The Critical Fortune and Artistic Recognition of the Work of Depero

Fabio Belloni Fabio Belloni Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/

Unlike other Futurist artists, Fortunato Depero was recognized as a modern master only after his death in 1960, in his birthplace of Rovereto. This paper aims to investigate the steps of the rehabilitation and reassessment of Depero’s work that took place between 1960 and 1980, focusing on exhibition history, the contributions of critics and historians, and the works of a later generation of artists inspired by Depero.

Today, Fortunato Depero is unanimously regarded as a key figure in the artistic scene of twentieth-century Italy. Over the past decades, many studies have shed light on his strengths: his original and autonomous reading of Futurism, his sojourn in New York at a time when Paris was still the preferred destination of artists, and above all his ability to go beyond the traditional hierarchies of artistic genres, remaining open to very different techniques and spheres.1 But the importance of Depero’s art has not always been recognized. For a long time, both before and after his death, a simplistic interpretation of the artist and his work prevailed. From this viewpoint, Depero appeared as a subordinate, minor author greatly dependent on his mentor Giacomo Balla, and was pigeonholed in that series of experiments that for a long time were defined, more or less properly, as ‘Second Futurism.’2

Depero died after a lengthy illness at the age of sixty-eight in Rovereto on November 29, 1960, a year marked by the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of the first Futurist manifesto. At that point, studies about the movement began appearing frequently: the rapid succession of exhibitions and publications was unprecedented in both number and scope.3 Two years earlier in Rome, Maria Drudi Gambillo, and Teresa Fiori published the first volume of a work that is still quintessential today: Archivi del futurismo (Archives of Futurism), a text which, for the first time, lent some philological order to the jumble of writings, manifestos, and declarations produced by the Futurists.4

That initiative prefigured the large exhibition devoted to Futurism held the following year, again in Rome, at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni. By 1960, studies of Futurism had spread: the Venice Biennale, which would be remembered for having confirmed the triumph of Art Informel, included a historical show of Futurism. At the same time Milan saw both the opening of the International Institute for Studies on Futurism, an organization focusing on the promotion of knowledge about the movement by way of first-hand documents, and, between 1959 and 1960, a course on the origins of Futurism taught by Guido Ballo at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera.5 Raffaele Carrieri, meanwhile, was working on a monograph of the movement, which would be published by the Galleria Il Milione in 1961.

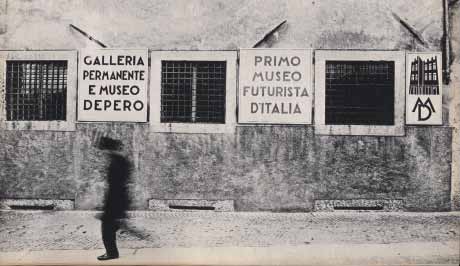

In the midst of all this, in 1959, a different but no less significant event took place: the inauguration in Rovereto of the Galleria Permanente e Museo Depero (figure 1). This opening was much talked about for at least two reasons: it was the first museum in Italy entirely devoted to a contemporary artist while he was alive, and it was – as the sign at its entrance proudly announced – “Italy’s First Futurist Museum.”

This can be fairly easily explained: for the public of the day, Depero was not an author endowed with the same dignity as was attached to other Futurists. He was not Umberto Boccioni, nor Giacomo Balla, nor Gino Severini, nor even Carlo Carrà. This explains why – with the exception of acquisitions by Gianni Mattioli – his works did not find their way into the most important private collections of the era. Depero’s canvases, tapestries, and sculptures are missing from the holdings of Milanese collectors Riccardo Jucker and Emilio Jesi, just as they are absent from the few but noteworthy international collections of Futurist works, such as those of Lydia Winston Malbin in the United States and Eric Estorick in England.

The distance between Depero and collectors of his day is worth exploring. The first and most important explanation for this situation lies in the then predominant historiographical interpretations of Futurism.7 While Depero was alive and well into the late 1960s, historians confined the movement’s chronology to very precise dates: 1909 (the year of the first manifesto) to 1916 (the year Boccioni died, and Severini and Carrà moved away from Futurism). 1916 was above all a strategic date: choosing it was a way of dissociating Futurism from the birth of Fascism in 1919, which would have compromised the reputations of more than a few of the movement’s artists.8 Depero officially joined the group in 1914 and, although it is true that in the following year, together with Balla, he wrote one of its most important manifestos, Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo (Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe), he only embarked on his more mature works toward the end of that decade. For this reason, he had generally been regarded as a second generation Futurist, an artist belonging to what in the late 1950s was being called ‘Second Futurism.’9

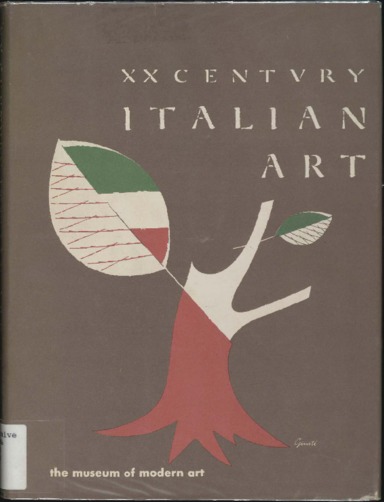

A specific exhibition was responsible for establishing Futurism’s concluding date in 1916 on an international level: the 1949 show Twentieth-century Italian Art (figure 2), curated by James Thrall Soby and Alfred H. Barr at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.10 The event was a major occasion for various reasons, not least because, for the first time, Futurism and metaphysical art were internationally recognized as the foundations of Italian modern art. The dates of the Futurist creations on view ended at 1915, which explains why Depero’s works were excluded from the installation. From archived correspondence between the artist and the curators, it is clear that Depero did try to persuade the organizers to include his work, but in the end all he could do was take note of his own exclusion.11 At the beginning of that year, Depero had returned from his second long and fruitless journey to the US, and from his writings it is evident that the curators’ choice struck him as unjust to the point of being an insult. In a letter sent to Gianni Mattioli on June 20, 1949, he vented his bitterness:

Today I received another letter from Salterini dated June 15 with, attached, Mr. Barr’s reply, in which he once and for all excludes me because my works do not belong to the period 1910–1915.12 Just as, incidentally, the following have been excluded: Prampolini, Dottori, Fillìa, and others, also because they belonged to the second Futurist wave. The letter uses these terms, not to more candidly call them Fascists!13

For Depero, the connection to Fascism was not negligible: through his paintings, projects, and advertisements, the artist had fully collaborated with the regime. And, as if that were not enough, when the state appeared to be on the brink of collapse, he had submitted for printing A passo romano (Roman Step), a volume published by the Trentino publishing house Credere, obbedire, combattere (Believe, Obey, Fight) in the spring of 1943, thus demonstrating his ignorance of the recent turn events. Depero offered an apology for his involvement with Fascism through a gloomy sequence of texts, poems, and images and, after the fall of the regime on July 25, 1943, he hurriedly destroyed the work still in his possession that could have served as compromising evidence of his recent past.14

However, it would be simplistic to interpret Depero’s misfortune in the immediate postwar years as solely a result of his collaboration with the Fascist government. Were this the only problem, it would be hard to understand why an artist politically even more exposed than he, like Mario Sironi (1885–1961), could take part in Twentieth-century Italian Art and, in the next decade, receive prizes and organize several exhibitions abroad, including in the US.15 For Depero, as for many other authors of his generation, the Fascist past was a heavy burden. Nevertheless, it was not so paralyzing as to warrant a complete disavowal since, for example, in the 1959 catalogue for his own museum – in fact, the last book that the artist edited and produced himself – he elected to publish on a double page spread, in a completely detached manner, one of his old sketches for a large mural featuring both swastikas and fasces.16

In light of the reception of other artists with ties to the regime, there must have been alternate rationale behind that estrangement. In other words, there must have been another reason why Depero had earned the attention of neither the most important critics of the day – from Giulio Carlo Argan to Cesare Brandi, and from Giuseppe Marchiori to Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti – nor the most seasoned dealers – notably Carlo Cardazzo, owner of the Venetian gallery Il Cavallino, with whom, in the 1950s, he had planned one or two ultimately unrealized solo shows.17 To answer this quandary, one must consider the tastes of the day and the predominant aesthetics shared by most people. Depero’s best-known works – in other words, those that were frequently featured in exhibitions and specialized magazines – date to the years between the 1940s and the 1950s and exhibit an odd mixture of Futurism, metaphysical art, and Surrealism; in other words, they were characterized by an unusual and not always persuasive form of painting. They were the product of an artist in decline; a creator who had lost the vitality of his early years and assumed something akin to an excessive burden, wherein a vernacular taste was combined with frequent visionary accents. “In an excessive display of his wit,” Bruno Passamani accurately assessed Depero’s practice, writing:

Depero transfers the formal proposition into the sphere of the grotesque, achieving one of the most sensational profanations to the detriment of painting itself, and of dynamic painting.18

Such an approach turned out to be incapable of establishing a relationship with its own time: the artist was unable to come up with solutions to the problems that contemporary artists and critics were discussing, such as those involving abstraction and an art with social implications. Depero appeared as an evasive painter, lost in a world of fable, as far removed as can be imagined from the issues of ‘engagement’ that were en vogue. Taken in its entirety – then as now, incidentally – Depero’s artistic output seemed to be the product of an uneven creator, one not easy to place within the narratives of Italian artistic tradition. His cheerful, ironic, playful, and often decorative character made him almost an anomaly in a twentieth-century vein. His eccentric, multidisciplinary practice – was he a painter, a graphic artist, an advertiser, or a set designer? – set him apart, rendering him far removed from that of the figure of the pure painter, still so appreciated in a culture permeated with Crocian ideas.19

In the immediate postwar years, some Futurists (in particular Balla and Severini), became important examples for the latest generation of artists embarking on the road to abstraction.20 Depero could also have been a model, but this did not happen for one simple reason: until the late 1960s, he remained a mysterious artist and a fairly obscure figure whose pictures were limited both in exhibitions and reproductions. While there was a whole museum dedicated to his work in Rovereto, to a considerable degree it was a gallery filled with late works. Therefore, it painted a biased vision of the artist’s oeuvre. In addition, the numerous books published over the decades like so many extensive repertories of his work – above all Depero futurista (also known as the ‘Bolted Book’ of 1927) and his 1940 autobiography, Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita (Fortunato Depero in His Works and Life) – remained rare editions, not really in circulation. This problem was compounded by the fact that many of his earliest works had been lost, destroyed, or else were held in inaccessible collections, like those of Léonide Massine and Sergei Diaghilev. Photographs were the ornly evidence of their existence, aside from the remakes that the artist started to produce from the late 1940s on, attempting to pass them off as originals.21

In the early 1960s, however, this situation started to change and Depero’s work began to be rehabilitated. From then on, the solo shows in public and private venues steadily increased in number, to the point where today his work is frequently on view. This new chapter begins with a whole host of occasions organized by Gianni Mattioli, who was the artist’s friend and keenest collector – the only person the artist could really rely on from the early 1920s to the end of his days.22 Mattioli was always behind those first exhibitions after the Depero’s death: at the Galleria Toninelli in Milan in 1962, at the Quadriennale in Rome in 1965, at the Villa Reale in Monza and at the Galleria Annunciata in Milan in 1966, at the Martano in Turin in 1969, and at the Square Gallery in Milan in 1971, just to name a few. Indeed, the first major Depero retrospective, held at the Museo Civico in Bassano del Grappa in summer 1970, was Mattioli’s brainchild.

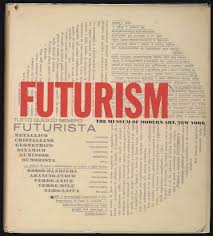

US audiences, too, were finally becoming aware of the artist from Rovereto. The great exhibition on Futurism organized by the Museum of Modern Art in 1961 (figure 3) continued to select works based on the canonical dates, and thus excluded Depero’s oeuvre, but oddly enough for the catalogue cover Joshua Taylor chose a parolibera (word-in-freedom) plate taken from Depero’s ‘Bolted Book.’ The following year, in 1962, the New York Public Library celebrated Igor Stravinsky’s eightieth birthday with an exhibition titled Stravinsky and the Dance. For the occasion, one or two photographs and sketches for Le Chant du rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale) were exhibited. Then, between 1967 and 1970, it became possible to see other important works from the Mattioli Collection in the show that toured Washington D.C., Dallas, New York, and other American cities.

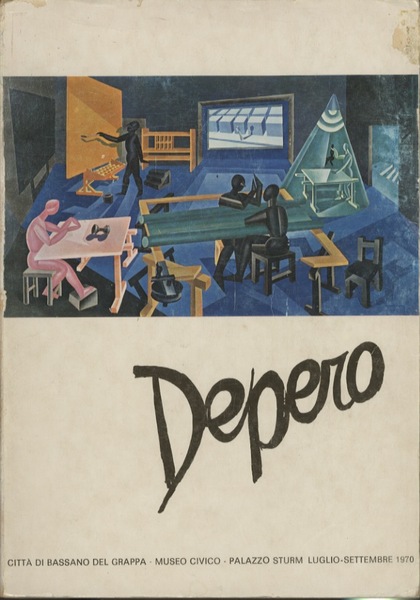

At the turn of the decade, there erupted what we could perhaps describe as the ‘Depero case.’ For the first time, thanks in large part to the gradual reorganization of his documentary archive and the parallel critical relaunching of Balla, the artist from Rovereto began to be seriously studied. It was above all thanks to Bruno Passamani, the young director of the Museo Civico in Bassano del Grappa who had graduated in Rome with Lionello Venturi, the curator of the first truly important exhibitions of Depero’s work (figure 4).

His catalogues became valuable tools, publishing hitherto unseen works, gathering writings, and organizing still uncertain dates. From that moment on, the artist’s name and works started to appear even in places associated with the liveliest discussions of the day. In April 1969, NAC, the most widespread contemporary art news bulletin, published on its cover Città meccanizzata dalle ombre (City Mechanized by Shadows), produced in 1919 (figure 5). Shortly thereafter, Marcatrè, the most important Italian Avant-garde magazine, and the one which had paid closer heed than others to Pop Art and Arte Povera, devoted an almost forty-page dossier to Depero and the theater.23

What sparked all of this attention? At that time a new wave of studies, shows, and books on Futurism was emerging. A different generation of interpreters was re-reading Futurist art without the encumbrances and preconceptions that had hitherto hampered research. A more tranquil analysis was ushered in: as already pointed out by Günter Berghaus, the equation ‘Futurism equals Fascism’ was gradually losing ground.24 And then, in a more general way, people started to understand that much of what was happening in avant-garde circles, Italian and foreign alike, had its roots in the experiments carried out at the beginning of the twentieth century. This, for example, is the thesis of a crucial book from 1966, Le due avanguardie (The Two Avant-gardes; figure 6), in which Maurizio Calvesi emphasizes the continuity between past and present, and between Futurism, neo-Dada, and Pop Art.25

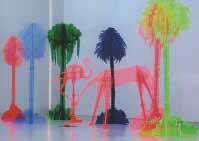

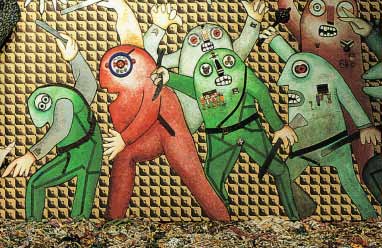

At a time when artists and critics were ever more incessantly talking about arte-gioco or game-art, Depero was becoming a figure of reference, a master; read in tune with contemporary taste, his works became surprisingly topical.27 His exotic, colorful, and unreal character returned in the methacrylate sculptures of Gino Marotta (1935–2012; figures 7–8), the multiplication of imagery re-carved in the wooden works of Mario Ceroli (b. 1938; figures 9–10), and the grotesque aspect on the canvases of Enrico Baj (1924–2003; figure 11), for example.

Experiments involving visual poetry, design, and even behavioral research all seemed to have a kindred connection even though none of these aforementioned authors and groups have ever themselves expressed personal devotion to Depero, and one should certainly not think that their works are dependent on him. It is, however, important to understand that the visual climate of that time seemed the most attuned and disposed to the artist’s rehabilitation.

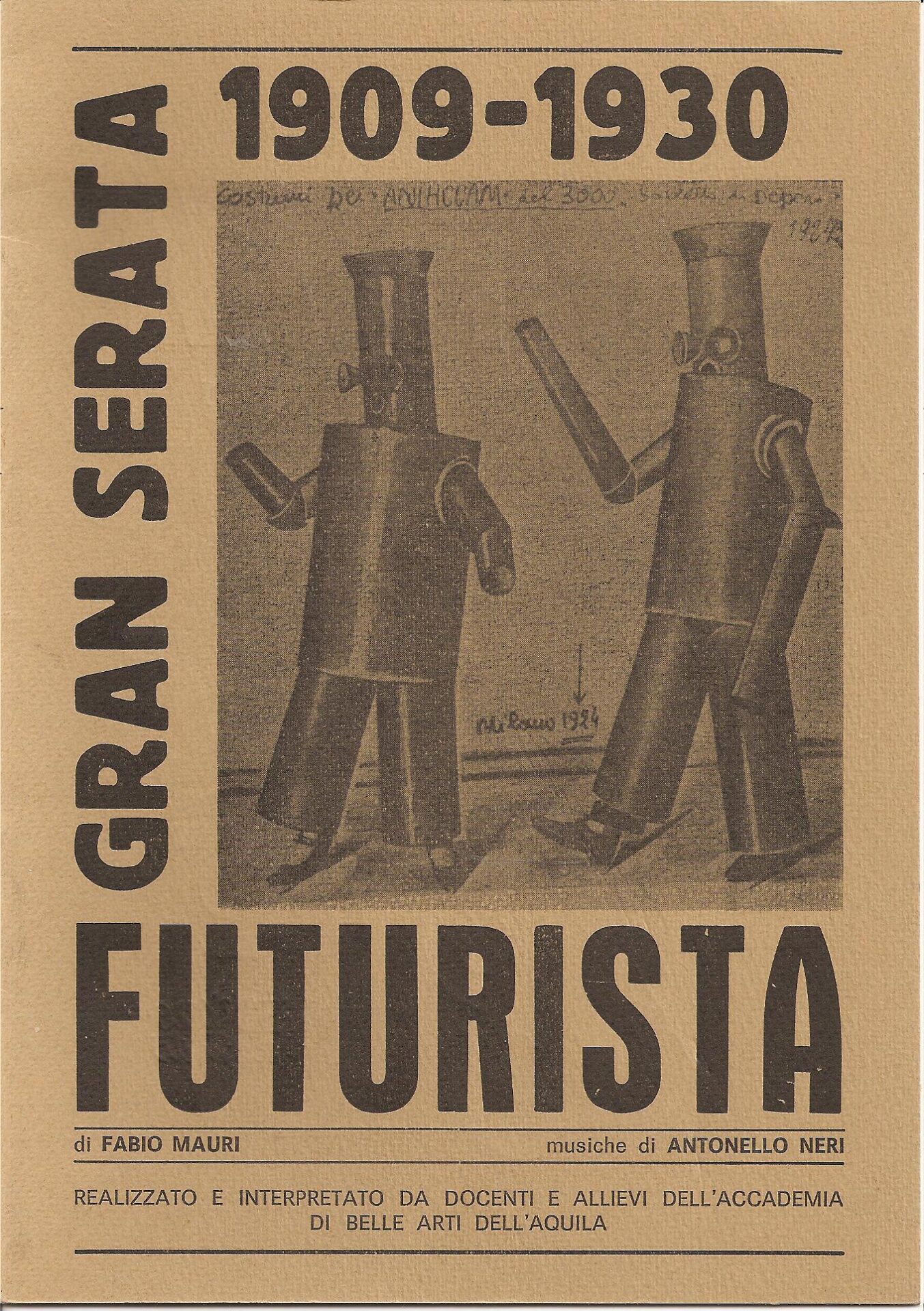

Among these projects, there is one that stands out in its tribute to Depero. In September 1980, at the Teatro Comunale in L’Aquila, Fabio Mauri (1926–2009) presented Gran Serata Futurista 1909–1930 (figure 12), a show that lasted all of four hours and was performed by more than fifty actors. With philological attention, the disruptive energy of Futurist encounters was re-created on stage: words-in-freedom (parole in libertà) were recited, music of the day was played, and films of the period were screened. For Mauri, a sophisticated artist who, for years, had focused his own work on the theme of personal and collective memory, above all this amounted to a fitting tribute to Depero.

Many reproductions of his pictures were shown in succession, and the sets for Le Chant du rossignol and the costumes for Anihccam del 3000 (figures 13–14) were also reproduced.28 It was no coincidence that this all came about at the end of 1980. Shortly beforehand, the Florentine publishing house Spes had reprinted the exceedingly rare ‘Bolted Book,’ while Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo, the great exhibition devoted to Futurism curated by Enrico Crispolti in Turin in spring 1980, had ushered in Depero’s definitive rehabilitation.29

Bibliography

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949.” Oxford Art Journal 35, 2 (December 2012): 147–169.

Belloni, Fabio. “The Critical Fortune and Artistic Recognition of the Work of Depero.” In Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, edited by Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, 347–353. Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Benzi, Fabio. Il Futurismo. Milan: Motta, 2008.

Berghaus, Günter. Futurism and Politics: Between Anarchist Rebellion and Fascist Reaction, 1909–1944. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1996.

Berghaus, Günter. “The Postwar Reception of Futurism: Repression or Recuperation?” In The History of Futurism: The Precursors, Protagonists, and Legacies, edited by Geert Buelens, Harald Hendrix, and Monica Jansen, 377–403. New York: Lexington Books, 2012.

Borgese, Leonardo. “Si è spento Fortunato Depero il più metodico pittore del futurismo.” Corriere della Sera (November 30, 1960).

Braun, Emily. Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Barbero, Luca Massimo, ed. Carlo Cardazzo: una nuova visione dell’arte. Milan: Electa, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Barilli, Renato, ed. Nuovo futurismo: Abate, Innocente, Lodola, Plumcake. Postal. San Marino: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna; Rovereto: Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto; Milan: Electa, 1994. Exhibition catalogue.

Calvesi, Maurizio. Le due avanguardie: Dal futurismo alla pop art. Milan: Lerici, 1966.

Catalogo della Galleria e Museo Depero, Rovereto: Il primo museo futurista d’Italia. Rovereto: Temi, 1959.

Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn and Marcella Cossu. Fabio Mauri: Opere e azioni, 1954–1994. Milan: Mondadori; Rome: Carte Segrete, 1994.

Cioli, Monica. Il fascismo e la sua arte. Florence: Olschki, 2011.

Crispolti, Enrico. Appunti sul problema del secondo futurismo nella cultura italiana fra le due guerre. Turin: Edizioni della Galleria Notizie, 1958.

Crispolti, Enrico. “The Dynamics of Futurism’s Historiography.” In Italian Futurism 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, edited by Vivien Greene, 50–57. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Depero, Fortunato. A passo romano: lirismo fascista e guerriero programmatico e costruttivo. Trento: Edizioni Credere Obbedire Combattere, 1943.

Drudi Gambillo, Maria and Teresa Fiori. Archivi del futurismo. Rome: De Luca, 1958–1962.

Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Maurizio. Futur-Balla. Rome: Bulzoni, 1970.

Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Maurizio, ed. Depero. Milan: Electa, 1989. Exhibition catalogue.

Garin, Eugenio. Cronache di filosofia italiana 1900–1943: In Appendice Quindici anni dopo 1945–1960. Bari: Laterza, 1975.

Gentile, Emilio. La nostra sfida alle stelle: Futuristi in politica. Rome: Laterza, 2009.

Kirby, Michael. Futurist Performance. New York: Dutton, 1971.

Lista, Giovanni. “L’eredità del futurismo.” In Futurismo, 1909–2009: Velocità+Arte+Azione, edited by Giovanni Lista and Ada Masoero, 272–291. Milan: Skira, 2009.

Lista, Giovanni. “L’esperienza futurista di Fortunato Depero.” In Fortunato Depero: Ricostruire e meccanizzare l’universo, edited by Giovanni Lista, 217–219. Milan: Abscondita, 2012.

Mattioli Rossi, Laura. “The Collection of Gianni Mattioli from 1943 to 1953.” In The Mattioli Collection: Masterpieces of the Italian Avant-garde, edited by Flavio Fergonzi, 13–61. Milan: Skira; London: Thames and Hudson, 2003.

Montana, Guido. Socialità del gioco e valore estetico. Genoa: Silva, 1966.

Passamani, Bruno. Fortunato Depero. Rovereto: Musei Civici – Galleria Museo Depero, 1981. Exhibition catalogue.

Poli, Francesco and Stefano Della Casa, eds. Nespolo, ritorno a casa: Un percorso antologico. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editore, 2009. Exhibition catalogue.

Restany, Pierre. “Venezia 33 Biennale. L’homo ludens contro l’homo faber.” Domus 44, August 1966. Milan.

Rischbieter, Henning. Art and the Stage in the 20th Century: Painters and Sculptors Work for the Theater. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1968.

Salaris, Claudia. Alla festa della rivoluzione. Artisti e libertari con D’Annunzio a Fiume. Bologna: il Mulino, 2002.

Scudiero, Maurizio. “La ricerca deperiana: problemi di metodo.” In Depero, edited by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, 226–236. Milan: Electa, 1989. Exhibition catalogue.

Silva, Umberto. Ideologia e arte del fascismo. Milan: Mazzotta, 1974.

Sinisi, Silvana. “Depero: una vocazione allo spettacolo.” Marcatrè 50–55 (February–July 1969): 342–380.

How to cite

Fabio Belloni, “The Critical Fortune and Artistic Recognition of the Work of Depero,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/the-critical-fortune-and-artistic-recognition-of-the-work-of-depero/, accessed [insert date].

- This study is the outcome of a fellowship at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York. Parts of it were presented at the Fortunato Depero Study Day, CIMA, on February 21, 2014. My thanks to Laura Mattioli for having allowed me to examine the exchange of letters between Gianni Mattioli and Depero hitherto unavailable for study. For a previous version of this article see Fabio Belloni, “The Critical Fortune and Artistic Recognition of the Work of Depero,” in Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, eds. Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, exh. cat. (Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014), 347–353.

- “Depero’s misfortune can be accounted for. He was not included in the Futurist movement because his signature does not appear on the first Manifesto. He was not studied in the ‘Second Futurist’ group because his membership predated it. In reality, Depero was an integral part of the movement…. Naturally, he was actively involved up to a certain date: what is more, real Futurism spanned barely ten years (1909–1919), and Marinetti was right in saying that its momentum might last five or ten years and its heirs would be free to throw it away. Then Depero was, for years, the worst administrator of his own talent and for almost everyone ‘Depero’ is now synonymous with cushion.” Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, Futur-Balla (Rome: Bulzoni, 1970), XXII. On Depero’s discussed participation in the so-called ‘Second Futurism,’ see Giovanni Lista, “L’esperienza futurista di Fortunato Depero,” in Fortunato Depero: Ricostruire e meccanizzare l’universo, ed. Giovanni Lista (Milan: Abscondita, 2012), 217–219.

- Günter Berghaus, “The Postwar Reception of Futurism: Repression or Recuperation?” in The History of Futurism: The Precursors, Protagonists, and Legacies, eds. Geert Buelens, Harald Hendrix, and Monica Jansen (New York: Lexington Books, 2012), 377–403; Enrico Crispolti, “The Dynamics of Futurism’s Historiography,” in Italian Futurism 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, ed. Vivien Greene (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2014), 50–57.

- Maria Drudi Gambillo and Teresa Fiori, Archivi del futurismo (Rome: De Luca, 1958–1962).

- The Istituto Internazionale di Studi sul Futurismo was founded in 1960 by the Futurists Giovanni Acquaviva, Cesare Andreoni, Carlo Belloli, Alessandro Bruschetti, Tullio Crali, Nikolay Diulgheroff, Pino Masnata, Armando Mazza, and Bruno Munari. Thanks to the contribution of the Futurist poet Carlo Belloli (1922–2003), the ISISUF has an important archive and collection of Futurist art works.

- Leonardo Borgese, “Si è spento Fortunato Depero il più metodico pittore del futurismo,” Corriere della Sera (November 30, 1960): 19.

- See Fabio Benzi, Il Futurismo (Milan: Motta, 2008), 6–11.

- The literature on this subject is plentiful. See at least Günter Berghaus, Futurism and Politics: Between Anarchist Rebellion and Fascist Reaction, 1909–1944 (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1996); and Emilio Gentile, La nostra sfida alle stelle: Futuristi in politica (Rome: Laterza, 2009).

- Enrico Crispolti, Appunti sul problema del secondo futurismo nella cultura italiana fra le due guerre (Turin: Edizioni della Galleria Notizie, 1958).

- For a retrospective reading of the exhibition, see Raffaele Bedarida, “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949,” Oxford Art Journal 35, 2 (December 2012): 147–169. Also, the special edition of the review Cahiers d’Art (January 1950) devoted to Un demi-siècle d’art italien played an important part in establishing the chronology of Futurism.

- The correspondence between James Thrall Soby and Alfred H. Barr can be found today in the Fondo Fortunato Depero, “Mostra d’arte di avanguardia italiana a New York, 1949” (Dep. 3. 1. 42), in the Archivio del ‘900 of MART – Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto.

- John Salterini, an Italian-American industrialist friend of Depero since the 1920s.

- “Oggi ricevo altra lettera da Salterini – in data 15 giugno con allegata la risposta di Mr. Barr, con la quale mi si esclude tassativamente perché le opere non appartengono al periodo 1910–1915. Come pure furono esclusi di proposito: Prampolini, Dottori, Fillia ed altri anche perché appartenenti alla seconda ondata futurista. La lettera parla in questi termini, per non voler dire più francamente fascisti!”

- Umberto Silva’s Ideologia e arte del fascismo (Milan: Mazzotta, 1974), the first Italian book devoted to the art of the period, published some illustrations from Fortunato Depero, A passo romano: lirismo fascista e guerriero programmatico e costruttivo (Trento: Edizioni Credere Obbedire Combattere, 1943), pointing to them as a pure example of Fascist art.

- Emily Braun, Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). For details, see the chapter “Sironi in Context,” 1–17.

- Catalogo della Galleria e Museo Depero, Rovereto, il primo museo futurista d’Italia (Rovereto: Temi, 1959), 70–71. In general, for the relations between art and politics at that time, see Monica Cioli, Il fascismo e la sua arte (Florence: Olschki, 2011).

- This information was gleaned from a postwar correspondence between Carlo Cardazzo and Depero accessed in the Mattioli Archive. See also Luca Massimo Barbero, ed., Carlo Cardazzo: una nuova visione dell’arte, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 2008).

- Bruno Passamani, Fortunato Depero, exh. cat. (Rovereto: Musei Civici – Galleria Museo Depero, 1981), 243.

- For a cultural context of the time, see Eugenio Garin, Cronache di filosofia italiana 1900–1943: In Appendice Quindici anni dopo 1945–1960 (Bari: Laterza, 1975), 489–617.

- Giovanni Lista, “L’eredità del futurismo,” in Futurismo, 1in909–2009: Velocità+Arte+Azione, eds. Giovanni Lista and Ada Masoero (Milan: Skira, 2009), 272–291.

- See Maurizio Scudiero, “La ricerca deperiana: Problemi di metodo,” in Depero, ed. Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, exh. cat. (Rovereto: Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto; Dusseldorf: Städtische Kunsthalle; Milan: Palazzo Reale, 1989), 226–236.

- Laura Mattioli Rossi, “The Collection of Gianni Mattioli from 1943 to 1953,” in The Mattioli Collection: Masterpieces of the Italian Avant-garde, ed. Flavio Fergonzi (Milan: Skira; London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 13–61.

- Silvana Sinisi, “Depero: una vocazione allo spettacolo,” Marcatrè 50–55 (February–July 1969): 342–380.

- Berghaus, “The Postwar Reception of Futurism,” 394. An explicit parallel between the Futurist experiments and the social mobilization experiments of the late 1960s is to be found in Claudia Salaris, Alla festa della rivoluzione. Artisti e libertari con D’Annunzio a Fiume (Bologna: il Mulino, 2002).

- Maurizio Calvesi, Le due avanguardie: Dal futurismo alla pop art (Milan: Lerici, 1966).

- See Michael Kirby, Futurist Performance (New York: Dutton, 1971), 73. Again in the United States, Depero’s theater work was also treated in Henning Rischbieter, Art and the Stage in the 20th Century: Painters and Sculptors Work for the Theater (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1968).

- In 1966, Guido Montana, critic and editor of the review Arte Oggi, published the essay Socialità del gioco e valore estetico (Genoa: Silva, 1966). “Arte gioco,” on the other hand, was the monographic issue published that same year by the Almanacco Letterario Bompani. While the thirty-third Venice Biennale was defined by Restany as “the Biennale of joie de vivre and game-art, of homo ludens as opposed to homo faber.” Pierre Restany, “Venezia 33 Biennale. L’homo ludens contro l’homo faber,” Domus 44 (August 1966).

- On this artist, the book of reference is still Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Marcella Cossu, eds., Fabio Mauri: Opere e azioni, 1954–1994, exh. cat. (Milan: Mondadori; Rome: Carte Segrete, 1994). Mauri paid a first indirect tribute to Depero as early as 1968 with the series of plastic sculpture installations titled Pile e cinema a luce solida (Stacks and Films in Solid Light).

- In the early 1980s, Depero’s visual fortunes found further important testimony, especially in the work of Ugo Nespolo and in that of the artists belonging to the group called Nuovo Futurismo in 1983. See Francesco Poli and Stefano Della Casa, eds., Nespolo, ritorno a casa: Un percorso antologico, exh. cat. (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editore, 2009); and Renato Barilli, ed., Nuovo futurismo: Abate, Innocente, Lodola, Plumcake. Postal, exh. cat. (San Marino: Galleria Nazionalde d’Arte Moderna; Rovereto: Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto; Milan: Electa, 1994).