy form of self-discipline on sculpture. This is made clear if we read the words of the conservative critic Ugo Ojetti about Maraini’s work:

The bas-relief, by forcing reality under ideal laws and within precise needs, is almost the reduction of reality to a common denominator wanted by the artist […] and excludes a priori any realistic freedom. Better: it imposes on those who look at it the point of view and the profile of those who created it. I am not saying that the bas-relief is the supreme sculpture, but it is certainly the most difficult sculpture […], nor does it allow whims and swirls of chiaroscuro, so that the modeling has to be clear and sparse and substantial, with so much that it is necessary to pass through to define the planes well and no longer.9

A series of editorial circumstances also contributed to the growing prominence of the relief. The writings on the Middle Ages by Mario Salmi, Pietro Toesca, and Emilio Lavagnino,10for instance, indirectly suggested the assimilation of that period with a neo-Romanesque era. In 1936, not by chance, Sironi admitted, again in La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia:

It is a fact that Romanesque art is close to our time. Not for a formal research that lives in itself. But the obscure and ardent force that animates the builders of cathedrals can be found in the spirit that sustains certain efforts of our time, to finally escape formal and experimental eclecticism to arrive at unitary constructions, capable of locking and enclosing every element within itself as an army frames a soldier. 11

“Unitary constructions, capable of locking and enclosing every element within itself as an army frames a soldier”: The architectural relief

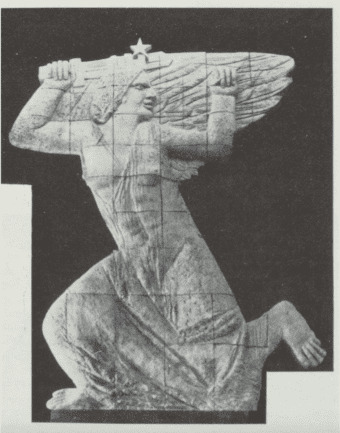

In this context, when Marino Marini was called to take part in the first important exhibitions sponsored by Mario Sironi, he was forced to make choices. During the 1932 Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, he created the since-destroyed plaster relief Italia armata (Armed Italy; figure 1), which was the visual pivot of the second room in salon C, devoted to the First World War.12 According to the exhibition’s guide, edited by Dino Alfieri and Luigi Freddi, the historical section was entrusted to Professor Antonio Monti, director of the Museo del Risorgimento and the Archivio della guerra in Milan,13 while responsibility for the purely artistic part was assigned to the painter Achille Funi, for whom “the creation of a worthy environment […] had to detach itself from pictorial assumptions to leave the field free to a solemn and severe course of architectural lines that could adequately contain the sacred and heroic relics.”14

In a context in which architecture determined the rhythm of sculpture, Marini’s work was chosen as the pendant — at the end of one room — of the static and academic Re soldato (Soldier king) made by Domenico Rambelli. Marini, in particular, was assigned the subject of Italia armata, an allegory less commonly found than the more widespread Armed Victory in official representations during the years of the regime.15 Despite the statements in the catalogue,16 the strong primitivist choices adopted for the relief largely neutralized its rhetorically charged narrative. The colossal female figure, in fact, was represented according to the iconographic scheme of Medusa in the Knielauf, or “kneeling-running” position, typical of representations of the gorgon in the archaic age (late sixth century BCE). In addition, the face’s features were markedly expressive and lacking in grace, almost like sculpture of archaic Greece (seventh to sixth centuries BCE). Thirdly, the delicate degradation of planes between the body and its almost impalpable garment set this work apart from the architectural geometry dominating the exhibition, with its clear planes and strong chiaroscuro contrasts.

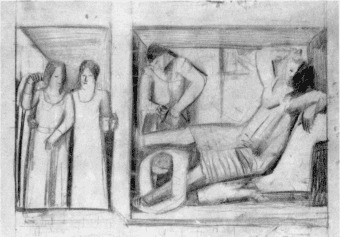

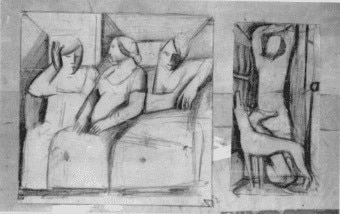

In 1933, the artist returned to tackle the sculptural theme of female figures in relief at the V Esposizione Triennale delle Arti Decorative e industriali moderne.17The exhibition was transferred for the first time from Monza to Milan, in the Palazzo dell’Arte, built for the occasion by Giovanni Muzio in Parco Sempione. Marini’s plaster relief La nuova regina (The new queen; figure 2), destroyed after the exhibition, was placed near the staircase of honor, together with Ivo Soli’s Pane (Bread) and Arturo Martini’s Mosè salvato dalle acque (Moses saved from the water). While Martini presented a provocative compendium of pictorial solutions, amidst discordances between turned reliefs in the foreground and the jagged two-dimensionality of the background, both Marini and Soli adhered to typically Novecento canons. In the preparatory drawings for the relief, Marini tuned in to Sironi’s squared and syncopated dictation, trying to emulate the clear cuts, shading, and layout of the painter’s Carta del lavoro (Charter of labor, 1931–32; figures 3–5).18 In the final rendering in bas-relief, on the other hand, he resumed the rounded and massive forms, reminiscent of Soli’s production (figure 6). The figures, defined by large compact masses, occupied the space framed by the three narrative compartments arranged vertically. The press did not fail to point the finger at these figures, defined by large, heavy, monumental blocks, as well as their cryptic subject.19 However, for Marini the event was the first opportunity to test himself with the compositional laws imposed by the unique point of view of the relief. The artist set about to study how figures rendered in high relief could be placed within a composition arranged perspectively, with architectural framing elements. In ways different than for his customary freestanding sculptures, the space of the salon required advanced consideration to prevent the perspective deformation of the relief when viewed from below. Accustomed to thinking in the round, Marino found the most natural form of expression in high relief during these two events at the beginning of the decade. A few years later, Arturo Martini gave a beautiful definition of it in his Colloqui: “All round attached. The background is but a support, not an atmosphere. It is a pedestal, instead of under the legs, on the back.”20

Yet, some examples made by Marini between 1937 and 1938 seemed to disprove this assumption. In the preparatory reliefs for the Monumento alla Vittoria in Piazza Fiume in Milan and for the Casa Littoria in Rome, he abandoned the monumental forms and Sironi’s syntax. Instead, produced a more linear type of relief, similar to the fifteenth-century stiacciato, in these years distinctive of Lucio Fontana’s plastic language.21 This change of direction was due to the need to give preeminence to the architectural structure, as was clearly required by the notices outlining the competition for the two buildings.22

In the case of the Monumento alla Vittoria, the municipality of Milan funded the erection of a modern monumental arch at the scenic point of Piazzale Fiume (now Piazza della Repubblica), to frame the avenue that led to Piazza Duca d’Aosta. Despite its ideological intention – to celebrate the victory of Fascist Italy over Ethiopia – the competition bore witness to the most creative minds of modern Italian sculpture.23 Marini won second prize together with the architects Giorgio Wenter Marini, Guido Spellanzon, and Duilio Torres. Although the project was never completed, reports published in contemporary illustrated magazines give an idea of the architectural project and the symbology that the designers sought to convey.24 Marini’s preparatory sketches for the colonialist enterprise (figure 7),25 detailing three rectangular plaster casts, shed light on an almost unknown production by the sculptor, characterized by the cancellation of volumetric values. The reliefs’ lack of finish and fast, cursive strokes do not permit full understanding of the complex figuration centered on scenes of war and triumph. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note how the African epic was told with a series of episodes developed vertically. The formal rules for managing a nondiachronic sequence of scenes as a narrative continuum were given by the Trajan’s Column, which had been the subject of an important illustrated supplement published by Edoardo Persico the year before, in Domus. 26 The resumption of the illustrious model did not only help to solve complex narrative problems, it was also part of the project, strongly advocated by Benito Mussolini, to reappropriate symbols of the Romanità.

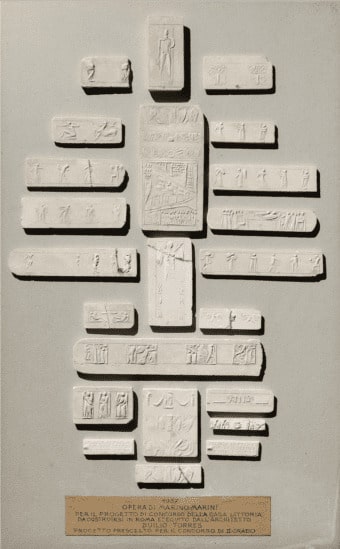

Something similar happened during the second-degree competition in 1937 for the erection of the Casa Littoria in Rome. Among the many Fascist Party headquarters built in Italy by the Regime, the building had a symbolic value of primary importance.27 Originally intended for the via dell’Impero, and then relocated to near the Mussolini Forum, the capital’s Palazzo Littorio came to define the architectural style of the Fascist era. After the failure of the competition held in 1934, the second-degree competition awarded victory to the neo-Renaissance project of the Enrico Del Debbio – Arnaldo Foschini – Vittorio Morpurgo team, with sculptural groups by Arturo Martini. However, six other projects also received recognition, and among these was a plan by the architect Duilio Torres, with reliefs by Marini.28 Torres had imagined not only reliefs on the ground floor, alternating with large windows for the central building, but also a sliding decorative layout extending over the entire surface of the tower in front.29 The preparatory sketches by Marini are devoid of the narrative trend found in his contemporaneous designs for Milan, but share with them the choice of a very low relief defined by linear strokes (figure 8).30 The small and mostly empty frames, far from the horror vacui of the reliefs for the Monumento alla Vittoria, are in fact occupied by decorative scenes interspersed with celebrative inscriptions. Being a hapax in Marini’s production, the cue for the elaboration of slender and linear figures inserted in rectangular surfaces may have come to him through his study of preclassical forms of expression, such as those ancient Mesopotamian cylinders that were illustrated in a French photographic encyclopedia published in 1936 and held in his library (figure 9).31

The two groups of reliefs from 1937 and 1938 proved to be the exceptions that confirmed the rule. A few years later, while planning sculptural works for two different architectural contexts, Marini would in fact return to more congenial forms of high relief. Most significantly, both in the relief initially intended for the Palazzo dell’INFPS in Rome (home of the Istituto Nazionale Fascista Previdenza Sociale, built in 1939–40) and in those designed for the Palazzo dell’Arengario in Milan (c. 1937–56), the choice of high relief coincided with the return to the female nude.

The sculptor worked on both projects from around 1939, but neither was completed. The Roman palace was built between those years by the young architects Mario Paniconi and Giulio Pediconi, in collaboration with Giovanni Muzio. However, Cipriano Efisio Oppo had chosen Marini among the other artists to be in charge of the decorative apparatus.32 In his preparatory relief, probably centered on the propagandistic theme of Rome versus Carthage,33 figures of Romanesque memory stand out clearly from the background, with prominence given to the female ones (figure 10).

In a similar way, in two of the five preparatory reliefs for the Palazzo dell’Arengario in Milan, the female figures, who present archaic features, are assigned a central role.34 The complex gestation of the building, created by the architects Giovanni Muzio, Piero Portaluppi, Enrico Griffini, and Pier Giulio Magistretti from 1938 onwards, is well-known.35Marini had been, together with Arturo Martini, one of the few sculptors invited by direct call. On the one hand, Martini focused on narrative panels, in which a multitude of characters interacted in frenetic scenes within complex architectural settings.36 Marini, on the other, summed up the entire meaning of the composition – almost if by synecdoche – in a few figures, representing some events of contemporary history in celebration of Fascism. Thus, in the relief kept in a private collection in Livorno (figure 11), the matronly figure in the act of domination over a man crouching at his feet symbolically alluded to the conquest of Ethiopia by Fascist Italy and the proclamation of the Empire. Similarly, in another plaster relief (figure 12; now in the Guastalla collection in Livorno), the Pomona to the left – an earthy and soft-shaped interpretation of a classical Venus – subtly refers to the mythical figure of the Virgin of the Cathedral of Milan who, according to some scholars, during the Cinque giornate di Milano in 1848, gave hope to the Italians to fight against the Austrians.37

A formal suggestion for the plastic contrast between the flat and rough background, and the turned figures emerging in high relief could have come to Marini from the reading of Auguste Rodin’s Entretiens réunis par Paul Gsell, of which Marino kept a copy in his library. In the volume he could in fact find some important teachings, especially regarding the conception of the surface as the extremity of a volume, and the vision of the shapes not in extent, but in depth.38 Already in the last years of the nineteenth century, many Italian sculptors had returned to look at the French master, taking an interest above all in the contrast, derived from Michelangelo, between the unfinished surface and the smoothness of the main figure.39 Notably even Domenico Trentacoste, who taught Marini during his student days at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, had done so.

Three figures in a space

The relationship between the highly finished state of the nude and the indefinite background continued to interest Marino Marini in a series of three reliefs from 1943.40 Although no architectural destination was envisaged for them, during his years spent in Tenero (Locarno), Marini still considered the relief to be the best form to strengthen the relationship between figure and contour. By choosing malleable materials such as plaster and bronze, he subjected both the figures and the background to intense superficial work, making the material magmatic and vibrant; yet, he did not push the hiatus between the two planes to the extreme, as Rodin had done. In general, what attracted him most was the challenge of harmonizing different female figures within the given space of a tile. In these years, indeed, he was intensely rethinking the traditional theme of the Three Graces, as testified by Raffaele Carrieri’s gift to him, in 1942, of Pericle Ducati’s volume Pittura etrusca-italo-greca e romana (Etruscan, Italian-Greek and Roman painting, 1941), with a reproduction of the famous fresco at Pompeii of this subject.41

Many sculptors of Marini’s time were testing themselves against this theme from ancient myth, and with varying attitudes. There were those who, like Arturo Martini, had completely distorted the compositional order of the theme, reducing the Graces to a mere pretext for arranging three bodies in space.42 By contrast, others, like Marcello Mascherini, interpreted the subject with a joyful and vital spirit, à la Pierre-Auguste Renoir, after the Second World War.43

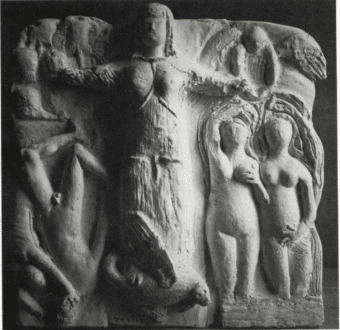

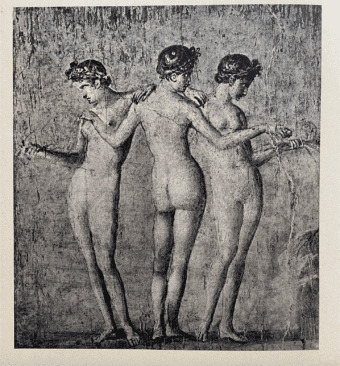

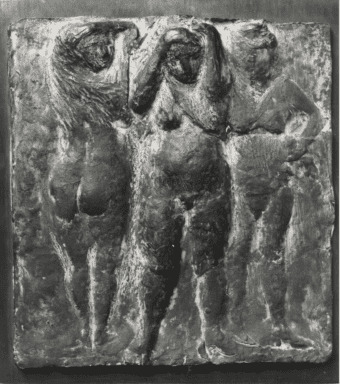

Marini, in the 1943 relief known as Le tre Grazie (figure 13), introduced variations to the conventional iconography, inverting the poses of the nudes and creating a dense central composition. Some compositional ideas could perhaps derive from photographic reproductions of the fresco from Pompeii, now at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. The enlargement reproduced in Ducati’s volume (figure 14), with its low horizon and close-up on the three figures, allowed for the reinterpretation of the group in a monumental sense, regardless of the airy and spacious composition of the ancient painting.

Two other pieces made by Marini in 1943, given the generic title of Composizione (Composition), seem to be variations of the same theme, but with significant differences. While maintaining a composition based on three figures in one tile, they reinvent the characters’ poses to such an extent that they almost no longer resemble the original, ancient model. The contours between the figures and the background are also hollowed out and ragged, so that the boundary between them is impalpable. Finally, in the relief also known as Le tre signore a passeggio (The ladies on a walk; figure 15),44 built with broken shapes reminiscent of Cubist grammar, some details of contemporary life (such as the high heels of the two women at the center and to the right) remove the figures from the timeless universe of ancient myth.

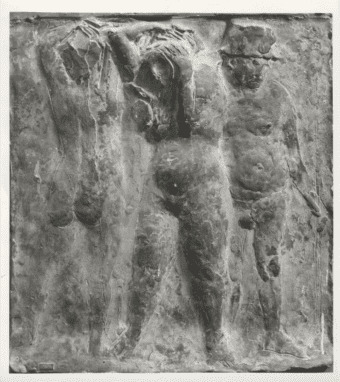

The other Composizione made in 1943 (figure 16) partly replicates the formal structure already described. The relief is occupied by three figures: the first two female, the third male. The two women, in particular, are depicted bringing their hands to their heads, in a gesture of despair. The one on the left is seen from behind, her body in torsion; the central one, in a frontal view. The main change in relation to Le tre signore a passeggio concerns the third character on the right, as the female figure wearing heeled shoes is here replaced by a corpulent male figure wearing a hat.

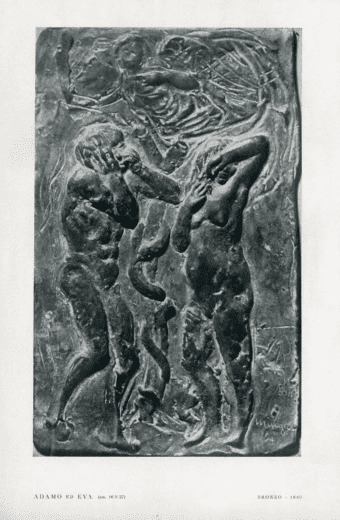

Both the tragic pose of the figures on the left and at the center and the mysterious male nude on the right seem to take into account the art scene of their time. In the early 1940s, several Italian artists had portrayed the disasters of the Second World War by turning to the Christian iconographic tradition. For instance, the bas-relief Adamo ed Eva (Adam and Eve, 1940, from the Capricci series; figure 17) by the Bolognese sculptor Luciano Minguzzi modernized the fifteenth-century Progenitori painted by Masaccio for the Brancacci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, reworking the pair’s poses. In fact, as one of his drawings published in the magazine Architrave in 1940 shows,45 Minguzzi must have found a model of expressive gestures in the Renaissance painter, who was, in those years, the object of widespread study.46 Although it is difficult to imagine that Marini would have seen this panel, which was exhibited and reproduced in a volume for the first time in 1946,47 the formal closeness between the two reliefs prompts the supposition that, independently from Minguzzi, Marini had found an interesting visual source of eloquent gestures in Masaccio’s depiction of the expulsion of Adam and Eve.

The case is different for the male nude on the right of Marini’s Composizione. Represented in an almost humiliating nudity – with protruding belly, headgear, and lance in his hand – this figure provides a good illustration of Marini’s ongoing dialogue with one of Mario Mafai’s Fantasies. Now in the collection of the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Mafai’s Fantasia (Processione) (Fantasy, [Procession], 1939–43; figure 18) depicts scenes of violence and atrocities perpetrated by the Nazi and Fascist regimes. With dense and expressionistic brushstrokes, it concentrates mercilessly on the massacring perpetrators, who, with tragic irony, are represented naked and fat, equipped only with hats, boots, weapons, and flags.48 Marini had certainly been able to see some of Mafai’s paintings in person, for he shared an exhibition with Mafai from March 14–29, 1941, at the Galleria Genova.49 On that occasion, two of Mafai’s Fantasies were exhibited (Fantasia n. 7, 1939-41, and Fantasia n. 8, 1939-41).

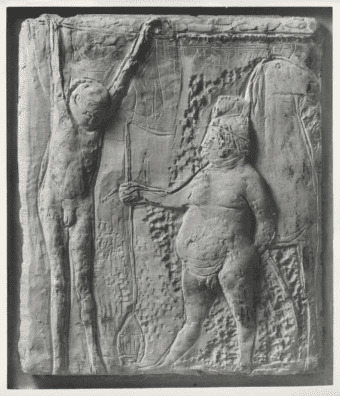

If the work of Mafai, who had recently won the Bergamo Prize, suggested to Marini a nonliteral way of alluding to contemporary history, other artist’s production did so as well. Indeed, also in 1941, an exhibition in Milan caused such a scandal in the ecclesiastical and political world that neither Marini nor Mafai could have been unaware of it. At the end of January 1941, the Barbaroux Gallery there hosted a solo exhibition of Giacomo Manzù’s heterogeneous works made between 1931 and 1940, including four bronze panels made at the beginning of 1940, which belonged to the famous cycle of Cristo nella nostra umanità (Christ in Our Humanity).50 If the reliefs were praised by the critic Cesare Brandi in Le Arti, the institutional magazine of the Ministero dell’Educazione Nazionale, they were not immune from criticism either – a violent campaign was being carried out by the Regime and the Catholic press.51 What caused the stir was not only the representation of Christ as a naked man, helpless in his fragility, but also the nearby presence of an obese prostitute with deformed limbs. Moreover, the representation of Longinus, a Roman soldier typically included in depictions of Christ’s Crucifixion, as a naked man equipped only with a nailed helmet, brought the scene back to the contemporary tragedies of the Second World War.

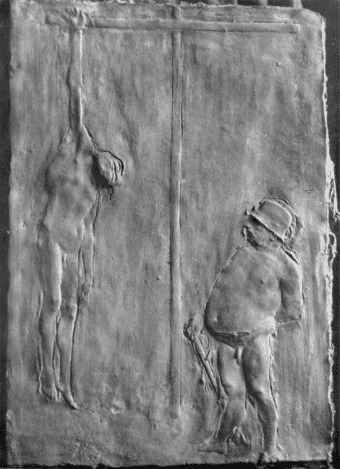

Manzù may have given Marini, above all, two lessons. First, he could have indicated a more subtle way to allude to the present through the figure of the soldier deprived of everything but weapons of destruction. Second, he may also have helped him understand more deeply the communicative power of the female nude. A relief by Marini (figure 19; a variant of which exists in the Fototeca of the Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia) seems to document his attention to the Manzù series. The work is traditionally dated to 1939, but it seems necessary to postpone its chronology to at least the 1940s.52 Although doubts remain as to the exact chronology of the piece, its compositional revival of Manzù’s bas-relief Crocifissione con soldato (Crucifixion with Soldier, 1942; figure 20) is undeniable.

Conclusion

This essay has highlighted the versatility with which Marino Marini approached the sculptural theme of the nude in relief. At the beginning of the 1940s, the female figure, in some cases coinciding with the Pomona, lent itself to taking on various meanings in line with the rhetorical content required of an architectural destination. Most importantly, however, the nude served to test the insertion of a three-dimensional sculptural theme within an architectural structure, with a unique point of view. Similarly, the theme of the Three Graces, as of 1943, helped Marini study the problem of the relationship between figure and ground. The Arcadian myth was distorted to lend itself to conveying, more dramatically, modern-day content, in dialogue with the contemporary works of Mario Mafai and Giacomo Manzù. In sum, for a sculptor accustomed to working on sculptures in the round, the relief was a formal pretext to study the theme of the nude, regardless of any reference to content.

Bibliography

Alfieri, Dino and Luigi Freddi, eds. Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista: 1 decennale della Marcia su Roma. Rome: Partito nazionale fascista, 1933.

Appella, Giuseppe, ed. Mario Mafai. “Le Fantasie.” Rome: Edizioni della Cometa, 1989.

Bazzano, Nicoletta. Donna Italia. L’allegoria della Penisola dall’antichità ai giorni nostri. Costabissara: Angelo Colla editore, 2011.

Bignami, Silvia. “‘Lavoro che mi sta a cuore, perché va in piazza.’ Arte pubblica e concorsi a Milano negli anni Trenta del Novecento.” In L’arte pubblica nello spazio urbano. Committenti, artisti, fruitori, edited by Carlo Birrozzi and Marina Pugliese, 4–19. Milan: Bruno Mondadori, 2007.

Bignami, Silvia. “Arturo Martini e la storia eroica del fascismo. Alcune novità degli Atti del Comune di Milano.” In Per Ofelia. Studi su Arturo Martini, edited by Claudia Gian Ferrari and Matteo Ceriana, 79–94. Milan: Charta, 2009.

Bossaglia, Rossana, and Alberto Crespi, eds. L’ISIA di Monza. Una scuola d’arte europea. Milan: Amilcare Pizzi editore, 1985.

Brandi, Cesare. “Una mostra di Manzù.” Le Arti 3 (February–March 1941): 202–04.

Coen, Ester, and Simonetta Lux, eds. 1935: gli artisti nell’università e la questione della pittura murale. Rome: Bonsignori Editore, 1985.

Calvesi, Maurizio, Enrico Guidoni, and Simonetta Lux, eds. E42: Utopia e scenario del regime. Venice: Marsilio, 1987: 477–80.

Campiglio, Paolo ed. Lucio Fontana. La scultura architettonica in Italia. Nuoro: Ilisso, 1995.

Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura. Edited by Giovanni Carandente. Milan: Skira, 1998.

Cinelli, Barbara. “Manzù e l’arte sacra: un itinerario complesso.” In Manzù. Dialoghi sulla spiritualità, con Lucio Fontana, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Davide Colombo, 34–39. Milan: Electa, 2016.

Cinelli, Barbara and Fernando Mazzocca, eds. Fortuna visiva di Masaccio nella grafica e nella fotografia. Florence: S.P.E.S. Editrice, 1979.

“Corriere architettonico della rassegna: concorso per il monumento alla vittoria in Milano.” Rassegna di architettura, nos. 7–8 (July–August 1937): 305–11.

Crespi, Alberto. “1931–1941: Marino Marini all’ISIA di Monza. Un decennio d’esperienza didattica e di crescita artistica.” In Marino Marini. Gli archetipi, edited by Daniele Astrologo Abadal and Alberto Montrasio, 31–41. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2008.

D’Amico, Fabrizio and Flaminio Gualdon, eds. Mario Mafai. Le fantasie. Bologna: Nuova Alfa, 1990.

Ducati, Pericle, ed. Pittura etrusca-italo-greca e romana. Novara: Istituto geografico De Agostini, 1941.

Fabi, Chiara, ed. Marino Marini. La collezione del museo del Novecento. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2016.

Fabi, Chiara. “La via del realismo.” In Manzù. Dialoghi sulla spiritualità, con Lucio Fontana, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Davide Colombo, 56–58. Milan: Electa, 2016.

Fagone, Vittorio, Giovanni Ginex, and Tullia Sparagni, eds. Muri ai pittori. Pittura murale e decorazione in Italia 1930–1950. Milan: Mazzotta, 1999.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Auguste Rodin e gli scultori italiani (1889–1915). 1.” Prospettiva. Rivista di storia dell’arte antica e moderna, no. 89–90 (January–April 1998).

Fergonzi, Flavio. “‘Una storia d’amore’: un ciclo perduto di Arturo Martini alla Terza Biennale Romana.” Ricerche di Storia dell’arte, no. 30 (1986).

Fontana, Sara. “‘Io resto nel mio studio a scolpire quel che ho in mente.’ Alcune tracce di Marino ‘pubblico’ e ‘monumentale.’” In Marino Marini. Gli archetipi, edited by Daniele Astrologo Abadal and Alberto Montrasio, 13–27. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2008.

“Il concorso di secondo grado per la Casa Littoria in Roma.” Architettura 16, no. 12 (December 1937): 733-735.

Irace, Fulvio. Giovanni Muzio, 1893-1982: opere. Milan: Electa, 1994: 124-135.

Jahier, Piero, ed. Luciano Minguzzi. Scultore. Bologna: Casa Editrice dell’Orsa, 1946.

Lavagnino, Emilio. Il medioevo. L’età paleocristiana e l’alto medioevo – L’arte romanica. Il gotico e il Trecento. Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 1936.

Mario Mafai, Marino Marini in una mostra nelle nostre sale. Genoa: Galleria Genova, 1941. Exhibition catalogue.

Mangione, Flavio, ed. Le case del Fascio in Italia e nelle terre d’oltremare. Rome: Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali, Direzione generale per gli archivi [Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. General direction of Archives], 2003.

Maraini, Antonio. “‘Il problema della forma’ di Adolf Hildebrand.” La Ronda 4, no. 11 (November 1922): 739–48.

Maraini, Antonio. “‘Il problema della forma’ di Adolf Hildebrand.” La Ronda 5, no. 12 (December 1923): 831–38.

Marini, Marino. “Le mie sculture,” Tempo 4, no. 29 (December 14, 1939).

Martini, Arturo. In Colloqui sulla scultura 1944–1945 raccolti da Gino Scarpa, edited by Nico Stringa. Treviso: Edizioni Canova, 1997.

Maugeri, Giacomo. “Non più spine nel cuore di Manzù.” Omnibus (June 9, 1947).

Monti, Antonio. Le cinque giornate di Milano. Milan: Apollon, 1944.

Ojetti, Ugo. “Lo scultore Antonio Maraini.” Dedalo 3 (1921): 743–58.

Ojetti, Ugo. “La quinta Triennale milanese.” Il Corriere della Sera (May 10, 1933).

Panzetta, Alfonso, ed. Marcello Mascherini scultore (1906–1983). Catalogo generale dell’opera plastica. Turin: Allemandi, 1998.

Papini, Roberto. “La Triennale milanese delle arti.” L’Illustrazione italiana 60, no. 23 (June 4, 1933): 850–76.

Pazzaglia, Chiara. “Marino monumentale: i cinque rilievi per l’Arengario di Milano”, Studi di scultura 1, no. 1 (2019): 138–57.

Persico, Edoardo. Arte romana. La scultura romana e quattro affreschi della villa dei misteri. Milan: Domus 1935.

Piacentini, Marcello. “Il progetto definitivo della casa Littoria a Roma.” Architettura 16, no. 12 (December 1937): 702–04.

Piacentini, Marcello. “La legge per gli artisti.” Primato 3, no. 11 (November 1942): 209–10.

Purini, Franco, Simonetta Lux, and Giorgio Ciucci, eds. Marcello Piacentini architetto 1881–1960, December 16-17, 2013. Rome: Gangemi, 2013. Exhibition catalogue.

Pontiggia, Elena. “Opere distrutte o non realizzate. Monumento alla Vittoria d’Etiopia in piazza Fiume.” In Arturo Martini, edited by Claudia Gian Ferrari, Elena Pontiggia, and Livia Velani, 253. Milan: Skira, 2006.

Portoghesi, Paolo, Soffitta Andrea, and Mangione, Flavio eds. L’architettura delle Case del Fascio. Florence: Alinea, 2006.

Prima mostra provinciale d’arte. Pistoia: Arte della stampa, 1928.

Rodin, Auguste. L’art. Entretiens réunis par Paul Gsell. Lausanne: Mermod, 1946.

Salmi, Mario. La scultura romanica in Toscana. Florence: Rinascimento del Libro, 1928.

Savorra, Massimiliano. Enrico Agostino Griffini. La casa, il monumento, la città. Napoli: Electa, 2000.

Schnapp, Jeffrey T., ed. Anno X: la Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista del 1932. Pisa: Istituti editoriali e poligrafici internazionali, 2003.

Sironi, Mario. “Monumentalità fascista.” La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia 13, no. 11 (November 1934): 84–93.

Sironi, Mario. “Secolo undecimo.” La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia 14, no. 9 (September 1936): 31-39.

Sironi, Mario. “Il Volto.” La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia 16, no. 4 (April 1938): 36–38.

Tedeschi, Enrico. “Concorso per il monumento alla Vittoria di Milano.” Architettura 16, no. 11 (November 1937): 646–50.

Terenzi, Claudia. “Gli anni difficili.” In Mario Mafai. 1902–1965, Una calma febbre di colori, edited by Claudio Strinati, Netta Vespignani, Giuseppe Appella, et al., 27–29. Milan: Skira, 2004.

Toesca, Pietro. Storia dell’arte italiana. I Il Medioevo. Turin: Utet, 1927.

Vianello, Gianni, Nico Stringa, and Claudia Gian Ferrari, eds. Arturo Martini. Catalogo ragionato delle sculture. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 1998.

Villani, Marcello. I Palazzi delle Esedre. Rome: Gangemi, 2012.

Vitali, Lamberto. “Pittura murale alla Triennale.” Domus, no. 66 (June 1933): 286–91.

Vitali, Lamberto, ed., Marino Marini. Florence: Edizioni U, 1946.

Vigneau, André, ed. Le Musée du Louvre. Mésopotamie, Canaan, Chypre, Grèce. Photographies inédites par Andre Vigneau. Paris: Édtitions Tel, 1936: 77-78.

- “Il ritorno alla monumentalità intrinseca, il ritorno al significato dell’architettura, il ritorno alla pittura murale nella sua più completa significazione, il ritorno al bassorilievo cioè scultura dispiegata decorativamente sulla parete. Infine: il ritorno alla decorazione.” See Mario Sironi, “Il Volto,” La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia 16, no. 4 (April 1938): 36–38. All translations, unless otherwise stated, are the author’s.

- See Mario Sironi, “Monumentalità fascista,” La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia 13, no. 11 (November 1934): 84–93.

- The main publications that have dealt with the sculptor’s monumental production are Sara Fontana, “‘Io resto nel mio studio a scolpire quel che ho in mente.’ Alcune tracce di Marino ‘pubblico’ e ‘monumentale,’” in Marino Marini. Gli archetipi, ed. Daniele Astrologo Abadal and Alberto Montrasio (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2008), 47–53; and Marino Marini. La collezione del museo del Novecento, ed. Chiara Fabi (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2016), 13-27.

- See, for example, Piacentini’s statement in the referendum promoted by “Primato” in 1942: Marcello Piacentini, “La legge per gli artisti,” Primato 3, no. 11 (November 1942): 209–10. On the architect in general, see Marcello Piacentini architetto 1881–1960, December 16–17, 2013, ed. Franco Purini, Simonetta Lux and Giorgio Ciucci (Rome: Gangemi, 2013).

- “La figura, la statua impone, invece, una più vasta ricerca di forme, di linee, di masse. Le mie donne, che alcuni trovano goffe, rispondono a questa preoccupazione. Nella figura, io mi propongo di approfondire, nell’insieme sempre più unito, più fermo, e pure libero e sciolto, il giuoco naturale dei volumi.” Marino Marini, “Le mie sculture,” Tempo 4, no. 29 (December 14, 1939).

- See Flavio Fergonzi, “‘Una storia d’amore’: un ciclo perduto di Arturo Martini alla Terza Biennale Romana,” Ricerche di Storia dell’arte, no. 30 (1986): 88–98.

- See Prima mostra provinciale d’arte (Pistoia: Arte della stampa, 1928), 29.

- See Antonio Maraini, “‘Il problema della forma’ di Adolf Hildebrand,” La Ronda 4, no. 11 (November 1922): 739–48, and “‘Il problema della forma’ di Adolf Hildebrand,” La Ronda 5, no. 12 (December 1923): 831–38.

- “Il bassorilievo, costringendo la realtà sotto leggi ideali e dentro necessità precise, è quasi la riduzione della realtà a un comune denominatore voluto dall’artista […] ed esclude a priori qualunque libertà realistica. Meglio: impone a chi lo guarda il punto di vista e il profilo di chi lo ha creato. Non dico che il bassorilievo sia il sommo della scultura, ma certo è la scultura più difficile […], né permette capricci e svolazzi di chiaroscuro, così che la modellatura v’ha da essere netta e parca e sostanziale, con quel tanto che occorre di trapassi per definire bene i piani e non più.” Ugo Ojetti, “Lo scultore Antonio Maraini,” Dedalo 3 (1921): 744–45:

- See, for example, Mario Salmi, La scultura romanica in Toscana (Florence: Rinascimento del Libro, 1928); Pietro Toesca, Storia dell’arte italiana. I Il Medioevo (Turin: Utet, 1927); and Emilio Lavagnino, Il medioevo: L’età paleocristiana e l’alto medioevo – L’arte romanica. Il gotico e il Trecento (Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 1936).

- “È un fatto che l’arte romanica è vicina al nostro tempo. Non per una ricerca formale che viva a sé. Ma la forza oscura e ardente che anima i costruttori delle cattedrali può trovare riscontro nello spirito che sorregge certi sforzi del tempo nostro, di sfuggire finalmente all’eclettismo formale e sperimentale per giungere alle costruzioni unitarie, capaci di serrare e racchiudere in sé ogni elemento come un esercito inquadra un soldato.” Mario Sironi, “Secolo undecimo,” La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia 14, no. 9 (September 1936): 31–39.

- On the exhibition, see Jeffrey T. Schnapp, ed., Anno X: la Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista del 1932 (Pisa: Istituti editoriali e poligrafici internazionali, 2003).

- See Dino Alfieri and Luigi Freddi, ed., Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista: 1 decennale della Marcia su Roma (Rome: Partito nazionale fascista, 1933).

- “La parte artistica è stata ideata e realizzata dal pittore Achille Funi […]. L’artista ha subito pensato che […] il modo migliore di realizzare degnamente l’ambiente destinato ad ospitare il periodo glorioso della guerra italiana dovesse staccarsi da presupposti pittorici per lasciare libero il campo ad un solenne e severo andamento di linee architettoniche che potesse adeguatamente contenere i cimeli sacri ed eroici.” Freddi Alfieri, Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista (1933), 94.

- See Nicoletta Bazzano, Donna Italia. L’allegoria della Penisola dall’antichità ai giorni nostri (Costabissara: Angelo Colla editore, 2011).

- The text in the catalogue stresses the rhetorical values of the work: “La statua dell’Italia armata, suggerita dal pittore Funi, è opera dello scultore Marino Marini. Rude e vigorosa, protesa come nell’impeto d’un volo, sta a significare la purezza semplice ed eroica della nostra stirpe eternamente giovane contro certi cerebralismi malati e artificiosi delle razze decadenti. Il grande bassorilievo esprime vigore, volontà quadrata, romana, uno slancio rattratto, un’energia contenuta, ieratica, un impeto che già comprende le conquiste della meta. Contrasti rudi, forme irrigidite nello sforzo ma ingentilite da un ermetico sorriso di grazia e di certezza.” (“The statue of Armed Italy, suggested by the painter Funi, is the work of the sculptor Marino Marini. Rude and vigorous, protruding as if in the rush of a flight, it signifies the simple and heroic purity of our eternally young lineage against certain sick and artificial cerebralisms of decadent races. The great bas-relief expresses vigor, a square, Roman will, a saddened impulse, a contained, hieratic energy, an impetus that already understands the conquests of the goal. Rough contrasts, forms stiffened in effort but softened by a hermetic smile of grace and certainty. Integral nobility of all the layers of a race that yearns for the future without betraying its origins, and civilization of a people that has reached all the peaks and seeks others, a millenary civilization that reunites the ancient with the present and tends to perpetuate itself with the will of power and freedom of harmony”). Freddi, Alfieri, Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista (1933), 93.

- The exhibition was the first one organized in the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan. It took place from May to September 1933 and featured numerous wall paintings, mosaics, and plastic works by the most notable Italian artists of the time. Martini’s relief is reproduced in Arturo Martini: catalogo ragionato delle sculture, ed. Gianni Vianello, Nico Stringa, and Claudia Gian Ferrari (Vicenza: Neri Pozza Editore, 1998), 239, no. 356. For Soli’s work, see instead http://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/fotografie/schede/IMM-3u010-0000027/ (accessed March 25, 2021). On the general issue of wall decoration in the 1930s, see 1935: gli artisti nell’università e la questione della pittura murale, ed. Ester Coen and Simonetta Lux (Rome: Bonsignori Editore, 1985); and Muri ai pittori. Pittura murale e decorazione in Italia 1930–1950, ed. Vittorio Fagone, Giovanni Ginex, and Tullia Sparagni (Milan: Mazzotta, 1999).

- The three drawings refer to the two bottom panels of Marini’s relief La nuova regina, while no preparatory drawing of the top panel has been preserved. One of the drawings, moreover, is related to a preliminary stage of the composition, when Marini had thought of two rather than three female figures. At an unknown date, the three works became part of the collection in Lissone of the heirs of Angelo Arosio, a pupil of the sculptor at the Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche di Monza (ISIA). They were exhibited for the first time in 2008, during a show held at the Bodini Museum in Gemonio (Varese). I would like to thank Alberto Crespi for this information. See Alberto Crespi, “1931–1941: Marino Marini all’ISIA di Monza. Un decennio d’esperienza didattica e di crescita artistica,” in Marino Marini. Gli archetipi, ed. Daniele Astrologo Abadal and Alberto Montrasio (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2008), 31–41 and L’ISIA di Monza. Una scuola d’arte europea, ed. Rossana Bossaglia and Alberto Crespi (Milan: Amilcare Pizzi editore, 1985), 118–120.

- Lamberto Vitali, in the magazine Domus, condemned the monotony of the relief, which was worsened by the presence of “heavy figures” (“figure pesanti”) around the queen. Roberto Papini agreed on this aspect, labeling Marini’s characters as “swollen figures, draggy, with madhouse faces” (“figure gonfie, sciancate, con facce ebeti da frenocomio”) on the pages of L’Illustrazione italiana. In Il Corriere della Sera, Ugo Ojetti highlighted a point neglected by other reviewers, the “incomprehensible fairy tale with three squares, populated by stocky and apoplectic giants” (“incomprensibile favola a tre riquadri, popolati di colossi tozzi e apoplettici”). See Lamberto Vitali, “Pittura murale alla Triennale,” Domus, no. 66 (June 1933): 286–91; Roberto Papini, “La Triennale milanese delle arti,” L’Illustrazione italiana 60, no. 23 (June 4, 1933): 850–76; and Ugo Ojetti, “La quinta Triennale milanese,” Il Corriere della Sera, May 10, 1933.

- “Tutto tondo attaccato. Il fondo non è che un appoggio, non un’atmosfera. È un piedistallo, invece che sotto le gambe, sulla schiena.” Colloqui sulla scultura 1944–1945 raccolti da Gino Scarpa, ed. Arturo Martini and Nico Stringa (Treviso: Edizioni Canova, 1997), 299.

- To learn more about Lucio Fontana’s production of reliefs in the 1930s, see Lucio Fontana. La scultura architettonica in Italia, ed. Paolo Campiglio (Nuoro: Ilisso, 1995).

- With regard to the announcement of the competition for the Casa Littoria in Rome, see the extract published in Marcello Piacentini, “Il progetto definitivo della casa Littoria a Roma,” Architettura 16, no. 12 (December 1937): 702–04. The history of the Monumento alla Vittoria of Milan is detailed in Silvia Bignami, “‘Lavoro che mi sta a cuore, perché va in piazza.’ Arte pubblica e concorsi a Milano negli anni trenta del Novecento,” in L’arte pubblica nello spazio urbano. Committenti, artisti, fruitori, ed. Carlo Birrozzi and Marina Pugliese (Milan: Bruno Mondadori, 2007): 4–19.

- The first prize went to the project by architects Antonio Carminati and Giuseppe Mazzoleni, with plastic interventions by Martini; the second prize went to Giorgio Wenter Marini, Guido Spellanzon, and Duilio Torres, with sculptures by Marini; the third prize went to the project by architects Renzo Zavanella and Enrico Ciuti, who invited Lucio Fontana for the sculptural part. On the winning project by Antonio Carminati and Giuseppe Mazzoleni, with sculptures by Martini, see Silvia Bignami, “Arturo Martini e la storia eroica del fascismo. Alcune novità degli Atti del Comune di Milano,” in Per Ofelia. Studi su Arturo Martini, ed. Claudia Gian Ferrari and Matteo Ceriana (Milan: Charta, 2009), 83; and Elena Pontiggia, “Opere distrutte o non realizzate. Monumento alla Vittoria d’Etiopia in piazza Fiume,” in Arturo Martini, ed. Claudia Gian Ferrari, Elena Pontiggia and Livia Velani (Milan: Skira, 2006): 253. On the other hand, for the third award-winning project by Renzo Zavanella and Enrico Ciuti, with Lucio Fontana, see Lucio Fontana, ed. Paolo Campiglio, 105–08.

- The winning projects are illustrated in Enrico Tedeschi, “Concorso per il monumento alla Vittoria di Milano,” Architettura 16, no. 11 (November 1937): 646–50. From the reportage that the magazine Rassegna di architettura devoted to the competition, it is possible to learn more about the symbolism sought by Torres for the project: the three elements of the arch were to represent the “three great phases through which Fascism passed, in order to achieve the completeness of its manifestations that generated the creation of the empire (that is: the preparation of the people, the development of the order and the total introduction of the people into the state)” (“le tre grandi fasi attraverso le quali il fascismo è passato, per raggiungere la completezza delle sue manifestazioni che ha generato la creazione dell’impero (ossia: La preparazione del popolo, lo sviluppo degli ordinamenti e la immissione totale del popolo nello stato)”); the two allegorical groups were to symbolise “Faith and Strength” (“la Fede e la Forza”); the six large narrative bas-reliefs inside the arch were to represent both “the victories that the monument glorifies” (“le vittorie che il monumento glorifica”) and “the first creators of the same victories” (“i creatori primi delle stesse vittorie”). “Corriere architettonico della rassegna. Concorso per il monumento alla vittoria in Milano,” Rassegna di architettura, nos. 7–8 (July–August 1937): 305–11.

- See Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia, Fondo Giuseppe Torres, sub-fondo Duillio Torres (1914–1953), Armadio 1-A/6. “Opera di Marino Marini per il progetto del monumento alla Vittoria in Milano eseguito dall’architetto Duilio Torres, 1938.”

- See Edoardo Persico, Arte romana: la scultura romana e quattro affreschi della villa dei misteri (Milan: Domus 1935).

- For an overview of the Fascist headquarters built in Italy and the colonial possessions during the years of the Regime, see Flavio Mangione, ed., Le case del Fascio in Italia e nelle terre d’oltremare (Rome: Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali. Direzione generale per gli archivi, 2003); and Paolo Portoghesi, Andrea Soffitta, and Flavio Mangione, L’architettura delle Case del Fascio (Florence: Alinea, 2006).

- See Marcello Piacentini, “Il progetto definitivo della Casa Littoria in Roma,” 699–705. Other competitors who stood out were, in alphabetical order: the group B. Del Giudice – G. Errera – A. Folin; O Frezzotti; L. Moretti; G. Rapisardi; and the group M. Ridolfi – V. Cafiero – E. La Padula – E. Rossi.

- The image of the project is reproduced in “Il concorso di secondo grado per la Casa Littoria in Roma,” Architettura 16, no. 12 (December 1937): 733–35.

- Archivio Progetti, Fondo Giuseppe Torres, Università Iuav di Venzia, sub-fondo Duillio Torres (1914–1953), Armadio 1-A/6. “Opera di Marino Marini per il progetto di concorso della casa Littoria da costruirsi in Roma eseguito dall’architetto Duilio Torres, 1937.”

- See Le Musée du Louvre. Mésopotamie, Canaan, Chypre, Grèce. Photographies inédites par Andre Vigneau, ed. André Vigneau (Paris: Édtitions Tel, 1936): 77–78.

- Along with Marini, the artists Quirino Ruggeri, Mirko Basaldella, and Oddo Aliventi were chosen for the decoration. Marini later resigned for “health reasons” and was replaced by Giuseppe Mazzullo. To learn more about the history of the I.N.F.P.S. Building, one of the two “Palazzi delle Esedre” built in view of the E42 (Universal Exposition in 1942) by Mario Paniconi, Giulio Pediconi, and Giovanni Muzio, see Marcello Villani, I Palazzi delle Esedre (Rome: Gangemi, 2012). On its decoration, with photographic documentation of the preparatory relief made by Marini, see E42: Utopia e scenario del regime, ed. Maurizio Calvesi, Enrico Guidoni, and Simonetta Lux (Venice: Marsilio, 1987), 477–80.

- This was in fact the theme of the relief of the sculptor called in Marini’s place, Giuseppe Mazzullo.

- For the history of the reliefs, see Chiara Pazzaglia, “Marino monumentale. I cinque rilievi per l’Arengario di Milano,” Studi di scultura 1, no. 1 (2019): 138–57.

- For the history of the building, see Fulvio Irace, Giovanni Muzio, 1893–1982. Opere (Milan: Electa, 1994), 124–35; and Massimiliano Savorra, Enrico Agostino Griffini: la casa, il monumento, la città (Napoli: Electa, 2000), 115–99.

- See Arturo Martini. Catalogo ragionato delle sculture, ed. Gianni Vianello, Nico Stringa, and Claudia Gian Ferrari (Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 1998): 352–53.

- According to a few historians such as Antonio Monti, during the Austrian occupation of Milan, Luigi Torelli and Scipione Bagaggi climbed the highest spire of the Duomo to hoist the tricolour on the Madonnina and spur their compatriots to resistance. See Antonio Monti, Le cinque giornate di Milano (Milan: Apollon, 1944); and Chiara Pazzaglia, “Marino monumentale, I cinque rilievi per l’Arengario di Milano”: 153.

- “Quand tu sculpteras désormais, ne vois jamais les formes en étendue, mais toujours en profondeur…Ne considère jamais une surface que comme l’extrémité d’un volume, comme la pointe plus ou moins large qu’il dirige vers toi. […] Ce principe fut pour moi d’une étonnante fécondité. Je l’appliquai à l’exécution des figures. Au lieu d’imaginer les différentes parties du corps comme des surfaces plus ou moins planes, je me les représentai comme les sailles des volumes intérieurs.” See Auguste Rodin, L’art. Entretiens réunis par Paul Gsell (Lausanne: Mermod, 1946).

- See Flavio Fergonzi, “Auguste Rodin e gli scultori italiani (1889–1915).1,” Prospettiva. Rivista di storia dell’arte antica e moderna, nos. 89–90 (January–April 1998): 40–73.

- See Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, ed. Giovanni Carandente (Milan: Skira, 1998): 154–55, nos. 213–15.

- See Pericle Ducati, ed., Pittura etrusca-italo-greca e romana (Novara: Istituto geografico De Agostini, 1941). The copy of the volume in Marini’s library contains Raffaele Carrieri’ inscription: “Ricordati del tuo Raffaele Carrieri. Milano 1942.”

- See Arturo Martini’s maiolica tile Three Graces (1928), in Arturo Martini. Catalogo ragionato delle sculture, no. 216.

- See Marcello Mascherini’s bronze bas-relief Three Graces (1948) in Marcello Mascherini scultore (1906–1983). Catalogo generale dell’opera plastica, ed. Alfonso Panzetta (Turin: Allemandi, 1998), no. 273.

- This is the title given to the relief in Lamberto Vitali, ed., Marino Marini (Florence: Edizioni U, 1946), no. 26.

- See Luciano Minguzzi’s drawing inspired by Masaccio, published in Architrave I, no. 4 (March 1, 1941): 4.

- See Fortuna visiva di Masaccio nella grafica e nella fotografia, ed. Barbara Cinelli and Fernando Mazzocca (Florence: S.P.E.S. Editrice, 1979).

- See Luciano Minguzzi. Scultore, ed. Piero Jahier (Bologna: Casa Editrice dell’Orsa, 1946).

- On Mafai’s cycle of twenty-three small and medium-sized paintings, see Claudia Terenzi, “Gli anni difficili,” in Mario Mafai. 1902–1965, Una calma febbre di colori, ed. Claudio Strinati, Netta Vespignani, Giuseppe Appella, et al. (Milan: Skira, 2004), 27–29; Mario Mafai. “Le Fantasie,” ed. Giuseppe Appella (Rome: Edizioni della Cometa, 1989); and Mario Mafai. Le fantasie, ed. Fabrizio D’Amico and Flaminio Gualdoni (Bologna: Nuova Alfa, 1990).

- See Mario Mafai, Marino Marini in una mostra nelle nostre sale (Genoa: Galleria Genova, 1941). Mafai’s Fantasia n. is reproduced in this catalogue.

- See Barbara Cinelli, “Manzù e l’arte sacra: un itinerario complesso,” in Manzù. Dialoghi sulla spiritualità, con Lucio Fontana, ed. Barbara Cinelli and Davide Colombo (Milan: Electa, 2016), 34–39; and Chiara Fabi, “La via del realismo,” in ibid., 56–58.

- See Cesare Brandi, “Una mostra di Manzù,” Le Arti 3 (February–March 1941): 202–04. In the article the critic writes of “bas-reliefs with the two Crucifixions and the two Depositions” (“ I bassorilievi con le due Crocifissioni e le due Deposizioni”) and the relief of the Crucifixion (1940–42, bronze, cm 29.9 x 20) now at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome is reproduced, which he calls Deposizione (Deposition). To reconstruct the story of the press campaign, see Giacomo Maugeri, “Non più spine nel cuore di Manzù,” Omnibus (9 June 1947).

- There are two examples of the relief: one in bronze at the Palazzo del Tau in Pistoia, the other in plaster at the Vatican Museums. A photograph by Peleo Bacci, preserved in the Fototeca of the Marino Marini Foundation, Pistoia, dates the work to 1942. There is also a shot by an unknown photographer, of a variant of the relief without the Picassian horse. Although the work bears the signature “Marino 1939,” the tapped surface around the soldier’s body would point to a much later date, in the mid-1940s. In any case, it would be necessary to examine the signature firsthand to establish its possible date.