Italienspielerei: Italian and German Painting from Metafisica to Magischer Realismus

Filippo Bosco Filippo Bosco Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

The relationships between Italian pittura metafisica and German Neue Sachlichkeit have mostly been described in two ways: as the “history of an influence,” referring to the knowledge of De Chirico and Carrà among Grosz and other painters working in Munich and Berlin in 1919; or as “similar paths,” pointing out the autonomy of German early objectivity of Davringhausen or Schrimpf. The aim of this paper is to show that the relationship between these two modes of expression is, in fact, biunivocal, underlining figurative intercourses on both sides of their transnational encounter. I will consider the reception of the exhibition “Das Junge Italien” (1921) that showed postwar Italian art in Germany. Theodor Däubler’s writings and the early contributions by Franz Roh recognized how Valori Plastici group was linked to the rising idea of “objectivity” in Germany. Then I will focus on the category of Magic Realism elaborated by Roh in his important 1925 book Nach-Expressionismus, in which Metaphysical artworks play a central role as the roots of many features of the new painting. Many Italian artists were fascinated by metafisica as well as by contemporary German art. This mutual relationship can explain the internal coherence of Roh’s Magischer Realismus, shedding light to the lasting value of Metaphysical international language.

In the catalogue of the 1980–81 epochal exhibition Les réalismes, 1919–1939, the opening essay by Wieland Schmied is dedicated to the “histoire d’une influence”: this phrase conveys the impact of Giorgio de Chirico’s and Carlo Carrà’s paintings on German artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), enabled through the Italian journal Valori Plastici.1 In the exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, Italian pittura metafisica was assigned a central role in interpreting all European realisms and the work of numerous rediscovered artists, including the Italians Felice Casorati, Mario Sironi, and Arturo Martini. That role seems to have since fallen into crisis: not only has the concept of “influence” itself been rejected, as suggested by Michael Baxandall in 1985,2 but also, it seems that nowadays the whole theme of a figurative relationship between German and Italian art in the 1920s remains on the agenda only in Italian historiography and contributions about Giorgio de Chirico’s metafisica and Valori Plastici.3 It is no coincidence that a recent catalogue about the Neue Sachlichkeit avoids discussing its relation to Italian art.4 Moreover, in a 2015 assessment of German artists’ relationship with de Chirico’s painting, they are described as adhering to “a similar path”5 – quite the opposite of “influence.”

This paper goes back to the transnational point of view of Les réalismes, in order to verify the relationship of German and Italian painting and specifically to account for the historical importance of metafisica as the root of a lasting and bi-univocal dialogue between various artists of the two countries throughout the decade of the 1920s.

Italienspielerei: The Early Reception of Italian Art in Germany (1919–21)

As a delicate matter, the “influence” of the Italians Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà was already evident to their contemporaries. The early case of George Grosz is well known:6 at the beginning of 1921, in the avant-garde journal Das Kunstblatt, edited by Paul Westheim, Grosz presented new paintings openly indebted to metafisica. The Italian journal Valori Plastici was then available at the library of Hans Goltz’s gallery in Munich, and Grosz admitted to his knowledge of the new Italian painting. His words reveal a sort of “anxiety of influence”: “In an effort to form a clear, simple style, one involuntarily comes close to Carrà. Nevertheless, everything separates me from him, as he wants to be metaphysically enjoyed and his problem is bourgeois.”7

A few months later, Westheim, who had pointed out this nearness to Valori Plastici in the work of Grosz as well as of Heinrich Maria Davringhausen since 1919,8 hinted at a larger phenomenon of the fortune of Italian painting in Germany, expressing distrust of it: “I think that also the people who here paint like Valori Plastici now – Munich seems especially blessed with them – should be a salutary doctrine. What does this Italiangame [Italienspielerei] prove? A special progression of mastery? Probably not, at best a special stupidity.”9 Italienspielerei is a good term to investigate: it involves a geography, with Munich as a privileged center between Germany and Italy; actors on both sides of the playing field (German and Italian artists and critics); and above all, the reception of Valori plastici.

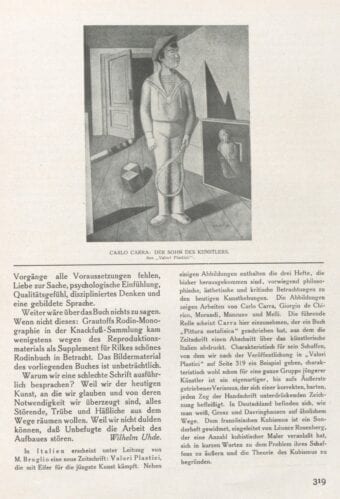

Before the exhibition Das junge Italien (The Young Italians) took place in Berlin in the spring of 1921, the German reception of recent Italian art was based on black-and-white images of Metaphysical paintings. Das Kunstblatt illustrated, in November 1919, the first version of Carrà’s Il figlio del costruttore (The Builder’s Son, 1917–1921; figure 1), intelligently translating the title as Der Kunstlerson (The Artist’s Son). Then, in the spring of 1920, the avant-gardist leaflet Der Ararat, printed in Munich by Goltz, reproduced paintings and a drawing by de Chirico along with Carrà’s Le figlie di Lot (Lot’s Daughters, 1919).10 In April 1920, Theodor Däubler published an update of the prestigious art revue Der Cicerone on recent Italian art, with illustrations of a number of de Chirico’s Metaphysical compositions, a sculpture by Roberto Melli, and Carrà’s Il cavaliere occidentale (The Western Horseman, 1917).11 Däubler’s article provides notes on de Chirico’s mannequins, which compare them to “the homunculus, which is an entity, not a doll, which bursts forth from eternity, although it was bound to shatter beneath us.”12 German avant-gardists and Dadaists such as Grosz and Rudolph Schlichter clearly paid attention to this anthropologic estrangement in their direct and explicit references to de Chirico’s and Carrà’s iconography.

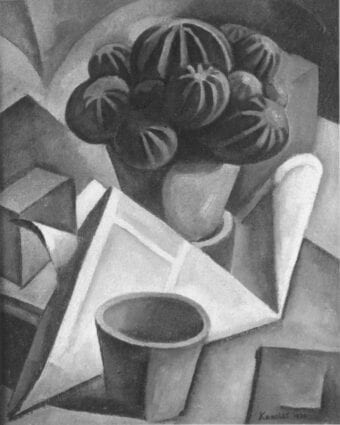

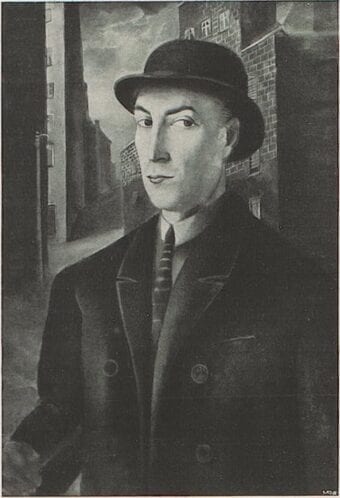

Other artists demonstrated interest in the “return to craft” expressed programmatically by many contributors to Valori plastici.13 The late Expressionist Frankfurt painter Hermann Lismann, who lived in Italy at the beginning of the century, probably came across the journal between 1919 and 1920. In a 1920 self-portrait (figure 2), his transition to a rhetoric of museum tradition can be observed: a reproduction of Giotto’s fresco Saint Francis’s Speech to the Birds hangs in the depicted atelier, and the intellectual self-presentation is drawn from Nicolas Poussin via Giorgio Morandi and de Chirico – specifically images by the latter pair already published in Valori plastici.14 On a formal level, an interest in the newly classical volumetric synthesis of Italian art can be seen in Alexander Kanoldt’s work: living in Munich and often traveling to Italy, he was likely fascinated by the simplified chiaroscuro of Morandi’s still lifes with relation to his post-Cubist compositions (figure 3). In accordance with this tendency, “clarity, simplicity, strictness, the idea of a new classicism”15 were the qualities that announced, in 1921, in the pages of Das Kunstblatt, the conversion of Ardengo Soffici to the new Mediterranean classicism of Italian modern art.

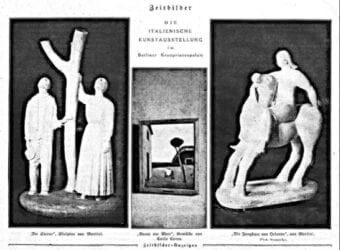

Reviews of the exhibition Das junge Italien show how actual encounter with these paintings, sculptures, and drawings changed or confirmed the tendencies of the Italienspielerei.16 Germans could finally see de Chirico’s colors, which were “rich in a mysterious, magic brightness toward a mystic nostalgia of last things.”17 His classical paintings, such as Il ritorno del figliol prodigo (The Prodigal Son, 1919), which also recalls Jacques Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii (1784),18 and his neo-Renaissance portraits were appreciated as going beyond the too intellectual features of metafisica. Carrà was already overtaking de Chirico in gaining the favor of the German public, while his typical Giotto-esque synthesis, “mostly set to gray,” was becoming no longer based in the “mechanical decomposition of the human figure,” but rather, in simplicity. The success of Pino sul mare (Pine by the Sea, 1921), with its “monumental simplification of the surfaces,”19 is proved by the fact that it is the only painting captured in the photographs of the exhibition taken by Robert Sennecke (figures 4–5).

In them, Arturo Martini’s sculptures draw the greatest attention, and many reviewers easily recognized their affinity with the works of the German sculptor Ernst Barlach.20 Commentary on Morandi’s works focused on their peculiar chromatic structure:

Especially his still lives, that mix Cézanne’s synthesis with the simplified schemes of the modern Italians, have an extraordinary softness in the chromatic values, which are graduated and contrasted to each other with a highly cultivated sensibility. It is exquisite the way he gently attunes gray and rose, building a whole painting tone on tone.21

In 1921, in the militant criticism on contemporary art, it was already possible to trace an important Italian function more serious and important than Westheim’s expression Italienspielerei would suggest. In 1920, Willi Wolfradt called Georg Schrimpf “the most Italian” (italienischsten) among German artists, for his “consistently thin, linear, metallically harsh-silhouetted drawing” and “local-colored fast-paced painting.”22 In the aftermath of Das junge Italien, Fritz Stahl linked the early post-Cèzanne objectivity of Richard Seewald or Max Unold to Valori plastici through the Pierfrancescan figure of the “really egg-shaped egg.”23 These and other “Italian-like” artists exhibiting in late 1921 in Munich and Berlin played a role in the so-called “crisis” of Expressionism, which reflected both the political suppression of the revolutionary instances as well as the exhaustion of the poetics promulgated by Der Sturm.24 In the words of Franz Roh, the “internal drawing, cooling, sharpness of objects” of these new painters had overtaken colorful, distorted Expressionist paintings, and it was “clear from such artists why the countermovement of Carrà and comrades became necessary.”25

The Italian Function in Franz Roh’s Magischer Realismus

Franz Roh was then a thirty-one-year-old scholar based in Munich, who had recently published his dissertation on seventeenth-century painting in the Netherlands. From 1916 to 1919 he had been the assistant of the famous professor Heinrich Wölfflin: Roh inherited from his mentor the system of binary categorization to describe historical changes in style,26 and he used a similar theoretical approach in the analysis of contemporary art. In commenting on Dutch old masters, he relied on Wölfflin’s definition of linear and painterly styles in demonstrating an early interest in the features of objective realism:

The relationship of the autonomy of all the parts of the painting […] is based on the fact that things are deduced less and less from their tactile and plastic content and one tends to perceive them mostly by the tonal value. […] This also has an anthropological implication, in the fact that the value of the isolated frontal figure typical of the sixteenth century now often diminishes in favor of an impersonal setting, so to speak more modest, of man in the set of objects.27

And yet, a little further on, this text contains a description of the “Netherlandish spirit”: “his indulgent gaze on reality, his contemplative passivity, had to be successful in this dedication to things […] without magniloquence, introverted, letting things speak for themselves.”28

From 1921 to 1923, Roh went on systematizing his comments on ancient and contemporary art in an important, book-length essay, Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus (Post-Expressionism – Magic Realism), which he published in 1925.29 It is interesting to notice that in his review of the book, Westheim did not appreciate it as an early historicization, and rather played down, once more, the importance of the Italienspielerei: “I have the impression that Roh overestimated the meaning of Valori plastici both as stimulus and value.”30

“Only with the Italian group of Valori plastici, Carrà, and de Chirico do we enter the core of our movement,”31 reads Roh’s treatise, referring to the new formal values of pure geometrical abstraction dropped into a classical naturalism. Elsewhere, he refers to Carrà’s monograph on Georg Schrimpf as a historical example of the “interrelation” (Zusammenhang) between German and Italian painting.32 This book, published in 1924 by the Valori Plastici publishing house, does not adequately evidence the Italian interest in contemporary German art: Carrà reused large excerpts of his long article “Misticismo e ironia nella pittura contemporanea” (Mysticism and Irony in Contemporary Painting, 1921) in reading Schrimpf’s paintings as ex post confirmation of the European impact of Carrà’s own poetics.

Strong ties did exist between German painting and Italian artists from 1921 to 1925, which have been underestimated in historiography about Italian realism in the 1920s.33 Seamlessly compared to the prewar period, access to knowledge of German art was possible through the illustrated journals that widely circulated in libraries and cultural clubs.34 Many Italian artists were fully aware of the foreign tendencies, and even when they affirmed a return to their own tradition, they did so by confronting a rich visual panorama on European art. Such transnational exchanges demonstrated the internal coherence of Roh’s analysis and the historical pertinence of the Magischer Realismus formula.

German Visual Sources for Italian Painters: Some Cases of the 1920s

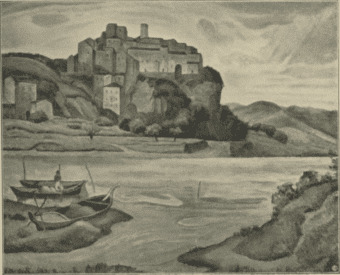

Roh described a new interest in Italian landscape and the phenomena of a sort of modern Grand Tour, which resulted in a “new Nordic interpretation of Italy [that shapes] the way the young generation will feel about the classical country for some time.”35 Of the views of central Italy’s villages – for example San Gimignano, Olevano, Bellegra, or Subiaco – early realized by Kanoldt in his travels, this descriptive interpretation gives a sense of spiritualization and coolness (figure 6).36

One year before Roh’s Magischer Realismus volume was published, Guido Lodovico Luzzatto, the Italian critic who was most informed on Germany, noticed similarly that “Assisi, severe and sweet, has become the Mecca of the new German landscape.”37 He explained this tendency in the light of the critical economic situation of postwar Germany and the need for mystic evasion. Through many illustrated art journals, a painter with a German formation such as Raffaele De Grada, who had moved to San Gimignano in 1921, could well have known of this successful German trend: he seemed to repurpose it in his most monumental and evocative landscapes of the early 1920s (figure 7).

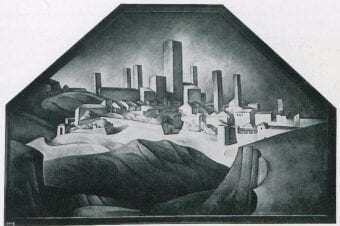

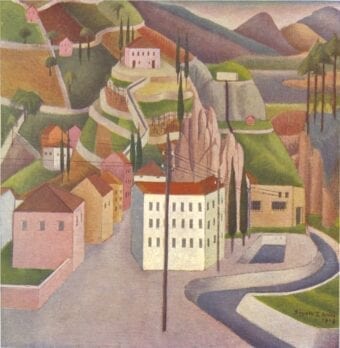

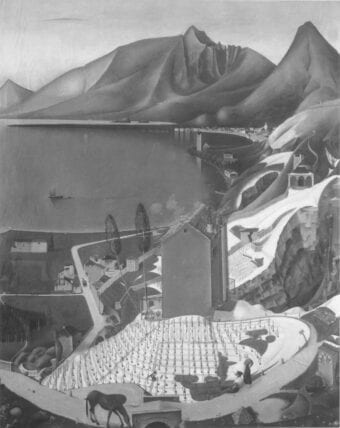

Spatial description is assigned a new feature in Roh’s argumentation, according to which “the very close is confronted with the far away” in a “clarified way, frank,”38 anti-atmospheric, and anti-impressionistic, with visual sources in landscapes of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Remote distance and miniaturistic description characterize the archaistic landscapes of Gigiotti Zanini from 1919 (figure 8).

As a German speaker living in Trento, he likely knew the work of the young Swiss artist Niklaus Stoecklin, who was influenced early on by de Chirico’s work and in 1918 exhibited, in Zurich, Casa Rossa (The Red House, 1917); as a surprising case of precisionism, the July 1918 issue of Das Kunstblatt also reproduced this work (figure 9).39

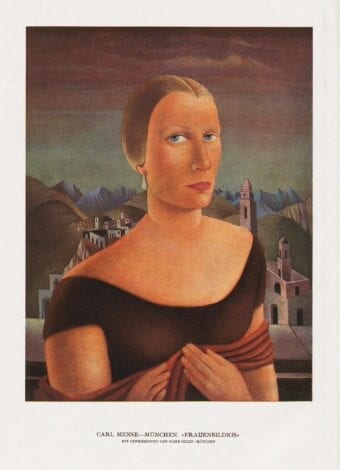

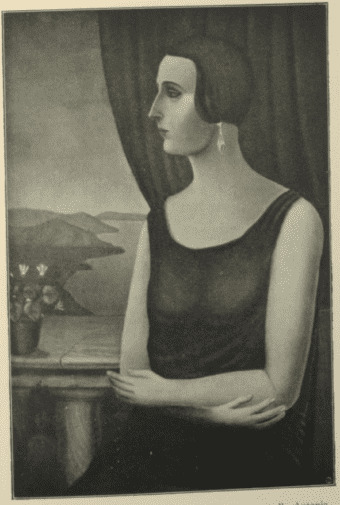

This typically German taste for relentless optical focus, coolness in the description of details, and the impassivity and isolation of figures determined also the rediscovery of certain old masters. Ubaldo Oppi, a German-speaking Italian artist who moved from Paris to Milan in 1922, clearly modeled his portraiture of the 1920s on Renaissance examples (figure 10); nevertheless, his peculiar insistence on the coldness of tactile details followed from contemporary German portraitists. Works by the Munich painter Carlo Mense were often illustrated in journals such as Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, which were widely available in Italian libraries (figures 11–12).40

This typical taste for objectivism based on the coeval German painting spread in the 1920s; for example, there was trace of it in much of the portraiture shown in the two Milanese Novecento Italiano exhibitions (1926 and 1929),41 organized by the art critic Margherita Sarfatti, where it emerged clearly in the work of an Oppi’s follower, the Vicentine artist Pierangelo Stefani (figure 13). An analogue triangulation between old masters, German contemporary painting, and Italian Magical Realist artworks explains the interest of the Venetian painter Cagnaccio di San Pietro in Otto Dix’s most Dürer-like paintings (figure 14); he portrayed his daughter Liliana with the same calligraphic precisionism (figure 15).42

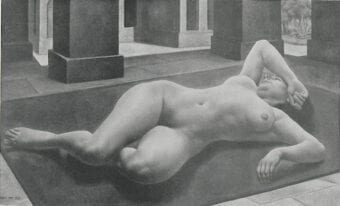

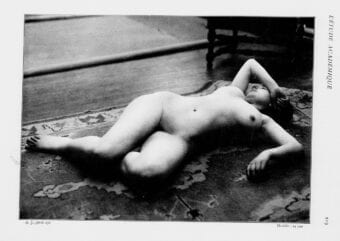

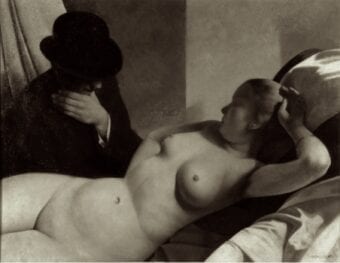

In Roh’s book, an entire chapter is dedicated to the new sensibility of photography, which painters adopted in a fresh “aesthetic of fragmentation opposed to that of the organic;”43 such painters were literally magnifying photographs and only slightly retouching them in constructing a composition. This was exactly the case with Oppi’s nudes, which were all directly based on pictures from a Parisian vintage publication, and they provoked a scandal and much debate in 1926, when many critics condemned Oppi’s practice as a mere mechanical copying.44 Roh’s precious analysis is then valid also for Nudo disteso (Lying Nude, 1925; figure 16): the chiaroscuro, exactly carried over from the photograph (figure 17), gives a peremptory quality to the figure, as cropped from the foreground and sharply outlined.

A Metaphysical Revival: Italian Painting Exhibited in Germany

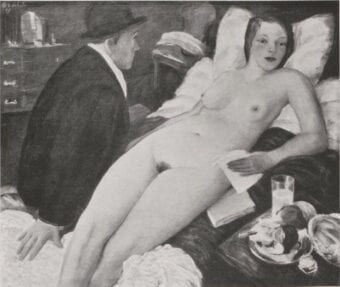

It is no coincidence that Nudo disteso was exhibited at the first great international art show in Germany after the First World War, the 1926 International Kunstausstellung Dresden. The small Italian section, in representing the avant-garde direction of Italian modern art, demonstrated how already influential was Roh’s Magischer Realismus.45 Starting with two Parisian works by Amedeo Modigliani and Gino Severini’s Futurist Bal Tabarin (Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, 1912), the director of the Dresden Museums Hans Posse then gave a central role to de Chirico’s metafisica, with three loans from Giorgio Castelfranco’s collection, including The Prodigal Son and The Disquieting Muses, which Däubler had discussed in 1920 in Der Cicerone.46 The youngest generation was represented only by Oppi and Casorati; they were commented upon as the most “objective” (sachlich) among the Italians, and eloquently compared to German artists including Kanoldt.47 One of the three works by Casorati exhibited on that occasion, Conversazione platonica (Platonic Conversation, 1925), is an ideal example of how bi-univocal the figurative dialogue had become by then (figure 18): its fascinating model is recognizable in those German paintings of the following years in which the silent encounter between a fully dressed bourgeois and a nude female becomes a daily narrative, as in Oskar von Schab’s Bespräch (Conversation, 1928; figure 19), or erotically disturbing, perhaps, as in Hermann Sohn’s Paar (Couple, 1928; figure 20).

In 1928, Roh himself was asked to organize an exhibition about Italian “Nachexpressionistische Malerei” at the Leipziger Kunstverein,48 and he commented upon and illustrated his choices in an article published in the important journal Die Kunst für Alle.49 He was particularly eloquent in addressing his differences with Margherita Sarfatti’s assessment of the Novecento movement, then establishing itself as the label for national Italian painting.50 For instance, he renounced works by Sironi, her favorite artist, and insisted on requesting artworks not always recent, in order to provide intelligent comparisons of figurative attention and historical openness.

Carrà appeared once more as the fundamental key of Roh’s interpretation. In the exhibition itself, his vivid influence on younger generations was evident, for instance in paintings by Alberto Salietti. In the mid-1920s, Carrà’s works experienced a renewed reception in Germany. In 1925, Worringer praised the Pine by the Sea after seeing it in a 1924 color reproduction of the Berlin Photographic Society.51 In the same year, recent paintings by Italo Tavolato were published in an article about Futurism in Das Kunstblatt.52 In 1929, his painting I funerali dell’anarchico Galli (Funeral of Anarchist Galli, 1910–11), then in the collection of Dr. Albert Borchardt, was exhibited at the Juryfreie Kunstschau in Berlin in a gallery featuring the left-wing Novembergruppe – in striking opposition to the room occupied by the Fascist Novecento.

Roh’s 1928 choice of such Metaphysical masterpieces as Carrà’s L’ovale delle apparizioni (The Oval of the Apparitions, 1918), Natura morta metafisica (Metaphysical Still Life, 1919), and La figlia dell’Ovest (The West Daughter, 1919) brought them again to Germany, after 1921, and Mio figlio (My Son, 1919) was reworked by the artist for the occasion. Among the illustrations in the article appears Lot’s Daughters and other Italian paintings closely linked to Valori plastici: Oppi’s Pomeriggio autunnale (Autumnal Afternoon, 1922) and Il cieco (The Blind, 1922); 1921 miniaturistic paintings by Zanini; and the only painting chosen by Roh from Casorati’s studio, Silvana Cenni (1922). In this last image, later nicknamed “virgo metaphysica millenovecentoventidue”53 (“1922 Metaphysical virgin”), Roh might easily have recognized a foreground of volumes indebted to Morandi’s Metaphysical still lifes as well as the artist’s affinity with Piero della Francesca – which he had pointed out three years before.

Conclusion

This German point of view on Italian Magical Realism of the 1920s sheds light on the historical meaning of the “influence” described by Wieland Schmied in 1980 and reformulated on the basis of transnational inquiry. It accounts for a long-lasting dialogue across the Alps that was often ignored or rejected by coeval Italian critics and in the chauvinist rhetoric of Sarfatti’s Novecento Italiano. Firstly, at the beginning of the decade, the Italienspielerei and the German reception of metafisica determined the relationship between painters from the two countries to be bi-univocal and taking place through a common language of apparently extremely fertile figurative exchange. Secondly, the formalist analysis offered by Franz Roh in Magischer Realismus and later writings represents an extraordinarily productive frame for reconstructing actual points of contact among European artists. Roh also had an historical role in collocating metafisica at the core of the European realism in exhibitions of the late 1920s and in their retrospective interpretation. The third and last moment of this parabola concerns how recent Italian painting was exhibited in Germany: instead of being the banner of a nationalistic return to tradition, works by Casorati, Oppi, and Zanini were ascribed to the European modern movements of post-Expressionism and Magical Realism. Metaphysical paintings dating to almost ten years later by Giorgio de Chirico and, above all, Carlo Carrà – already fixed in the canon of the klassische Moderne – served to remark upon this avant-gardist root of modern realist painting.

Bibliography

Baxandall, Michael. Patterns of Intention: In the Historical Explanation of Pictures. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985.

Bossaglia, Rossana. Il Novecento Italiano. Storia, documenti, iconografia. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1979.

Braun, Emily. “Franz Roh: Tra postespressionismo e realismo magico.” In Realismo magico. Pittura e scultura in Italia 1919–1925, edited by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, 57–64. Verona: Galleria dello Scudo; Milan: Mazzotta, 1988. Exhibition catalogue.

Carrà, Carlo. Georg Schrimpf. Rome: Valori Plastici, 1924.

Catalogo della prima mostra del Novecento italiano. Febbraio–Marzo 1926. Milan: Gualdoni, 1926. Exhibition catalogue.

Corwegh, Robert. “Hermann Lismann.” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration 45 (1919–20): 270–73.

Cremona, Italo. Felice Casorati. Turin: Accame, 1942.

Dal Canton, Giuseppina. “La cultura figurativa di Cagnaccio.” In Cagnaccio di San Pietro, edited by Renato Barilli, 23–24. Venice: Museo Correr; Milan: Electa, 1991.

Dälberg, Franz. “Aus dem Kunstleben Berlins – Italienische Jugend.” Hannoverscher Courier, April 20, 1921.

Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 10 (October 1921): 318.

Däubler, Theodor. “Neueste Kunst in Italien.” Der Cicerone 12, no. 9 (April 1920): 349–55.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Il ritorno al mestiere.” Valori Plastici 1, nos. 11–12 (November–December 1919): 15–19.

Der Ararat 1, no. 4 (January 1920).

Der Ararat 1, no. 7 (April 1920).

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio. Realismo Magico. Pittura e scultura in Italia, 1919–1925. Verona: Galleria dello Scudo; Milan: Mazzotta, 1988.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio. “‘Valori Plastici’ eine Zeitschrift, ein Verlag, eine Kunstlrgruppe und der Ordnungsruf.” In Mythos Italien. Wintermärchen Deutschland. Die italienische Moderne und ihr Dialog mit Deutschland, edited by Carla Schulz-Hoffmann, 59–64. Munich: Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen and Prestel Verlag, 1988.

Fochessati, Matteo, and Gianni Franzone, eds. Anni venti in Italia. L’età dell’incertezza. Genoa: Sagep Editori, 2019. Exhibition Catalogue.

Fuhrmeister, Christian. “Hartlaub and Roh: Cooperation and Competition in Popularizing New Objectivity.”. In New Objectivity: Modern German art in the Weimar Republic, edited by Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, 40–49. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2015. Exhibition catalogue.

Gankse, Willi. “Junge italienische Kunst in der Nationalgalerie.” Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, April 8, 1921.

Gerster, Ulrich. “‘Un percorso analogo.’ Genesi e sviluppo della Nuova Oggettività.” In De Chirico a Ferrara. Metafisica e avanguardie, edited by Paolo Baldacci, 153–63. Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2015. Exhibition catalogue.

Grohmann, Will. “Die Kunst der Gegenwart auf der Internationalen Kunstausstellung Dresden 1926.” Der Cicerone 18, no. 12 (June 1926): 375–416.

Grosz, Georg. “Zu meinen neuen Bilder.” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 1 (January 1921): 10–16.

Internationale Kunstausstellung Dresden 1926 June–September. Dresden: Jahresschau Deutscher Arbeit, 1926. Exhibition catalogue.

Lepik, Andres. “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico Italia-Germania.” In Valori Plastici. XIII Quadriennale, edited by Paolo Fossati, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani, 155–64. Milan: Skira, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

Lüthgen, Eugen. “Carlo Mense. München.” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration 50, no. 25 (May 1922): 58–66.

Luzzatto, Guido Lodovico. “Rassegna d’arte. La Nuova Secessione di Monaco. Soggetti e ispirazioni italiane in pittori tedeschi.” Rivista d’Italia 27, no. 1 (February 1924): 252–56.

März, Roland. “Republikanische Automaten. George Grosz und die Pittura Metafisica.” In George Grosz. Berlin, New York, edited by Peter-Klaus Schuster, 148–56. Berlin: Neue Nationalgalerie and Ars Nicolai, 1994. Exhibition catalogue.

Ferrari, Daniela, Danka Giacon, Anna Maria Montaldo, and Antonello Negri, eds. Margherita Sarfatti. Rovereto: Il Museo d’Artre Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (MART); Milan: Museo del Novecento; Milan: Electa, 2018. Exhibition catalogue.

Messina, Maria Grazia. “L’espressionismo nell’area di Valori Plastici.” In L’expressionnisme. Une construction de l’autre, edited by Dominique Jarrassé and Maria Grazia Messina, 61–75. Le Kremlin Bicêtre: Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2012.

Müller-Scherf, Angelica. “Klassizismus und Realismus im Werk von Edmund und Alexander Kanoldt.” In Alexander Kanoldt: 1831–1939. Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Lithographien, edited by Michael Koch, 11–27. Waldkirch: Wladkircher Verlag-Gesellschaft, 1987. Exhibition catalogue.

Mocchi, Nicol. “Il modello austro-tedesco per i pittori italiani negli anni del Simbolismo. Qualche ipotesi di ripresa visiva.” Prospettiva, nos. 165–166 (January–April 2017): 142–65.

Osborn, Max. “Moderne Italiener in Berlin.” Vossische Zeitung, April 1, 1921.

Pontiggia, Elena. “Lipsia 1928. Roh e il Novecento Italiano.” Storia dell’arte, nos. 13–14 (2006): 269–77.

Pontiggia, Elena. Modernità e classicità. Il ritorno all’ordine in Europa, dal primo dopoguerra agli anni Trenta. Milan: Mondadori, 2008.

Presilla, Lucia. La mostra di Valori Plastici a Berlino e la sua fortuna. Masters thesis, Università di Perugia, 1997–98.

Presilla, Lucia. “Alcune note sulle mostre di Valori Plastici in Germania.” Commentari d’arte 5, no. 12 (2000): 51–67.

Roh, Franz. “Ausstellungen. München.” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 10 (October 1921): 318–19.

Roh, Franz. “Bemerkungen zur nachexpressionistischen Malerei Italiens.” Die Kunst für Alle 43 (1927–28): 168–80.

Roh, Franz. Hollandisce Malerei. Jena: Eugen Diederich, 1921.

Roh, Franz. Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus. Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1925.

Schmied, Wieland. “L’histoire d’une influence. ‘Pittura metafisica’ et ‘Nouvelle Objectivité.’” In Les réalismes, edited by Pontus Hultén, Gérard Régnier, and Jeanne Bouniort, 20–25. Paris: Centre Pompidou; Berlin: Staatliche Kunsthalle, 1980. Exhibition catalogue.

Seconda mostra del Novecento italiano. Catalogo. 2 marzo – 30 aprile 1929. Milan: Gualdoni, 1929. Exhibition catalogue.

Stahl, Fritz. “Seniorenprüfung. Ausstellung der Berliner Sezession.” Berliner Tageblatt, October 29, 1921.

Tavolato, Italo. “Chronik der futuristischen Instauration.” Das Kunstblatt 9, no. 6 (June 1925): 354–65.

Vögele, Christoph. Niklaus Stoecklin und die neue Sachlichkeit. PhD diss., Universität Zürich, 1993.

Washton Long, Rose-Carol, and Stephanie Barron, eds. German Expressionism: Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National Socialism. New York: Hall, 1993.

Westheim, Paul. Das Kunstblatt 3, no. 11 (November 1919): 319.

Westheim, Paul. “Kunst in Frankreich.” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 12 (December 1921): 8–25.

Westheim, Paul. “Nach-Expressionismus.” Berliner Börsenzeitung, January 22, 1926.

Wölfflin, Heinrich. Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Das Problem der Stilentwickelung in der neueren Kunst. Munich: Bruckmann, 1915.

Wolfradt, Willi. “Austellungen.” Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 3 (March 1920): 93–94.

Worringer, Wilhelm. “Carlo Carrà’s ‘Pinie am Meer’. Bemerkungen zu einem Bilde.” Wissen und Leben 27, no. 18 (1925): 1165–69.

How to cite

Filippo Bosco, “Italienspielerei: Italian and German Painting from Metafisica to Magischer Realismus,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- See Wieland Schmied, “L’histoire d’une influence. ‘Pittura metafisica’ et ‘Nouvelle Objectivité,’” in Les réalismes 1919–1939, ed. Pontus Hultén, Gérard Régnier, and Jeanne Bouniort (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou; Staatliche Kunsthalle, Berlin: Staatliche Kunsthalle, 1980), 20–25. The exhibition was on view at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National de l’Art moderne, Paris, from December 17, 1980–April, 20, 1981, and at the Staatliche Kunsthalle, Berlin, from May 10–June 30, 1981.

- See Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 58–62. Baxandall stressed the active role of the “influenced” side of any stylistic encounter, consequently inverting the relationship between sources and artists and criticizing the deterministic function often assigned to models.

- Some examples are Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, “‘Valori Plastici’ – eine Zeitschrift, ein Verlag, eine Kunstlergruppe und der Ordnungsruf,” in Mythos Italien. Wintermärchen Deutschland. Die italienische Moderne und ihr Dialog mit Deutschland, ed. Carla Schulz-Hoffmann (Munich: Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen and Prestel Verlag, 1988), 59-64; Andres Lepik, “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico Italia-Germania,” in Valori Plastici. XIII Quadriennale, ed. Paolo Fossati, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani (Milan: Skira, 1998), 155–64; Maria Grazia Messina, “L’espressionismo nell’area di Valori Plastici,” in L’expressionnisme. Une construction de l’autre, ed. Dominique Jarassé, Maria Grazia Messina (Le Kremlin Bicêtre: Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2012): 61–75.

- Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, eds., New Objectivity. Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic 1919–1933 (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2015).

- Ulrich Gerster, “‘Un percorso analogo.’ Genesi e sviluppo della Nuova Oggettività,” in De Chirico a Ferrara. Metafisica e avanguardie, ed. Paolo Baldacci (Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2015), 153–63.

- See Roland März, “Republikanische Automaten. George Grosz und die Pittura Metafisica,” in George Grosz. Berlin, New York, ed. Peter-Klaus Schuster (Berlin: Neue Nationalgalerie and Ars Nicolai, 1994), 148–56.

- Georg Grosz, “Zu meinen neuen Bilder,” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 1 (January 1921): 11. Introducing Grosz’s article in his own journal, Westheim highlighted this stylistic nearness: “The series of new paintings by Grosz, that we publish, shows the artist in a new phase of development, that has dragged him near Carrà, as Grosz himself confesses.” All translations into English are the author’s.

- Introducing Valori Plastici’s aesthetics, Paul Westheim wrote: “Characteristic of this whole group of younger artists is a singular, extreme Verism which applies a correct, hard drawing suppressing any individual style. In Germany, as one knows, George Grosz and Heinrich Davringhausen are on the same road.” Das Kunstblatt 3, no. 11 (November 1919): 319.

- Paul Westheim, “Kunst in Frankreich,” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 12 (December 1921): 358.

- See Der Ararat 1, no. 4 (January 1920): 11, 16; and Der Ararat 1, no. 7 (April 1920): 51.

- Theodor Däubler, “Neueste Kunst in Italien,” Der Cicerone 12, no. 9 (April 1920): 349–55.

- Ibid., 353.

- See, for example, Giorgio de Chirico, “Il ritorno al mestiere,” Valori Plastici 1, nos. 11–12 (November–December 1919): 15–19.

- A trace on the rhetoric of the atelier appears also in coeval comments on Lismann’s work. In his studio, “often there’s a little sketch apparently inconsequential, a photograph on the wall betrays to which past the artist feels connected, and books unravel his inclinations.” Robert Corwegh, “Hermann Lismann,” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration 45 (1919–20): 271.

- Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 10 (October 1921): 318.

- For a complete analysis of reviews of the exhibition, see Lucia Presilla, “La mostra di Valori Plastici a Berlino e la sua fortuna” (Masters thesis, Università di Perugia, 1997–98); and “Alcune note sulle mostre di Valori Plastici in Germania,” Commentari d’arte 5 (2000), no. 12: 51–67. I am grateful to Professor Presilla for sharing with me her unedited research.

- Willi Gankse, “Junge italienische Kunst in der Nationalgalerie,” Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, April 8, 1921.

- Franz Dälberg, “Aus dem Kunstleben Berlins – Italienische Jugend,” Hannoverscher Courier, April 20, 1921.

- Ganske, “Junge italienische Kunst.”

- Ibid.

- Max Osborn, “Moderne Italiener in Berlin,” Vossische Zeitung, April 1, 1921.

- Willi Wolfradt, “Austellungen,” Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 3 (March 1920): 94.

- Fritz Stahl, “Seniorenprüfung. Ausstellung der Berliner Sezession,” Berliner Tageblatt, October 29, 1921.

- See the chapter “The Critics and the ‘Demise’ of Expressionism,” in German Expressionism: Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National Socialism, ed. Rose-Carol Washton Long and Stephanie Barron (New York: Hall, 1993): 280–96.

- Franz Roh, “Ausstellungen. München,” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 10 (October 1921): 318.

- The Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin had been pupil of Burckhardt and Dilthey; after teaching in Basel and Berlin he came to Munich in 1912. Here he published his fundamental text about the “Principles of Art History” in 1915, and in 1916 Roh became his assistant; see Heinrich Wölfflin, Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Das Problem der Stilentwickelung in der neueren Kunst (Munich: Bruckmann, 1915).

- Franz Roh, Holländische Malerei (Jena: Eugen Diederich, 1921), 2.

- Ibid., 3.

- See Franz Roh, Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus (Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1925). On the historical context of this edition, see Emily Braun, “Franz Roh. Tra postespressionismo e realismo magico,” in Realismo magico. Pittura e scultura in Italia 1919–1925, ed. Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (Milan: Mazzotta, 1988): 57–64; and Christian Fuhrmeister, “Hartlaub and Roh: Cooperation and Competition in Popularizing New Objectivity,” in Barron and Eckmann, New Objectivity, 40–49.

- Paul Westheim, “Nach-Expressionismus,” Berliner Börsenzeitung, January 22, 1926.

- Roh, Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus, 76–77.

- Carlo Carrà, Georg Schrimpf (Rome: Valori Plastici, 1924).

- See, for instance, the classic overview of the period in Elena Pontiggia, Modernità e classicità. Il ritorno all’ordine in Europa, dal primo dopoguerra agli anni Trenta (Milan: Mondadori, 2008); or the recent exhibition catalogue Anni venti in Italia. L’età dell’incertezza, ed. Matteo Fochessati and Gianni Franzone (Genoa: Sagep Editori, 2019).

- For the circulation among Italian artists of German illustrated journals and visual sources in the prewar period, see Nicol Mocchi, “Il modello austro-tedesco per i pittori italiani negli anni del Simbolismo. Qualche ipotesi di ripresa visiva,” Prospettiva, nos. 165–66 (January–April 2017): 142–65.

- Roh, Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus, 79.

- See Angelica Müller-Scherf, “Klassizismus und Realismus im Werk von Edmund und Alexander Kanoldt,” in Alexander Kanoldt: 1831–1939. Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Lithographien, ed. Michael Koch (Waldkirch: Wladkircher Verlag-Gesellschaft, 1987): 11–27.

- Guido Lodovico Luzzatto, “Rassegna d’arte. La Nuova Secessione di Monaco. Soggetti e ispirazioni italiane in pittori tedeschi,” Rivista d’Italia 27, no. 1 (February 1924): 252.

- Roh, Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus, 54.

- See Christoph Vögele, Niklaus Stoecklin und die neue Sachlichkeit (PhD diss., Universität Zürich, 1993), 155–56.

- See Eugen Lüthgen, “Carlo Mense. München,” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration 50, no. 25 (May 1922): 58–66.

- See Catalogo della prima mostra del Novecento Italiano. Febbraio–Marzo 1926 (Milan: Gualdoni, 1926); and Seconda mostra del Novecento italiano. Catalogo. 2 marzo–30 aprile 1929 (Milan: Gualdoni, 1929).

- See Giuseppina Dal Canton, “La cultura figurativa di Cagnaccio,” in Cagnaccio di San Pietro, ed. Renato Barilli (Milan: Electa, 1991), 23–24.

- Roh, Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus, 47.

- See Fagiolo dell’Arco, Realismo Magico, 336–39.

- Internationale Kunstausstellung Dresden 1926 June–September (Dresden: Jahresschau Deutscher Arbeit, 1926), 44–45.

- Däubler, “Neueste Kunst in Italien.”

- Will Grohmann, “Die Kunst der Gegenwart auf der Internationalen Kunstausstellung Dresden 1926,” Der Cicerone 18, no. 12 (June 1926): 408.

- See Elena Pontiggia, “Lipsia 1928. Roh e il Novecento Italiano,” Storia dell’arte 13/14 (2006): 269–77.

- Franz Roh, “Bemerkungen zur nachexpressionistischen Malerei Italiens,” Die Kunst für Alle 43 (1927–28): 168–80.

- On the ideological discourse of the Novecento Italiano during the 1920s, see Rossana Bossaglia, Il Novecento Italiano. Storia, documenti, iconografia (Milan: Feltrinelli 1979); and Daniela Ferrari, Danka Giacon, Anna Maria Montaldo, and Antonello Negri, eds., Margherita Sarfatti (Milan: Electa, 2018).

- Wilhelm Worringer, “Carlo Carrà’s ‘Pinie am Meer’. Bemerkungen zu einem Bilde,” Wissen und Leben 27, no. 18 (1925): 1165–69. See also his letter to Carrà, May 12, 1924, published in Fagiolo dell’Arco, Realismo Magico, 335.

- Italo Tavolato, “Chronik der futuristischen Instauration,” Das Kunstblatt 9, no. 6 (June 1925): 354–65.

- Italo Cremona, Felice Casorati (Turin: Accame, 1942), n.p.