The Origins of an Ambiguity: Considerations on the Exhibition Strategies of Metaphysical Painting in the Exhibitions of the Valori Plastici Group, 1921–22

Emanuele Greco Emanuele Greco Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

The magazine Valori Plastici, published in Rome between 1918 and 1922 under the direction of Mario Broglio, had a decisive role in the European artistic context after WWI. It presented the works of an innovative group of Italian artists including Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Giorgio Morandi, Alberto Savinio, Arturo Martini and Edita Walterowna von Zur Muehlen, who worked to rediscover the roots of their own artistic languages in the Italian Medieval and Renaissance traditions. The magazine was a remarkable medium for the international spread of Metaphysical painting, that took place when the artists more connected to this style outdistanced themselves from it in favor of a more naturalistic pictorial language. Moreover, Valori Plastici presented metaphysical painting both as an innovative language of the avant-garde and as well as a language that followed the Italian artistic tradition. The proposal highlights this ambiguous interpretation of Metaphysical painting given by Valori Plastici. Analyzing the exhibition activity of Valori Plastici, with an emphasis on the 1921 tour in Germany, and the participation at the Fiorentina Primaverile in Florence in 1922, it will show how Broglio intended to present Metaphysical painting during the exhibitions of Valori Plastici, and how it was a strategic move to describe the language of Metaphysics to the public in different ways.

Introduction1

One of the most interesting aspects of Metaphysical painting is the difficulty of providing a critical definition of it, and therefore of locating it in twentieth-century art history. As is well known, Metaphysical painting was, for a long period of time, considered by critics in an ambiguous manner: it could be read as an avant-garde movement, or a movement completely in line with tradition.2 Nowadays, we consider Metaphysical painting as an artistic conception close to the historical avant-gardes; nevertheless, in many aspects it is different and parallel, and sometimes even antithetical, to those avant-gardes, in particular Cubism and Futurism. After all, the principal contribution of Metaphysical painting, according to its original definition and realization by Giorgio de Chirico, lies not in the novelty of forms – fully readable in a figurative and traditional sense, and at the same time looking back to the art of the past – but in the novelty of the content, which was given completely new and deep meaning.

It is possible to observe the ambiguity in the definitions of Metaphysical painting already in an early stage, perhaps even in the years when de Chirico was in Paris.3 It becomes, though, more systematically present just after the significant Ferrara season, which attested the work side by side of de Chirico (in Ferrara from 1915 to 1918) and Carlo Carrà (in Ferrara in 1917),4 and spread mainly through the cultural context created around the magazine Valori Plastici. Active between 1918 and 1922, Valori Plastici was the most important means of the diffusion of Metaphysical painting in Italy and internationally, and it was the key means of diffusion of the ambiguous definition of Metaphysical painting as an innovative language as well as a language in line with Italian artistic tradition.

The aim of this text is to highlight, in the context of Valori Plastici, the ambiguity inside the definition of Metaphysical painting. Instead of analyzing the magazine’s contents, the focal point will consider a less studied aspect: the exhibition activities of the Valori Plastici group as promoted by Mario Broglio, the editor of the magazine. This text aims to reconstruct how Broglio intended to present Metaphysical painting to viewers in the several exhibitions of the Valori Plastici group, and it seeks to explain the different ways of, and reasons for, his exhibition strategies for Metaphysical painting.

The magazine Valori Plastici, 1918–22

Valori Plastici, published in Rome between November 1918 and August 1922 (figures 1 and 2) under the direction of editor, painter, critic, and merchant Mario Broglio (1891–1948), had a decisive role in the European artistic context in the years following World War I, in the period defined as retour à l’ordre.5

A group of compelling and innovative artists within the Italian cultural context were united around Broglio, and with their texts as well as their art they participated in the magazine along with activities related to it, such as art editions and exhibitions. Among the most important members of the group were Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Alberto Savinio (the latter was then above all a writer and critic), who had shared a “Metaphysical season” during their stay at Villa del Seminario in Ferrara in 1917. Additional artists who should be counted among Valori Plastici’s associates are Giorgio Morandi, Arturo Martini, and Edita Walterowna von Zur Muehlen – future wife of Broglio. This last group of artists benefited in their individual artistic research from their close contact with Metaphysical painting, which each interpreted according to their own personal sensibilities.

While maintaining a dialogue with the European artistic context,6 Valori Plastici, unlike other magazines of the time, such as La Ronda, did not had a clearly defined program. It intended to propose the theoretical and critical texts as well as artworks, encompassing Metaphysical painting, of its members. Moreover, they sustained to rediscover the roots of their own artistic languages, identified in the Italian Medieval and Renaissance traditions, in particular in the works of Giotto, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio, and Piero della Francesca. As the art historian Maria Grazia Messina has detailed, the magazine Valori Plastici was conceived in the spring of 1918, in the last phase of the World War I, and its first issue was published on November 15, 1918 – not long after the Italian victory proclamation on November 4. Hence, Valori Plastici developed under a climate of “exalted nationalism.”7

The dramatic interruption of the war had brought a change of perspective for numerous artists, for example, Carrà and Ardengo Soffici.8 It made clear that the attention of the Italian artists was no longer focused on Paris and the French contemporary artistic research, but on Italian art and its tradition. There was a need – from a moral perspective – for artists to unite in order to prove the primacy of Italian contemporary art in an international context. The Italian art, renewed in a spiritual manner and validated by the rediscovery of its historical artistic roots, became an ideological reason against the cosmopolitanism that was a key concept of the artistic avant-gardes of which Paris was the “capital” before World War I. Furthermore, as Simona Storchi has stated, the intent of Valori Plastici was militant, and despite the different contents, it followed patterns similar to the avant-gardes in proposing themselves and addressing the public – paradoxically, the same ones Valori Plastici wanted distance from.9

The critical debate in the pages of Valori Plastici had three main branches: modern art, which the artists of the group aimed to redefine in anti-impressionistic and anti-avant-gardist terms; Italian recent tradition, particularly of the nineteenth century; and finally, a more ancient Italian art, especially of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but also, in the last phase of the magazine, of the seventeenth century, related to the concept of “classic” that Valori Plastici sought to elaborate. The first branch, which regarded the redefinition of modern art, includes the reflection of the interpretation and the meaning of the Metaphysical painting of de Chirico and Carrà, which will subsequently lead to assuming the connotation and significance of national painting.

As analyzed by Paolo Fossati,10 the magazine Valori Plastici was an important vehicle for communicating the Metaphysical language internationally, in particular because there were both Italian and French versions of the magazine,11 and also because of the parallel activities of the publishing house Valori Plastici, which continued to realize many important and elegant art monographs ‒ often translated into different languages ‒ even after the end of the magazine (figure 3). Moreover, this diffusion took place during the period where de Chirico and Carrà distanced themselves from the Metaphysical painting for more naturalistic languages.

Metaphysical painting’s definition, or definitions?

From a distance of more than twenty years, in a completely different time period than the one previously mentioned, at the peak of the abstract versus figurative art debate, Mario Broglio wondered about the whole experience of Valori Plastici in a critical text, which was gathered with a selection of his works in the posthumous book Dove va l’arte moderna? (Where does modern art go?, 1950; figure 4). In this text, entitled “Valori Plastici,” Broglio approaches Metaphysical painting and traces some of the characteristics that seem revealing of the interpretation given to the artistic language in the period when the magazine was active.12 It is relevant to mention that Broglio saw Metaphysical painting as a provisional artistic language because of its geometrical stiffness, which was later abandoned for a more “complete” expression that allowed the artists to give more truthfulness to the figures and objects represented. Moreover, the importance of Metaphysical painting was, for Broglio, merely historical; in fact, with Metaphysical painting the artist could, for the first time in recent art, overcome limitations related to more revolutionary trends, in particular Cubism and Futurism, and restore ancient aesthetic principles of the integral and objective representation of nature. For this reason, he defined the associates of Valori Plastici as “the primitives of a new classicism,” able with their works “to generate new impulses, reconnecting with their message a remote past to a distant future and preparing the elements for the restoration of artistic universalism.”13

Broglio’s interpretation of Metaphysical painting was, substantially, the same as that given by Carrà in 1918, which originated from contact with the works of de Chirico: a retrieval of spiritual and formal values such as clarity, pureness of color, and geometric and solid simplification of forms, taken from the Italian Medieval and Renaissance traditions of the Trecento and Quattrocento.14 This constructive and positive interpretation of Metaphysical painting seemed to be favored by the direction of the magazine Valori Plastici, in place of the original interpretation as conceived by de Chirico,15 which was characterized by a stream of philosophical nihilism. For de Chirico, metaphysics consisted of the denial of the thing itself; the denial of every absolute value beyond sensible matter, and therefore the discovery of a “terrible emptiness.”16

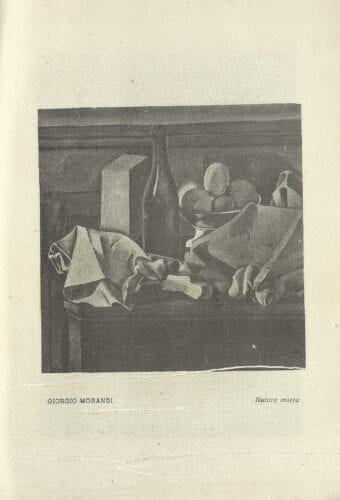

The other artists of Valori Plastici, influenced by Metaphysical painting, seemed to aspire to the more “constructive” interpretation of its language given by Carrà. This was, for example, true of Morandi, who gave a personal version of Metaphysical painting in some of his still lifes. These artworks, created between 1918 and 1919, during his so-called “Metaphysical period,” are characterized by the presence of objects with sharp contours such as mannequins, geometrical solids, and set squares. Around 1920, Morandi started his “post-Metaphysical period,” in which he focused on naturalistic representation.17

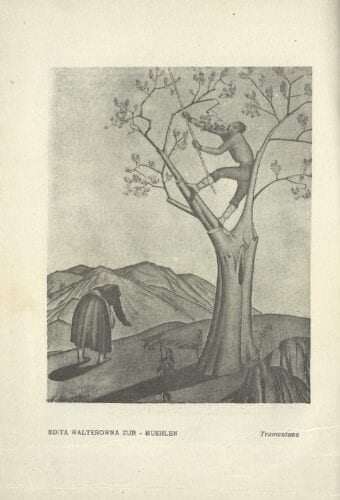

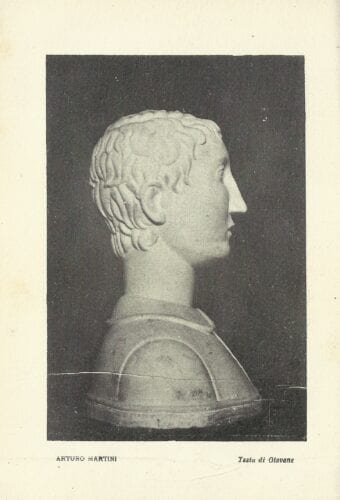

The Metaphysical and post-Metaphysical works of Carrà and Morandi significantly influenced the artistic path of other characters among the Valori Plastici circle, including Edita Walterowna von Zur Muehlen, who, around the 1920s, went from expressionist painting to works of classical balance, as well as stiffness and puristic synthesis (figure 5).18 Likewise, Arturo Martini, passed a key milestone in his artistic path between 1920 and 1921, when in his sculptures he began addressing simple and compact forms that were reduced to elementary plastic and geometrical volumes (figure 6), and this later led him to take input from ancient sculpture.19

The exhibitions of the Valori Plastici group in Germany and Italy, 1921–22

Metaphysical painting was thus considered by Valori Plastici, following the interpretation of Carlo Carrà, as the starting point for the definition of a new Italian artistic language – one deeply connected to the historical roots of the nation, and therefore defined as “modern classicism”20 – and the magazine was the main exponent of this artistic renewal within the nation and internationally. Therefore, it is not surprising that Metaphysical painting was also present in the several exhibitions of the Valori Plastici group, even as this language had already been left behind by the artists – or at least seemed to have been.

The Valori Plastici exhibitions were presented in the final stage of the publication: between the spring of 1921 and the summer of 1922. The last exhibition, which took place in Italy in 1922, marked the closure of the magazine and the artistic environment that was created around it, but it did not mean the end of all activity around Valori Plastici; for example, the publishing house continued under Mario and Edita Broglio’s direction until the beginning of the second postwar period.

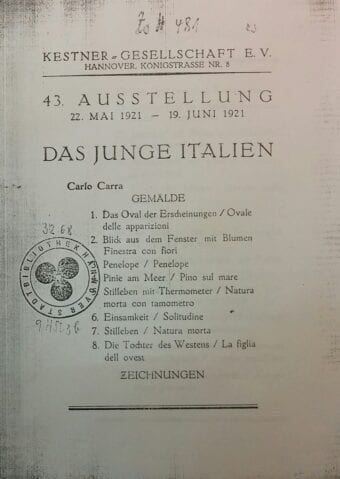

The activities regarding the exhibitions were divided into two connected channels:21 an international one, in Germany during the year 1921; and a national one, in Florence in 1922. The first channel – the longest and most articulated one – consisted of an exhibition that traveled to several German cities, mostly to museums and public arts associations. Named Das junge Italien (The Young Italy), it visited, between the spring and autumn of 1921, the Nationalgalerie in Berlin (April–May; figure 7); the Kestner-Gesellschaft Cultural Association in Hannover (May–June; figure 8); the Hansa Werkstätten Bookshop and Art Gallery in Hamburg and the Vereinigung der Gӧttinger Freunde in Gӧttingen (both in July–August); and finally, the Richter Art Gallery in Dresden (October–November).22

in Berlin, April–May 1921. Photo from Fondo Valori Plastici, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome.

Several motives led Mario Broglio to choose Germany as a stage of the tour; however, the main reason for this decision was that Germany in that period seemed to welcome, more enthusiastically than France and other European countries, the works and contributions of young foreign artists, in particular the Italians. Moreover, Italian art was highly regarded in Germany, where it was associated with concepts of classicism, harmony, and order – those very concepts that Valori Plastici proposed to present.23

The tour featured eight artists: de Chirico, Carrà, Morandi, Walterowna von Zur Muehlen, and Martini, and also Riccardo Francalancia, Roberto Melli, and the French-Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine. Just over two hundred works traveled to Germany – eighty-nine paintings, one hundred and twenty drawings, and eight sculptures – but it is not fully certain which were shown at each location. This is partly due to the varying display arrangements, which were readapted according to the spaces available. Even so, through the recorded list of works it is possible to deduce that the Metaphysical paintings presented on the German tour by the three main exponents of that language – de Chirico, Carrà, and Morandi – were more numerous than works made in different phases.24

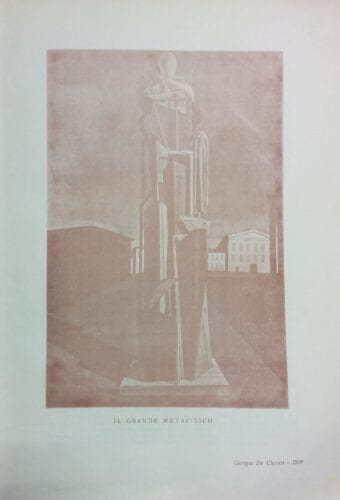

Regarding de Chirico, of his twenty-six paintings25 at least fifteen belonged to the Metaphysical period, in particular from the Ferrara season, including Il trovatore (The Troubadour, 1917), Il grande metafisico (The Great Metaphysician, 1917; figure 9), Ettore e Andromaca (Hector and Andromache, 1918), Le muse inquietanti (The Disquieting Muses, 1918), and five Interno metafisico (Metaphysical Interior, from 1916 to 1918). Additional works on the tour were more recent, and suggested that Metaphysical painting was being replaced by a more classical direction, for example in La vergine del tempo (The Virgin of the Time, 1919), Il ritorno del figliol prodigo (The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1919), Zucche (Pumpkins, 1919), Il tempio di Apollo (The Temple of Apollo, 1920), Autoritratto (Self-portrait, 1920), and Autoritratto su fondo verde (Self-portrait on Green Background, 1920). In these works, especially the ones of the 1920, the painting is lighter and the material technique of Renaissance tempera, which de Chirico discovered at the time, replaces modern oil paint.

As for Carrà, of his nine paintings in the tour26 six belonged to the Ferrara period or near to it, for example Il cavaliere occidentale (The Western Knight, 1917), Solitudine (Loneliness, 1917), Penelope (1917), Natura morta con squadra (Still Life with Square, 1917), L’ovale delle apparizioni (Oval of Apparitions, first version, 1918; figure 10), and La figlia dell’ovest (The Daughter of the West, 1919). From an earlier period, Natura morta (Still Life, also called Composizione TA, 1916–18), confirmed his passage from a Futurist phase into a primitive one, while only two artworks, Finestra e paese (Window and Village, 1921; figure 11) and Il pino sul mare (A Pine by the Sea, 1921), were recent, and attested to his interest in the Medieval and Renaissance language of Italian painters, as well as his recent naturalistic focus.27

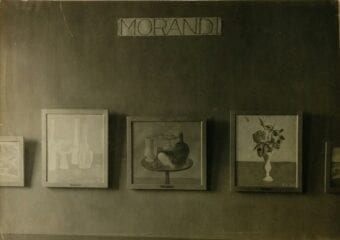

Regarding Morandi, of his twenty-one paintings28 fourteen were from his Metaphysical and post-Metaphysical periods. At least eight of these, each named Natura morta (Still Life), had been realized between 1918 and 1919, during his Metaphysical phase, and others, realized in 1920 – also still lifes – are traceable to the post-Metaphysical period, when the artist seems to have been much more attentive to naturalistic representation. The rest of the traveling works by Morandi were from earlier, including four landscapes – one from 1911, two from 1913, one from 1916 – and a still life from 1916.

The presence of Metaphysical painting, almost unknown in Germany at the time, and never exhibited before,29 did not raise an uproar among German critics. As we know in particular from reviews about the exhibition in Berlin, critics were receptive to Broglio’s presentation of the group of young artists as the most authentic expression of Italian modern art, as well as to the idea that Metaphysical painting represented the starting point of the long and hard artistic path displayed in the exhibition. Additionally, for the most part the German critics’ reviews indicated the works of the Italian primitives of the fifteenth century, especially Piero della Francesca, as the cultural antecedents of the austere, clear, and simple compositions of the young Italian artists.30

After the conclusion of the German tour, at the end of March 1922, a considerable portion of the artworks was sent to Florence for the Fiorentina Primaverile (figure 12), a collective exhibition of more than three hundred artists, which included a room entirely dedicated to works by members of the Valori Plastici group. In contrast to Germany, in Florence Valori Plastici presented itself to the public in a wider and heterogeneous manner. Alongside the original nucleus of the group, other artists participated, most of them Roman friends of Broglio, such as Amerigo Bartoli, Ugo Giannattasio, Cipriano Efisio Oppo, Carlo Socrate (figure 13), Quirino Ruggeri, Armando Spadini (figure 14), and, unofficially, Riccardo Francalancia. Another difference between the Florentine exhibition and the German tour was that the Metaphysical paintings of de Chirico, Carrà, and Morandi were equal or fewer in number than their more recent, naturalistic works.

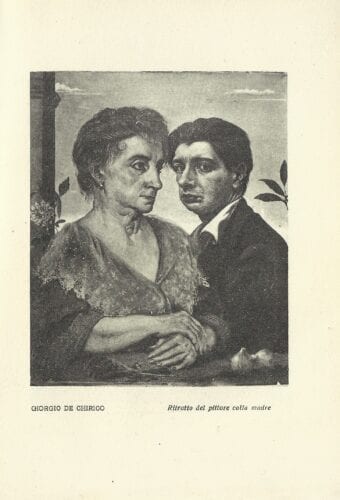

Regarding de Chirico’s thirty-five paintings on display,31 just sixteen belonged to the Metaphysical period, while nineteen were realized between 1920 and 1922. Among the group of Metaphysical pieces were thirteen already shown in Germany, mostly from the Ferrara period; only three artworks were added: L’enigma dell’ora (The Enigma of the Hour, 1910–11), from the beginning phase of Metaphysical painting; an Autoritratto (Self-portrait, 1913), from the Parisian period; and Natura morta con salame (Still Life with Salami, 1919), which can be traced to the transitional period between the Metaphysical and the more naturalistic stages. The group of nineteen recent art pieces was more interesting; just five had been displayed in Germany, and the other fourteen were added to the Florentine stage. Included were very recent portraits and self-portraits, such as Autoritratto con la madre (Self-portrait with Mother, 1921; figure 15), Ritratto della Signora Spadini (Portrait of Mrs. Spadini, 1922), Ritratto della Signora Bontempelli (Portrait of Mrs. Bontempelli, 1922); mythological subjects like Niobe (1920) and Ganimede (Ganymede, 1921–22); sacred personalities like San Giorgio (Saint George, 1920); and also subjects that were not displayed at all in Germany, such as landscapes, for example Paesaggio romano (Roman Landscape, 1921), and small still lifes such as Le rose (The Roses, 1921).

This trend of presenting more recent artworks also applied for Carrà. In fact, to the pieces already displayed in Germany, the artist added three landscapes from 1921:32 Veliero (Sailing ship, also called Marina a Moneglia [Seascape in Moneglia], 1921); and two paintings named Paese (Village) that are not clearly traceable. However, according to the subjects represented, the artworks seemed to belong to a new phase for the artist, characterized by a sort of magical naturalism, that would come more intensely after the end of Valori Plastici. Moreover, these pieces counterbalanced the Metaphysical stream that was so present in the German tour.

A little less significant was Morandi’s case. He presented nineteen paintings in the Florentine exhibition33 – two less than in Germany – most of which had already been displayed there, with a prevalence of Metaphysical (figure 16) and post-Metaphysical paintings. Typical of Morandi in that period, and unlike Carrà and de Chirico, he did not display his newest work; in fact, his most recent pieces in Florence were dated 1920, and represented an already concluded phase, for which de Chirico coined the famous expression “metaphysics of the most common objects.”34

The choice of favoring more recent and naturalistic artworks in the Florentine exhibition encouraged in a positive manner the critical reception of the ex-Metaphysical artists, especially de Chirico. Even if the members of Valori Plastici were criticized for their programmatic ideas, the Metaphysical painting continued to be misunderstood and accused of archaism and intellectual inexpressiveness; some critics, including traditionalist ones, demonstrated an appreciation of the last phases of Carrà and, in particular, de Chirico, who seemed to abandon the Metaphysical language for more naturalistic expression. It was not by chance that de Chirico was the Valori Plastici artist whose work sold best; five works were purchased in Florence, including four recent paintings: Autoritratto (Self-portrait, 1920), San Giorgio (Saint George, 1920), Ritratto della Signora Bontempelli (Portrait of Mrs. Bontempelli, 1922), and a small still life that was unpublished for almost a hundred years, named Pera or Peretta (Pear or Little Pear, 1921).35

Conclusion

In the brief period of Valori Plastici exhibitions, Mario Broglio seemed to attain to the theorized principles published in a short text of 1921, in which he listed two main and different objectives for exhibitions of the group. The first objective, required to the international exhibitions of the group, was to affirm the primacy of Italian art, whose modern identity was embodied by the works of Valori Plastici. The second goal, that regarded the exhibitions on a national level, was much more demanding: in order to affirm and spread the message of the original Valori Plastici group, an active job of recruiting other members (artists) should have been carried out, as actually happened and exemplified in the case of the Florentine exhibition.36

In the aforementioned reception contexts, Broglio followed an exhibition strategy that, among other things, took up the Metaphysical painting of Valori Plastici according to – as discussed above – Carrà’s definition of it. In Germany, where Metaphysical painting was not so diffused, and therefore represented a novelty for the public, it was often presented in a higher proportion with respect to the total number of art pieces displayed by de Chirico, Carrà, and Morandi. In Italy, the situation was completely different: Broglio acknowledged the fact that Metaphysical painting had long been, even before the advent of Valori Plastici, not fully understood. For this reason, in Florence, despite the more open context present in the Fiorentina Primaverile – differently, for example, from the official and more stately Venice Biennale – Broglio chose to highlight the most recent works by the Valori Plastici artists, presenting fewer Metaphysical works as historical evidence of the already concluded phase of de Chirico and Carrà. At this time, Broglio also engaged artists who were not closely related to Valori Plastici, with the objective of enhancing the value and prestige of the ideas proposed by the magazine. Broglio’s intention was not received, however, with much clarity by critics or the general public.

It is interesting to mention that Broglio, in his text on de Chirico for the Fiorentina Primaverile catalogue, provided, for the first time in the Italian critical context, the meaning of Metaphysical painting exactly as de Chirico had intended it. Notwithstanding the adopted definition, Broglio provided contrasting and contrary information: through Metaphysical painting, de Chirico represented, for Broglio, a revolutionary and innovative artist; however, only with the conclusion of this phase, when de Chirico turned to a more traditional and naturalistic expression – that is, during the final period of Valori Plastici – did de Chirico’s paintings became, to Broglio, much more significant and complete.37 This is precisely the kind of ambiguity mentioned at the beginning of the present text. That a traditional channel was preferred and adopted by Valori Plastici was confirmed again by Broglio in the Fiorentina Primaverile catalogue, in his pointing to Carrà’s painting as a model for Italian modern art: “Only from this heroic feeling, tragically Italian, do we believe that the painting has not completely lost the sense of its function, do we hear a voice that admonishes the ease and evanescent vagueness of times.”38

Bibliography

Apollinaire, Guillaume. “G. de Chirico-Pierre Brune.” L’Intransigeant, October 9, 1913.

Apollinaire, Guillaume. “Le Salon des Indépendants-Nouvelle visite aux toiles exposées.” L’Intransigeant, March 3, 1914.

Appella, Giuseppe, Mario Quesada, and Anne-Marie Sauzeau Boetti. Edita Walterowna Broglio. Rome: Leonardo-De Luca, 1991. Exhibition catalogue.

Baldacci, Paolo. “La nazionalizzazione della Metafisica e la nascita delle ‘Piazze d’Italia.’ Note sulla ricezione critica di De Chirico tra il 1912 e il 1919.” In De Chirico, Max Ernst, Magritte, Balthus. Uno sguardo nell’invisibile, by P. Baldacci, Guido Magnaguagno, and Gerd Roos, 49–67. Florence: Mandragora, 2010. Exhibition catalogue.

Baldacci, Paolo, and Gerd Roos. De Chirico a Ferrara. Metafisica e avanguardie. Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2015. Exhibition catalogue.

Benzi, Fabio. “‘Valori Plastici’. Il ritorno all’ordine a Roma.” In Arte in Italia tra le due guerre, 27–44. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 2013.

Broglio, Mario. “Carlo Carrà.” In La Fiorentina Primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze, 41–44. Rome: Casa editrice d’arte “Valori Plastici,” 1922. Exhibition catalogue.

Broglio, Mario. “Giorgio de Chirico.” In La Fiorentina Primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze, 73–76. Rome: Valori Plastici, 1922. Exhibition catalogue.

[Broglio, Mario]. Introduction to the leaflet L’Esposizione di “Valori Plastici” nella Galleria Nazionale di Berlino e la stampa tedesca, post-May 1921.

Broglio, Mario. “Valori Plastici.” In Dove va l’arte moderna?, 41–6. [Rome]: Valori Plastici, 1950.

Carrà, Carlo. “La pittura metafisica a Roma.” Il Popolo d’Italia, June 3, 1918.

Carrà, Carlo. “L’arte di domani” (1918). In Carrà. Tutti gli scritti, edited by Massimo Carrà, 84–86. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1978.

Carrà, Carlo. Pittura metafisica. Florence: Vallecchi, 1919.

Carrà, Massimo, and Vittorio Fagone, ed. Carlo Carrà, Ardengo Soffici. Lettere 1913–1929. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1983.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Giorgio Morandi.” In La Fiorentina Primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze, 153–54. Rome: Casa editrice d’arte “Valori Plastici,” 1922. Exhibition catalogue.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Noi metafisici.” In Scritti/1. Romanzi e Scritti critici e teorici, 1911–1945. Edited by Andrea Cortellessa, 269–76. Milan: Bompiani, 2008. Originally published in Cronache d’attualità, February 15, 1919.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio. Giorgio de Chirico, il tempo di ‘Valori Plastici’ 1918/1922. Roma: De Luca, 1980.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Martini e l’esperienza di ‘Valori Plastici.’” In Arturo Martini. Il gesto e l’anima, edited by Mario De Micheli and Claudia Gian Ferrari, 38–48. Milan: Electa, 1989.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “‘L’uomo più assimilatore che si conosca.’ Martini e l’uso delle fonti visive.” In Filologia del 900: Modigliani, Sironi, Morandi, Martini, 217–60. Milan: Electa, 2013.

Flavio Fergonzi, “Morandi e i quadri degli altri.” In Filologia del 900: Modigliani, Sironi, Morandi, Martini, 161–216. Milan: Electa, 2013.

Fossati, Paolo, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani. Valori Plastici. Geneva-Milan: Skira, 1998.

Fossati, Paolo. “Valori Plastici” 1918–22. Turin: Einaudi, 1981.

Greco, Emanuele. “De Chirico alla Fiorentina Primaverile (1922).” In Origine e sviluppi dell’arte metafisica, 159–208. Milano e Firenze 1909–1911 e 1919–1922, edited by Paolo Baldacci, 159–208. Milan: Scalpendi Editore, 2011. Conference proceedings.

Greco, Emanuele. “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile’ del 1922. Ricostruzione filologica dell’esposizione e del dibattito critico.” PhD diss., Università degli Studi di Firenze, 2018.

Greco, Emanuele. “Un quadro inedito di Giorgio de Chirico ritrovato dopo quasi un secolo. Pera o Peretta del 1921.” Studi OnLine 5, nos. 9–10 (January–December 2018): 70–73.

La Fiorentina Primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze. Rome: Valori Plastici, 1922. Exhibition catalogue.

Lepik, Andres. “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico Italia-Germania.” In Valori Plastici, edited by Paolo Fossati, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani, 155–64. Geneva and Milan: Skira, 1998.

Messina, Maria Grazia. “L’espressionismo nell’area di Valori Plastici.” In L’expressionnisme: une construction de l’autre. France et Italie face à l’expressionnisme/ L’espressionismo: una costruzione d’alterità. Francia e Italia di fronte all’espressionismo, edited by Dominique Jarrassé and Maria Grazia Messina, 61–75. [Le Kremlin-Bicêtre]: Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2012.

Messina, Maria Grazia. “Valori Plastici, il confronto con la Francia e la questione dell’arcaismo nel primo dopoguerra.” In Il futuro alle spalle: Italia-Francia, l’arte tra le due guerre, edited by Federica Pirani, 19–35. Rome: De Luca, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

Mocchi, Nicol M. “Cultura artistica italiana e sfondo politico nel primo dopoguerra (1919–1922): de Chirico e Savinio.” In Origine e sviluppi dell’arte metafisica. Milano e Firenze 1909–1911 e 1919–1922, edited by Paolo Baldacci, 117–29. Milan: Scalpendi editore, 2011. Conference proceedings.

Nicoletti, Luca Pietro. “La ricezione critica di de Chirico tra il 1918 e il 1922.” In Origine e sviluppi dell’arte metafisica. Milano e Firenze 1909–1911 e 1919–1922, edited by Paolo Baldacci, 143–58. Milan: Scalpendi editore, 2011. Conference proceedings.

Pontiggia, Elena. “L’idea del classico. Il dibattito sulla classicità in Italia 1916–1932.” In L’idea del classico 1916–1932. Temi classici nell’arte italiana degli anni Venti, by Elena Pontiggia and Mario Quesada, 9–43. Milan: Fabbri Editori, 1992. Exhibition catalogue.

Presilla, Lucia. “Alcune note sulle mostre di Valori Plastici in Germania.” Commentari d’arte 5, no. 12 (January–April 1999): 51–67.

Rovati, Federica. Carrà tra futurismo e metafisica. Milan: Scalpendi Editore, 2011.

Soffici, Ardengo. “Caffè, Italiani all’estero.” Lacerba, July 1, 1914.

Soffici, Ardengo. “Dichiarazione preliminare.” Rete mediterranea 1, no. 1 (1920): 3.

Storchi, Simona. Valori Plastici 1918–1922. Le inquietudini del nuovo classico. [Reading]: The Italianist, 2006.

How to cite

Emanuele Greco, “The Origins of an Ambiguity: Considerations of the Exhibition Strategies of Metaphysical Painting in the Exhibitions of the Valori Plastici Group, 1921–22,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- This contribution draws on Emanuele Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile’ del 1922. Ricostruzione filologica dell’esposizione e del dibattito critico” (PhD diss., Università degli Studi di Firenze, 2018), in particular with regards to the relation of the several exhibitions of the Valori Plastici group. The author wishes to thank Gerd Roos for his helpful advice.

- Strangely, at the moment there are no studies that systematically address the history of the critical reception of Metaphysical painting. Regarding the critical misfortune of the term “Metaphysics” and the reception of de Chirico’s work during the years of Valori Plastici, see Paolo Baldacci, “La nazionalizzazione della Metafisica e la nascita delle ‘Piazze d’Italia’. Note sulla ricezione critica di De Chirico tra il 1912 e il 1919,” in Paolo Baldacci, Guido Magnaguagno, and Gerd Roos, De Chirico, Max Ernst, Magritte, Balthus. Uno sguardo nell’invisibile (Florence: Mandragora, 2010), 49–67. Some of these ideas are discussed in Luca Pietro Nicoletti, “La ricezione critica di de Chirico tra il 1918 e il 1922,” in Origine e sviluppi dell’arte metafisica. Milano e Firenze 1909–1911 e 1919–1922, ed. Paolo Baldacci (Milan: Scalpendi Editore, 2011), 143–58; and Nicol Mocchi, “Cultura artistica italiana e sfondo politico nel primo dopoguerra (1919–1922): de Chirico e Savinio,” in ibid., 117–29.

- It refers in particular to Guillaume Apollinaire’s interpretation of de Chirico’s work in articles published between 1913 and 1914. Apollinaire wrote of harmonious and mysterious compositions of architectural form, made by de Chirico in meditation following very acute and modern sensations. Even Ardengo Soffici, in his article of July 1914, wrote about de Chirico as a solitary painter in Paris, immersed in calm application, and in love with perspective and geometry like the old master Paolo Uccello. In any case, both Apollinaire and Soffici seem to have considered de Chirico’s painting as an absolutely modern expression. See, in particular, Guillaume Apollinaire, “G. de Chirico-Pierre Brune,” L’Intransigeant, October 9, 1913; and “Le Salon des Indépendants-Nouvelle visite aux toiles exposées,” L’Intransigeant, March 3, 1914. See also Ardengo Soffici, “Caffè, Italiani all’estero,” Lacerba, July 1, 1914. Moreover, according to Baldacci, Soffici’s interpretation is an important element for the reception of de Chirico’s Metaphysical painting in the period of return to order. In fact, Soffici’s text, republished in 1919 in the book Scoperte e massacri, identifies the Metaphysical painting as a style in line with Italian artistic tradition, contributing to the interpretation of Metaphysical painting as a complete opposite to the avant-gardes. See Baldacci, “La nazionalizzazione.”

- For further information regarding this period, see Paolo Baldacci and Gerd Roos, De Chirico a Ferrara. Metafisica e avanguardie (Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2015).

- About the general features of the magazine Valori Plastici, see Paolo Fossati, “Valori Plastici” 1918–22, (Turin: Einaudi, 1981); Maria Grazia Messina, “Valori Plastici, il confronto con la Francia e la questione dell’arcaismo nel primo dopoguerra,” in Il futuro alle spalle: Italia-Francia, l’arte tra le due guerre, ed. Federica Pirani (Rome: De Luca, 1998), 19–35; Paolo Fossati, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani, Valori Plastici (Geneva and Milan: Skira, 1998); Simona Storchi, Valori Plastici 1918–1922. Le inquietudini del nuovo classico ([Reading]: The Italianist, 2006); Fabio Benzi, “‘Valori Plastici’: il ritorno all’ordine a Roma,” in Arte in Italia tra le due guerre (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 2013), 27–44.

- This aspect is evidenced by the presence in the magazine of some foreign collaborators, especially from the French, German, and Dutch cultural contexts. For further information, see Fossati, “Valori Plastici,” 1918–22, 32‒35.

- “Esaltato nazionalismo.” Maria Grazia Messina, “L’espressionismo nell’area di Valori Plastici,” in L’expressionnisme: construction de l’autre. France et Italie face à l’expressionnisme/ L’espressionismo: una costruzione d’alterità. Francia e Italia di fronte all’espressionismo, ed. Dominique Jarrassé and Maria Grazia Messina ([Le Kremlin-Bicêtre]: Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2012), 61. All translations from the Italian are the author’s.

- See, for example, Carlo Carrà, “L’arte di domani” (1918), in Tutti gli scritti, ed. Massimo Carrà (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1978), 84–5. See also the letter from Ardengo Soffici to Carlo Carrà, September 30, 1919, in Carlo Carrà, Ardengo Soffici. Lettere 1913–1929, ed. Massimo Carrà and Vittorio Fagone (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1983), 125; and Ardengo Soffici, “Dichiarazione preliminare,” Rete mediterranea 1, no. 1 (1920): 3.

- Storchi, Valori Plastici 1918–1922, 9. Fossati, in “Valori Plastici” 1918–22, proposes to read the experience of Valori plastici as a reaction, in the name of classicism, to the avant-garde project, whereas Storchi proposes to interpret the magazine as a moment of reflection and re-elaboration of the avant-garde into the theoretical heritage of the avant-garde culture.

- See Fossati, “Valori Plastici,” 1918–22.

- Starting from the second half of 1920, three special numbers of the magazine were published in French under the title Édition pour l’étranger de Valori Plastici ‒ Revue d’Art. Most part of these articles and images were published in the book Le Néoclassicisme dans l’Art Contemporain, edited by the publishing house Valori Plastici in 1923. Regarding the relation between Valori Plastici and the French context, see Messina, “Valori Plastici, il confronto con la Francia.”

- Mario Broglio, “Valori Plastici,” in Dove va l’arte moderna? ([Rome]: Valori Plastici, 1950), 41–46.

- “I primitivi d’un nuovo classicismo […] generare nuovi impulsi, ricollegando con il loro messaggio un remoto passato a un lontano avvenire ed approntando gli elementi per la restaurazione dell’universalismo artistico.” Ibid., 46.

- “Noi che ci sentiamo figli non degeneri di una grande razza di costruttori (Giotto, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio, ecc.)” (Us that we feel like not degenerate sons of a great race of constructors [Giotto, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio, ecc.]). See Carlo Carrà, “La pittura metafisica a Roma,” Il Popolo d’Italia, June 3, 1918, 3. For further information, see also Carrà, Pittura metafisica (Florence: Vallecchi 1919).

- Regarding the deeper interest of Broglio in Carrà rather than de Chirico, see Fossati, “Valori Plastici” 1918–22, 25 and 67.

- “Terribile vuoto.” Giorgio de Chirico, “Noi metafisici,” in Scritti/1. Romanzi e Scritti critici e teorici, 1911–1945, ed. Andrea Cortellessa (Milan: Bompiani, 2008), 272. Originally published as “Noi metafisici,” Cronache d’attualità, February 15, 1919.

- Regarding Morandi’s various periods and research methods, see Flavio Fergonzi, “Morandi e i quadri degli altri,” in Filologia del 900: Modigliani, Sironi, Morandi, Martini (Milan: Electa, 2013), 161–216.

- For an overview of the artist, see Giuseppe Appella, Mario Quesada, and Anne-Marie Sauzeau Boetti, Edita Walterowna Broglio (Rome: Leonardo-De Luca, 1991).

- About Arturo Martini and Valori Plastici, see Flavio Fergonzi, “Martini e l’esperienza di ‘Valori Plastici,’” in Mario De Micheli and Claudia Gian Ferrari, Arturo Martini. Il gesto e l’anima (Milan: Electa, 1989), 38–48. See also Fergonzi, “‘L’uomo più assimilatore che si conosca.’ Martini e l’uso delle fonti visive,” in Filologia del 900, 217–60.

- The concept of moderna classicità (modern classicism), different from tradizionalismo (traditionalism) and nuovo classicismo (new classicism), was proposed by Elena Pontiggia in order to classify the various ideas of the classic during the 1920s in Italy. See Elena Pontiggia, “L’idea del classico. Il dibattito sulla classicità in Italia 1916–1932,” in Elena Pontiggia and Mario Quesada, L’idea del classico 1916–1932. Temi classici nell’arte italiana degli anni Venti (Milan: Fabbri Editori, 1992), 38–43.

- The direct connection between these two exhibitions was recently identified by the author. See Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile,’” 140–212.

- About the exhibitions of Valori Plastici in Germany, see Lucia Presilla, “Alcune note sulle mostre di Valori Plastici in Germania,” Commentari d’arte 5, no. 12 (January–April 1999): 51–67; and Andres Lepik, “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico Italia-Germania,” in Fossati, Rosazza Ferraris, and Velani, Valori Plastici, 155–64.

- See Presilla, “Alcune note,” 51–52.

- The scope of the present text takes into consideration just the number of Metaphysical paintings present in the several exhibitions of Valori Plastici for the following reasons: at the time the paintings were considered more “important” than the drawings; in the two known photos of the exhibitions only paintings can be seen; finally, in the list of works displayed, the titles of the drawings are not always present, therefore it is not possible to identify all of them. The list of the works by the Valori Plastici group in the German tour is first mentioned in Presilla’s essay, and then in Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile’,” 162–71.

- For the German tour, de Chirico presented forty-three artworks: twenty-six paintings and seventeen drawings. See Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile’,” 168.

- For the German tour, Carrà presented twenty-four artworks: nine paintings and fifteen drawings. See Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile’,” 169.

- For more information about Carrà, from Futurism to Valori Plastici, see Federica Rovati, Carrà tra futurismo e metafisica (Milan: Scalpendi editore, 2011).

- For the German tour, Morandi presented forty-one artworks: twenty-one paintings, twelve drawings, and eight watercolors. See Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile,’” 169.

- In Germany, from the end of 1919, some images of Metaphysical artworks by de Chirico, Carrà, or Morandi were diffused among a small group of intellectuals and artists through the magazine Valori Plastici and de Chirico’s monograph published in 1919 by the publishing house Valori Plastici. These images were rarely published in German magazines. The innovative iconography of the Metaphysical pieces was, almost suddenly, a source of stimuli for German artists such as George Grosz and Max Ernst. Nevertheless, only with the exhibition tour of Valori Plastici during 1921 it was possible for a mass public in Germany, for the first time, to appreciate in person the Metaphysical artworks. Regarding the diffusion of Metaphysical painting in Germany before 1921, see Lepik, “Un nuovo Rinascimento,” 157‒58.

- A significant selection of the German press reviews of the Valori Plastici exhibition in Berlin was collected by Mario Broglio in a leaflet conserved in the Valori Plastici Archive at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome. The leaflet is reproduced in Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, Giorgio de Chirico, il tempo di “Valori Plastici” 1918/1922 (Roma: De Luca, 1980), 62–64.

- There were also nine unidentified drawings. Moreover, in Florence there were five paintings that came from the German tour, but were not displayed. See Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile,’” 179. See also Emanuele Greco, “De Chirico alla Fiorentina Primaverile (1922),” in Origine e sviluppi dell’arte metafisica, 159–208.

- There were also some unidentified drawings. See Greco, “La mostra ‘Fiorentina Primaverile,’” 183.

- There were also three unidentified drawings and watercolors. See ibid., 189.

- “La metafisica degli oggetti più comuni.” Giorgio de Chirico, “Giorgio Morandi,” in La Fiorentina Primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze (Rome: Casa editrice d’arte “Valori Plastici,” 1922), 154.

- See Emanuele Greco, “Un quadro inedito di Giorgio de Chirico ritrovato dopo quasi un secolo: Pera o Peretta del 1921,” Studi OnLine 5, no. 9–10 (January–December 2018): 70–73.

- [Mario Broglio], introduction to the leaflet L’Esposizione di “Valori Plastici” nella Galleria Nazionale di Berlino e la stampa tedesca, post-May 1921. Reprinted in Fagiolo dell’Arco, Giorgio de Chirico, 62.

- Mario Broglio, “Giorgio de Chirico,” in La Fiorentina Primaverile, 73–76.

- “Soltanto da questo sentire eroico, tragicamente italiano, noi crediamo che la pittura non ha completamente smarrito il senso della sua funzione, noi sentiamo una voce che ammonisce la facile e caduca vaghezza dei tempi.” Mario Broglio, “Carlo Carrà,” in La Fiorentina Primaverile, 44.