Fortunato Depero in 1919

Flavio Fergonzi Flavio Fergonzi Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/

This paper juxtaposes the work of Mario Sironi and Fortunato Depero, investigating the contribution that Depero made to Italian painting during a critical time period (the year 1919 that followed the end of World War I), and discussing some of his visual references to the artistic tradition.

This short paper investigates Fortunato Depero’s contribution to Italian modernist painting in 1919, the crucial year after the end of World War I when Italian avant-garde artists recognized a need to confront international modern art, as well as the Italian historical tradition, anew. The first part compares the coeval drawings and paintings of Depero and Mario Sironi, an artist whose pictorial language – characterized by dramatic light contrasts, incumbent volumes, and an altogether tragic atmosphere – at first glance seems diametrically opposed to that of Depero. The second part discusses some traditional art historical sources that inspired Depero’s artistic production in 1919. The third and final part explains Depero’s reaction to the reproductions of one French Cubist picture and one metaphysical painting printed in the Italian art journal Valori Plastici.

I.

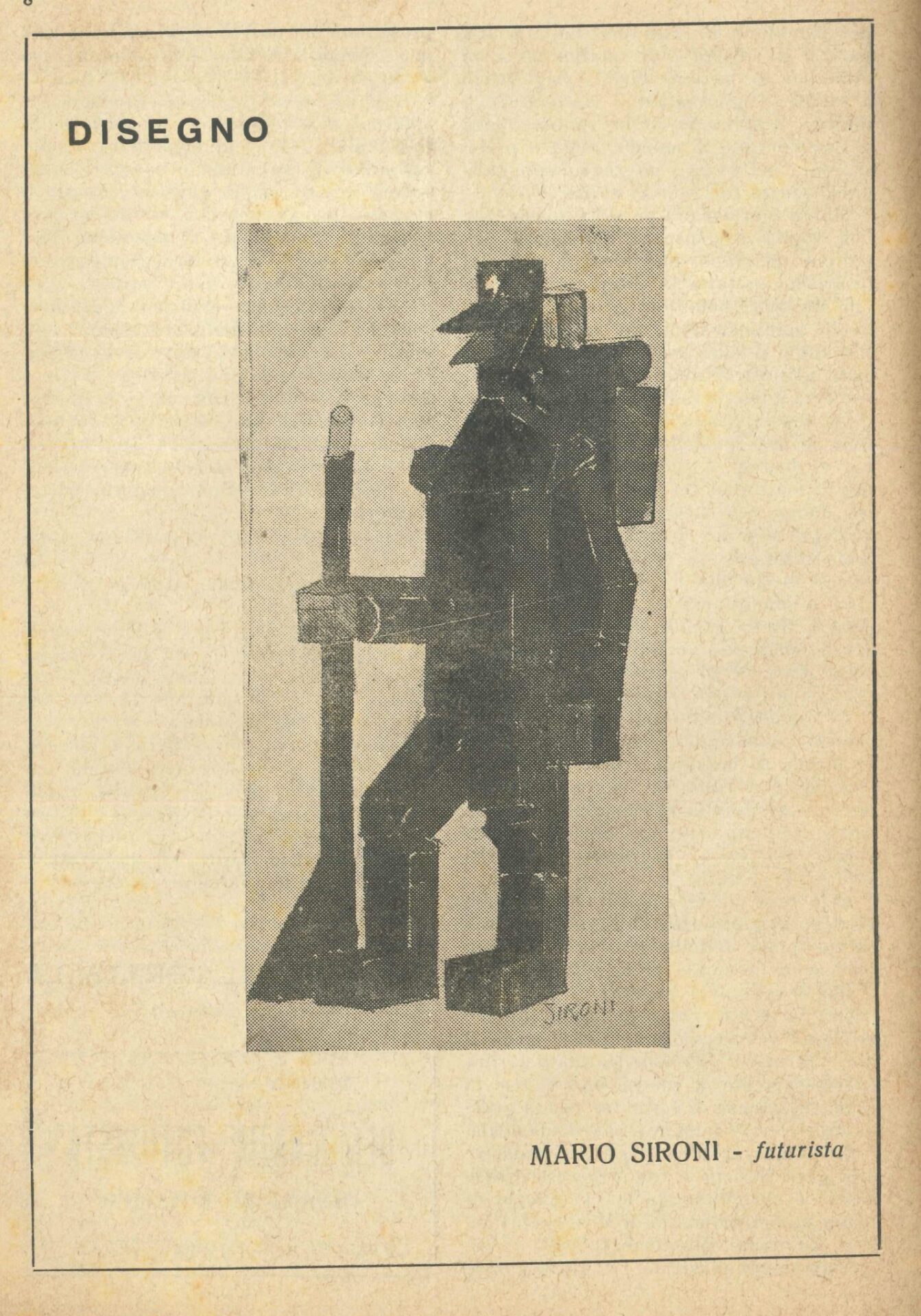

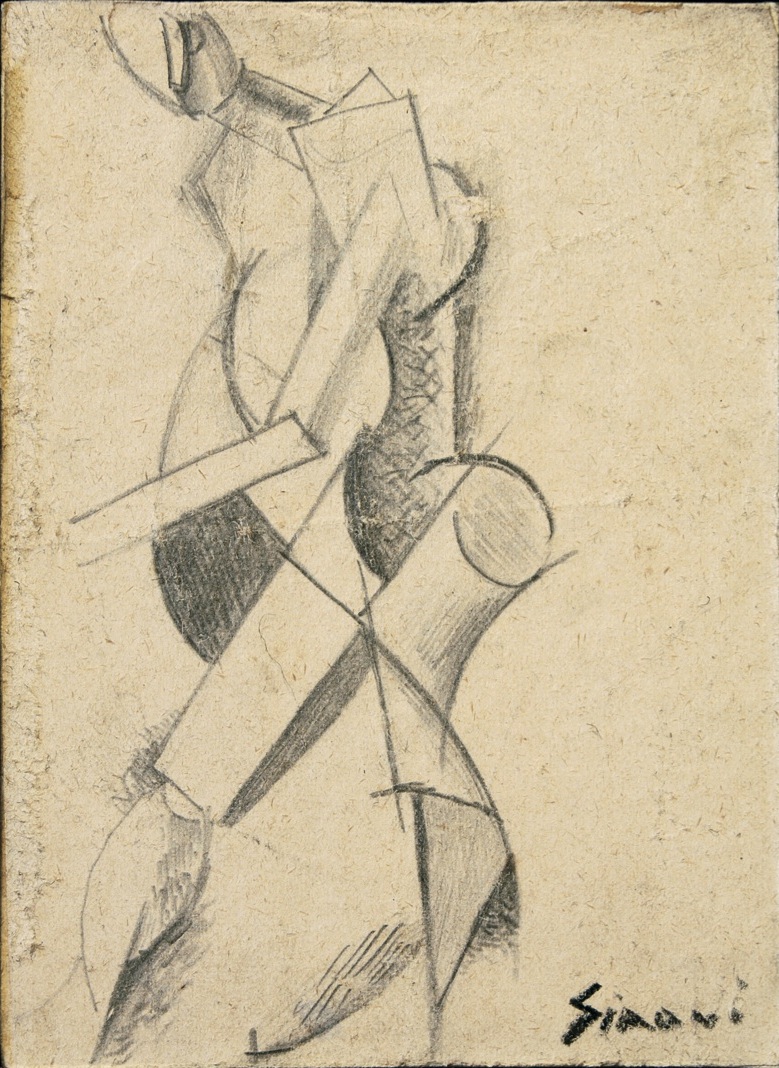

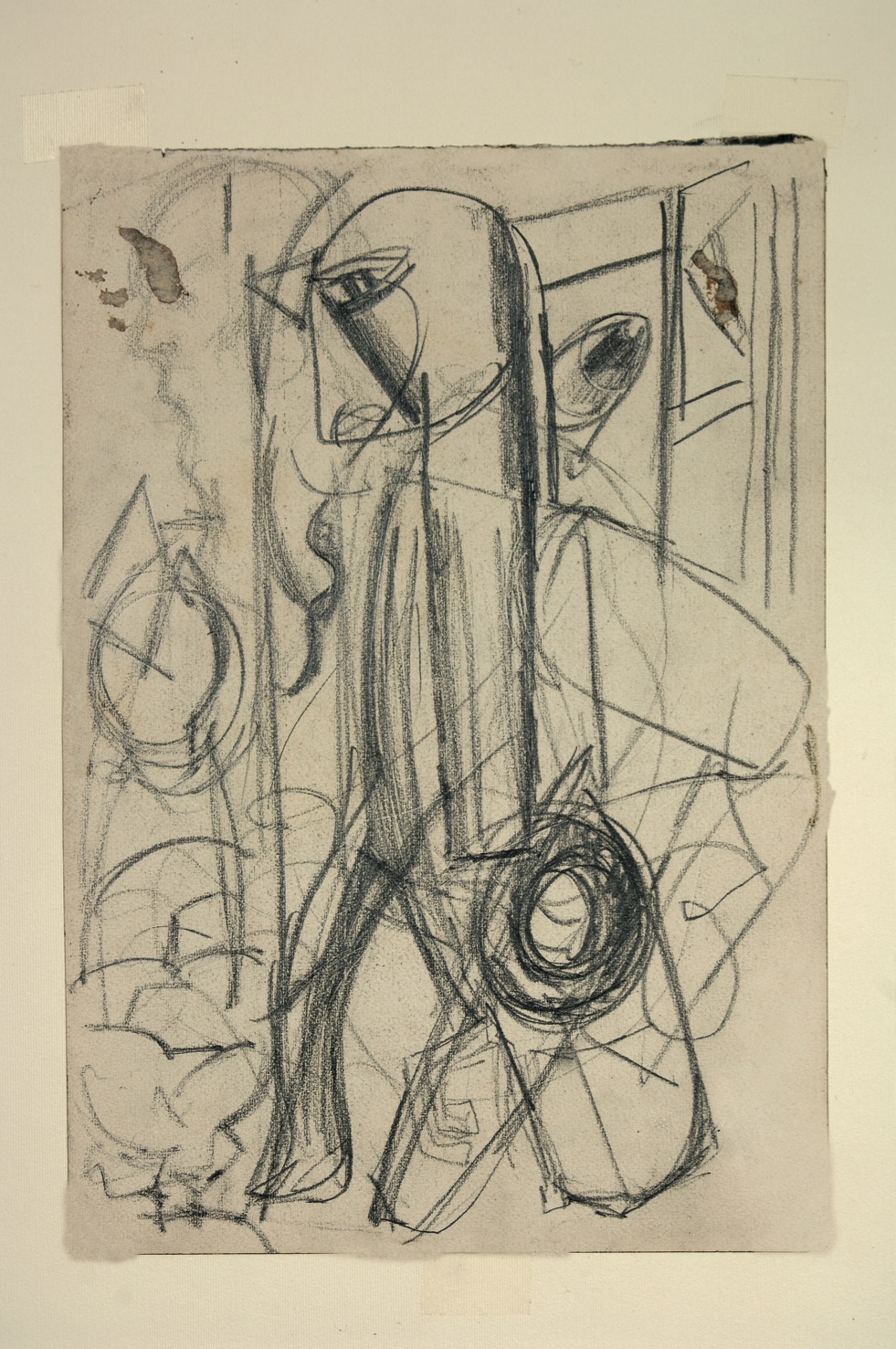

During the first half of 1919, Sironi’s style surprisingly changed. He rejected Umberto Boccioni’s ‘plastic dynamism’ (a long-time stylistic inspiration for Sironi) in favor of a pictorial language defined by the use of clear volumes, mechanical and metallic figures, and precise contours. At the beginning of 1919, Fortunato Depero was the undisputed leader of this ‘metallic’ style, and a brief glimpse at some of Sironi’s drawings from this time reveals the extent to which the artist scrutinized the visual innovations of his younger Futurist colleague. The following five comparisons demonstrate the artists’ unexpected convergence around this time.

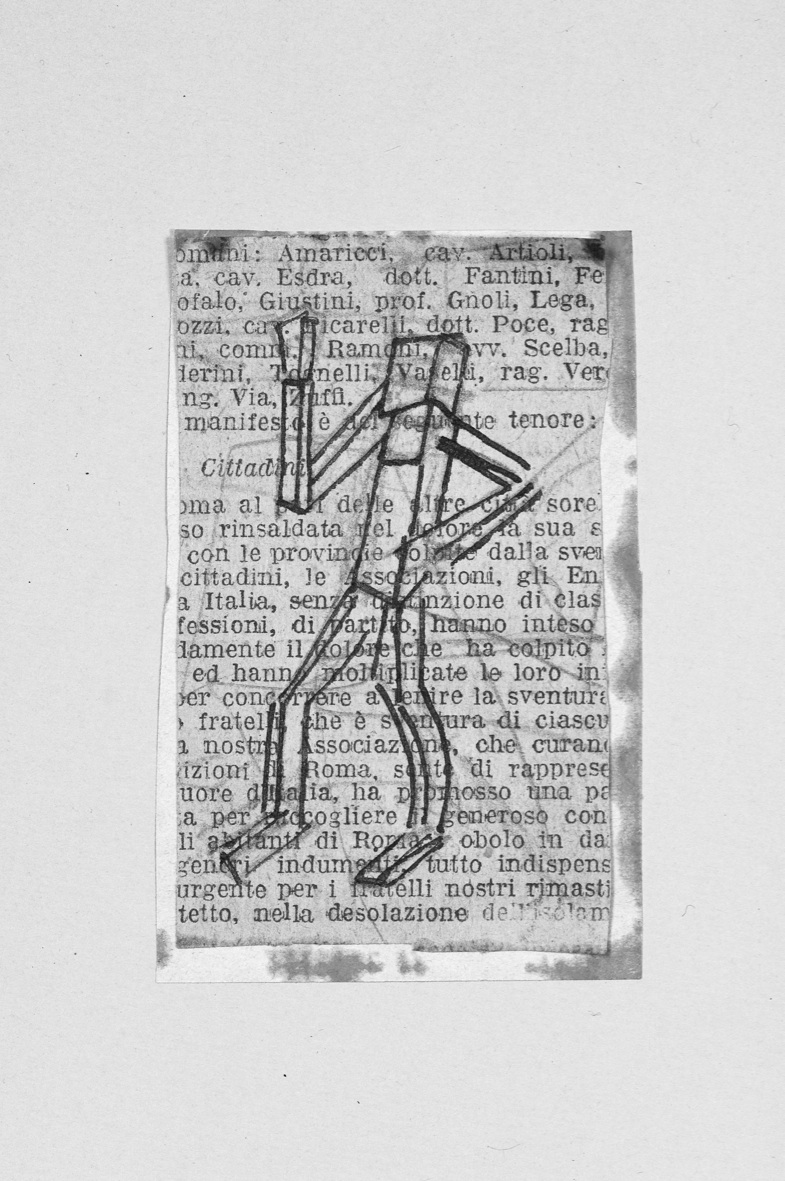

The third formal affinity between Depero and Sironi is the manner in which they reduced the body to an inanimate, inoffensive outline of a puppet or marionette that starkly contrasts with the metaphysical mannequin and its drama. The two likewise represented human figures as rigid, wooden sculptures (figures 6–7).

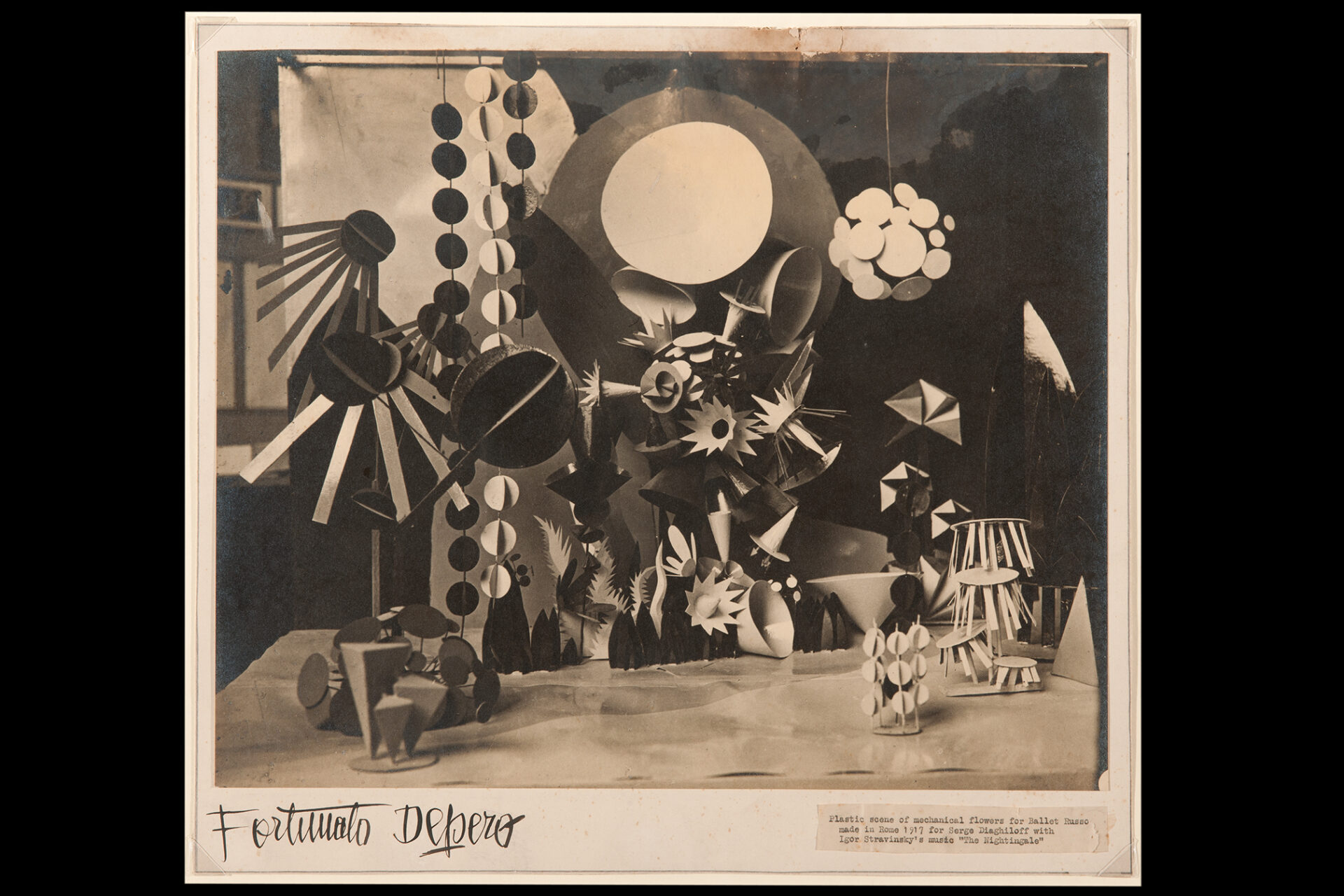

Lastly, both artists transformed subjects from the natural world (i.e. flowers and plants) into the rigid plastic forms reminiscent of stage décor (figures 8–9).

The practice of reducing of the body to a mechanic assemblage of flat and rigid outlines – the same one finds in some small, private drawings by Sironi (figure 10) – was not strictly inherited from Depero; its origin was rather polygenetic. The Futurist tradition of representing the human body as a puppet was pioneered in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s provocative Autoritratto (Self-Portrait; figure 11), which sparked heated debate in 1914, when it was displayed at the Futurist exhibition in London; however, this motif is also rooted in the works of the old masters, which, by the early twentieth century, were widely proliferated through art publications.2

For example, in 1913 a drawing by the sixteenth-century painter Luca Cambiaso, in which human figures were reduced to geometric solids (figure 12), was reproduced in Vita d’Arte, a popular monthly Italian art magazine: this composition was, in turn, closely scrutinized and ultimately disapproved of by critics hostile to Futurism as a historical precursor to Futurist inventions.3

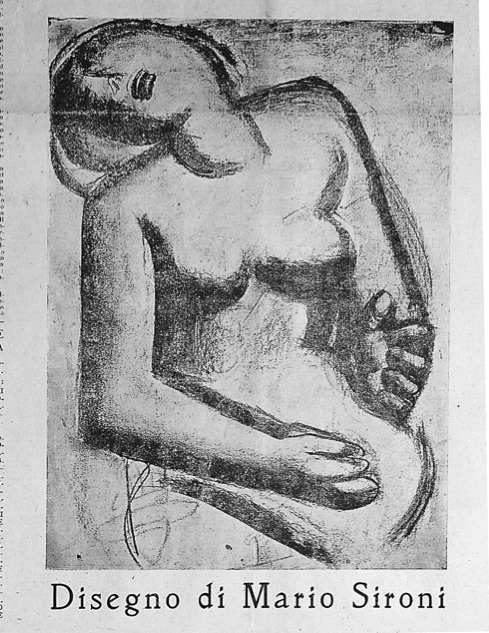

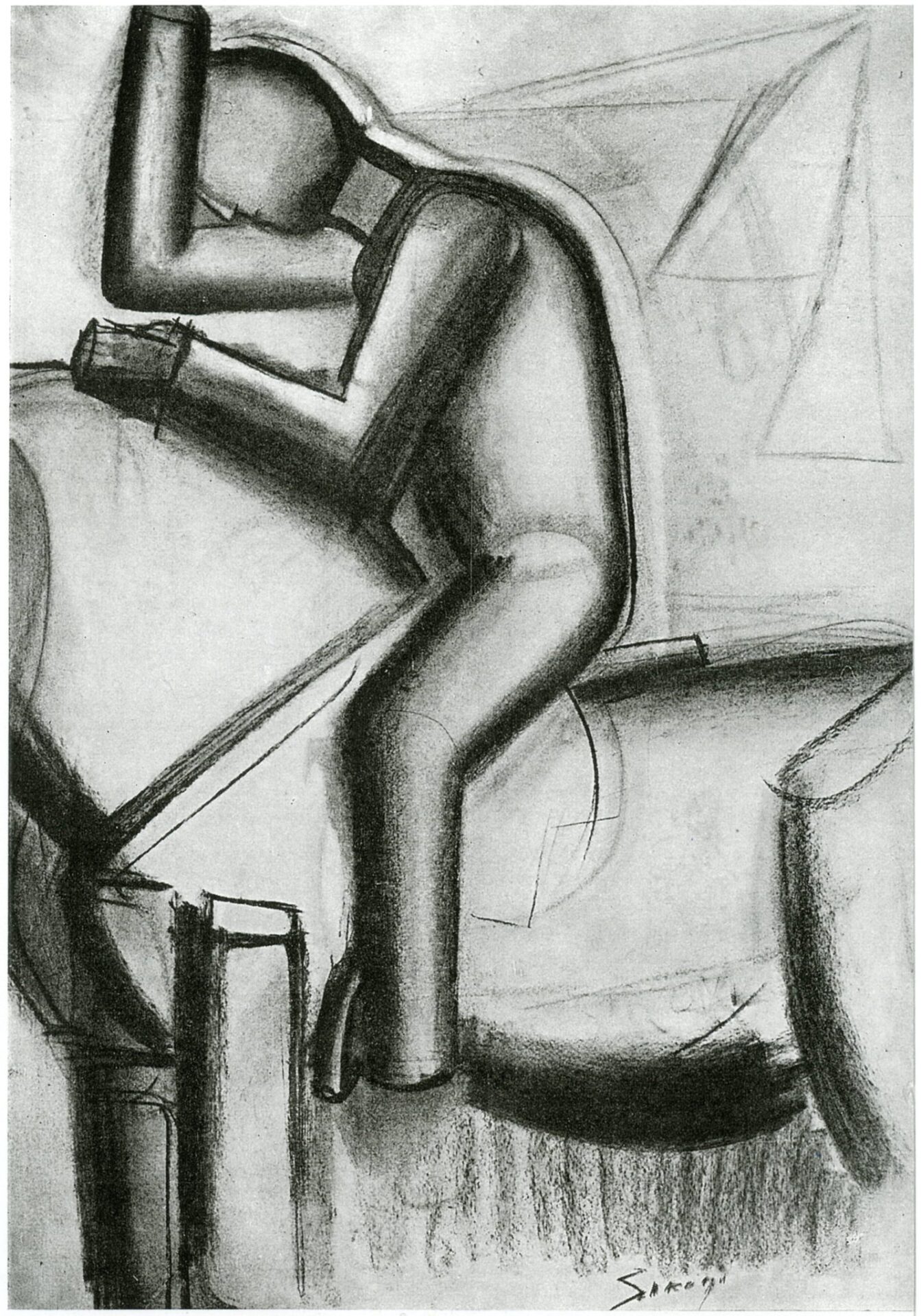

In 1919, the flat, mechanical language of Depero acted as a clear and accessible resource for many artists. In fact, his manner guided Sironi as he finished some of his tormented paintings. For instance, Sironi’s Atelier delle meraviglie (Atelier of Wonders; 1918–1919) – a confused, metaphysical composition of mannequins – was incoherently plunged into a crowded, para-Cubist setting: the mechanical design of the upper right part of the Atelier is undoubtedly inspired by some of Depero’s drawings, such as the I fumatori di ferro (Iron Smokers) – which was reproduced in Il Mondo, in April 1919.4 Sironi most likely read this Milanese periodical carefully, for the publication had printed some of his own paintings during the post-war period. If one scrutinizes the drawings exhibited by Sironi in July 1919 at his solo show at the Bragaglia Gallery, one sees that the largest and most ambitious sheets5 – like the female Figura (Figure; figure 13) in desperation and the static, monumental Uomo a cavallo (Horseman; figure 14) – are clearly indebted to the solid, rounded, polished forms of Depero’s drawings, where plastic drama appears to have been frozen by ironic mechanization. Such a connection warrants closer investigation into the context within which both artists were working.

II.

World War I ended in Italy on November 4, 1918, and all the soldiers and officers born between 1880 and 1890 were accordingly discharged from military service between February and March 1919. Most of the enlisted Futurists were included in this group, and their primary objective upon exiting the war was updating their work to match the innovations that their colleagues – in Italy and throughout Europe – had made over the past four years. Although these artists exchanged letters throughout the war and were offered access to reproductions of contemporary artworks disseminated in periodicals, these means of communication had not provided them with a comprehensive idea of what happened in modern painting in their absence.

The catalogue of the first Great National Exhibition of Futurists Painters6 that opened in Milan in March 1919 conveys the three main artistic languages adopted and elaborated on by Italian avant-garde artists during the war. The first is the pure linear dynamism of Giacomo Balla, wherein bodies and objects are reduced to abstract shapes arranged in decorative patterns that, in some cases, allude to subjects of war. The second style is diametrically opposed to the first. Adopted by a broad spectrum of painters – mainly from Tuscany and Milan – this manner was inspired by the war paintings of Ardengo Soffici and Gino Severini. It essentially translates Boccioni’s plastic dynamism into a new array of pure ‘plastic values’ and often appears to mingle with a primitivist naiveté. The third manner involves the explicit mechanization of the visual world: a body-machine usually stands in an empty pictorial space, acting as an isolated idol that does not attempt, in any way, to penetrate the surrounding atmosphere. This style manifested as the emerging modernist aesthetic in Italy after the war.

At the beginning of 1919, Depero and Balla were the leading pioneers of the Futurist movement. The former’s exhibition at the Bragaglia Gallery in February was a triumph in the field of media coverage: the art on display was not only discussed by critics, but largely reproduced in the print.7 The show was also significant because Depero had gone beyond the limits of traditional painting to produce works of stage design and interior decoration.

When evaluating the reception of Depero’s output at this time, it is particularly intriguing to consider the responses of Roberto Longhi and Margherita Sarfatti, who, by 1919, were two of Italy’s leading art critics. Although both of these writers had, only few years earlier, appreciated Boccioni’s prevailing aesthetic of ‘plastic dynamism,’ they aggressively attacked the post-war art of Depero. Longhi ridiculed “the men-coffee pot, the men-harrow” as an imitation of de Chirico’s style, asserting that the long-awaited “synthesis of form and color” was totally absent in the cold arabesque of Depero’s flat surfaces.8 Sarfatti, in a very detailed review of the Great Futurist Exhibition in Milan, connected Depero to Leon Bakst and Mikhail Larionov, highlighting the ‘Asian’ sources of the painter. In making these comparisons, Sarfatti implied that the artist was hindered by the same limitations of a ‘scenografic painter’ and, thus, lacked a constructive sense of color. In her opinion, even Depero’s best works amounted to little more than meager black and white drawings.9

Depero’s stylistic choices were also problematic among the inner circle of orthodox Futurists. Even Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the leader of the Futurist Movement, expressed his perplexities about the painter. On December 28, 1918, for instance, he published the following in Taccuini:

I have dinner with Depero at the Gambrinus Restaurant [in Naples]. He is hyper-excited and volcanic. But he has not a clear view on art. He loves and exalts Vittore Carpaccio. He asserts that Carpaccio did Futurist things, as he painted polyphonic music in his variations of rhythmic draperies. He [Depero] considers a manifestation of Futurist genius his own return to forms which are classical, cold and stylized. His wonderful impulse for impressionism, dynamism and intensity has been abandoned. He loves synthesis, but he is lost among archaism and an ancient Egyptian frigid style. So he is trying to legitimate his choice with exaltation of Carpaccio as Futurist. He does not understand Balla’s latest paintings.10

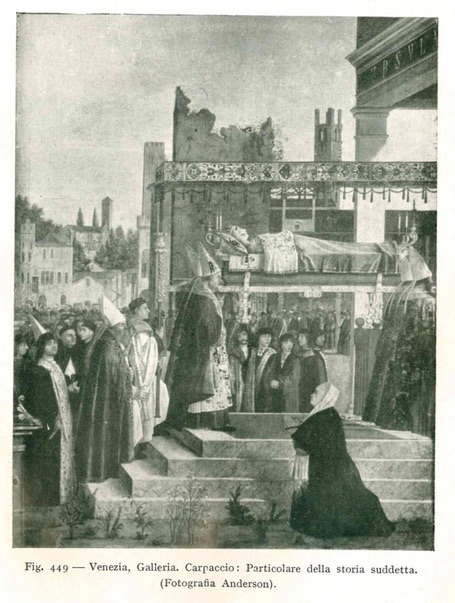

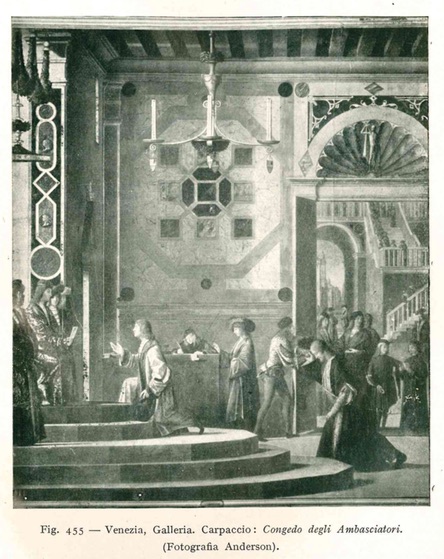

Let us consider two reproductions (figures 15–16) of details from the teleri (large-scale painting cycles) of the History of Sant’Orsola in Venice (from Il martirio dei pellegrini e i funerali di Sant’Orsola, 1493; and Il congedo degli ambasciatori, c. 1495; The Martyrdom of the Pilgrims and the Funeral of St Ursula and The Ambassadors Depart), conceived by Vittore Carpaccio, the Renaissance master referenced in the above passage by Marinetti: these black and white Anderson photographic prints were both published in the fourth volume of La pittura del Quattrocento,11 the seventh part of the monumental Storia dell’Arte Italiana, written by the eminent art historian Adolfo Venturi. Despite its passéiste historical erudition and old-fashioned prose, this text was carefully read by some of the Futurist artists. The fascinating black and white details of works by old masters dispersed throughout each volume motivated young artists to look, in a more modern way, at masterpieces of the past. As Federica Rovati has demonstrated, Carlo Carrà discovered decisive inspiration for his essay on the modernity of Giotto (1916) in Venturi’s Pittura del Trecento.12 This text encompassed details of Giottesque frescoes that ultimately influenced the characteristics of Carrà’s body of work from 1916, which features the dramatic isolation of forms from the surrounding painting field. In a similar vein, the reproductions of Carpaccio’s teleri in Venturi’s Il Quattrocento spurred Depero to set and balance his figures, with theatrical (and slightly mechanical) gestures suspended in time, as if they were acting on a sort of unrealistic stage.

III.

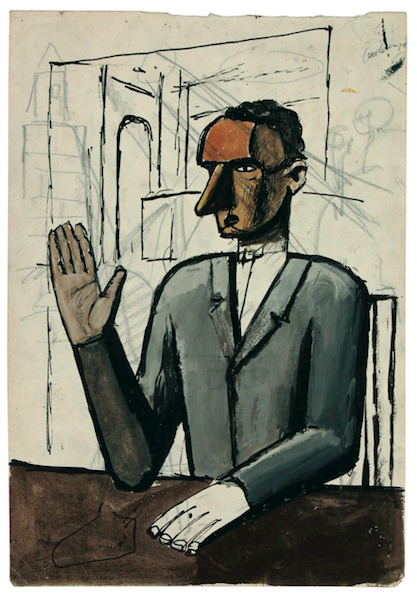

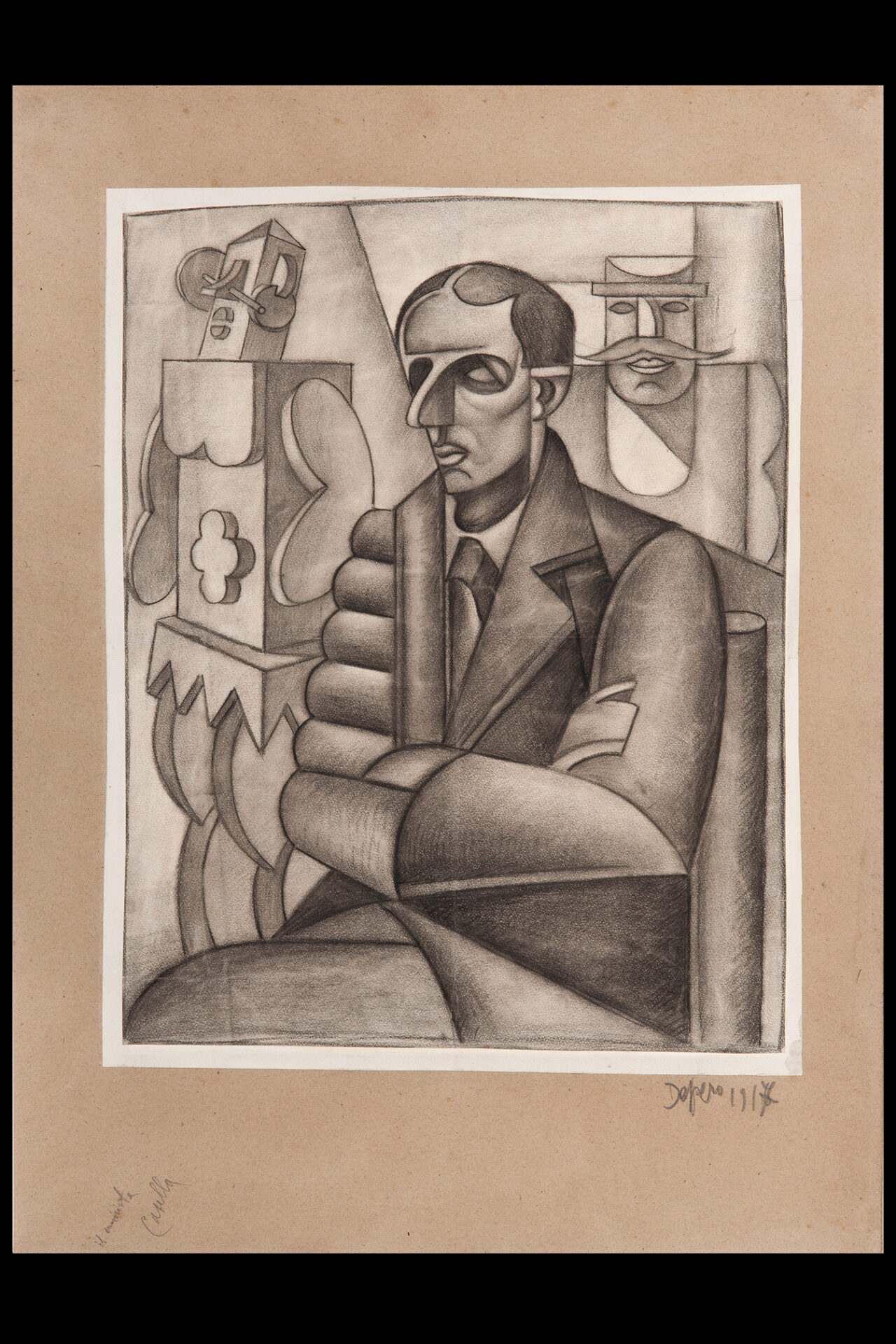

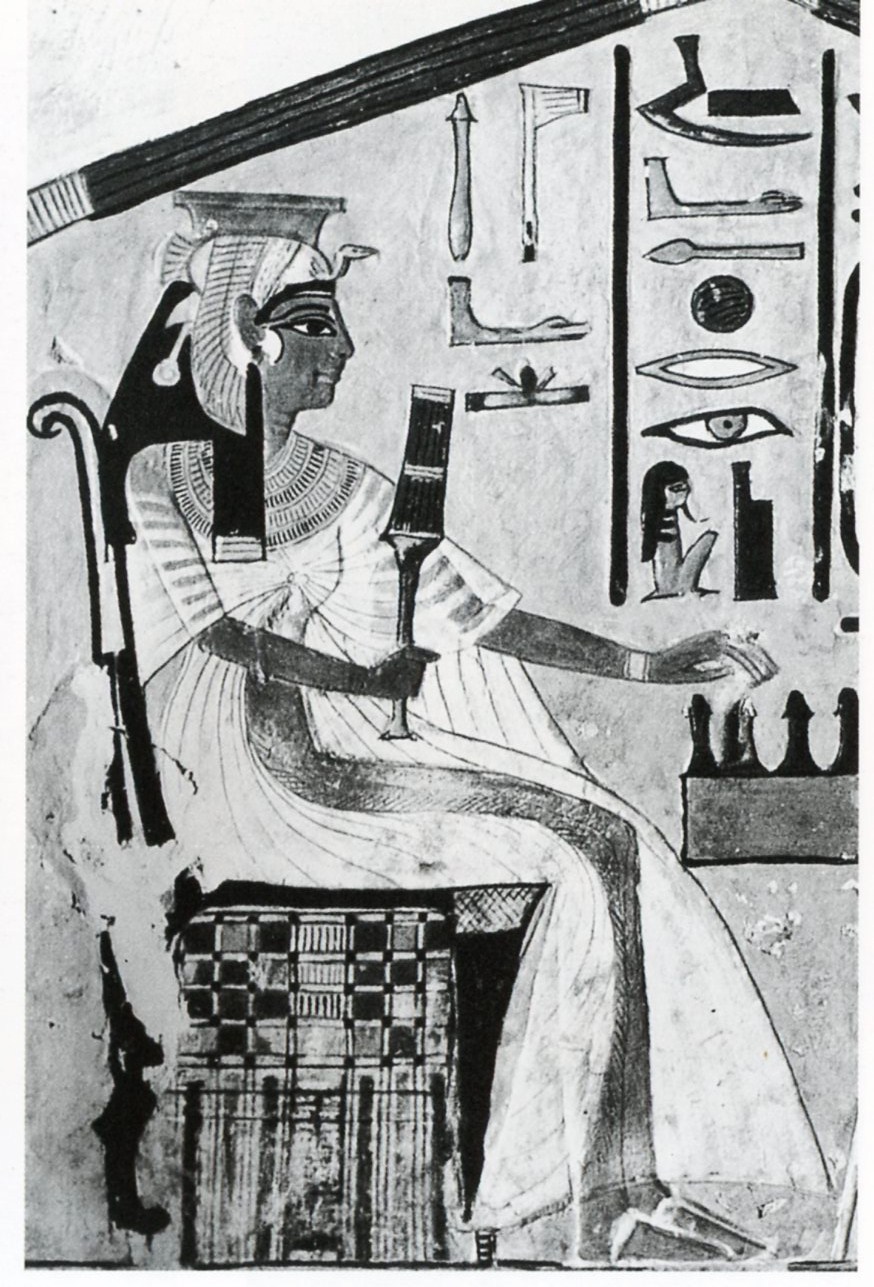

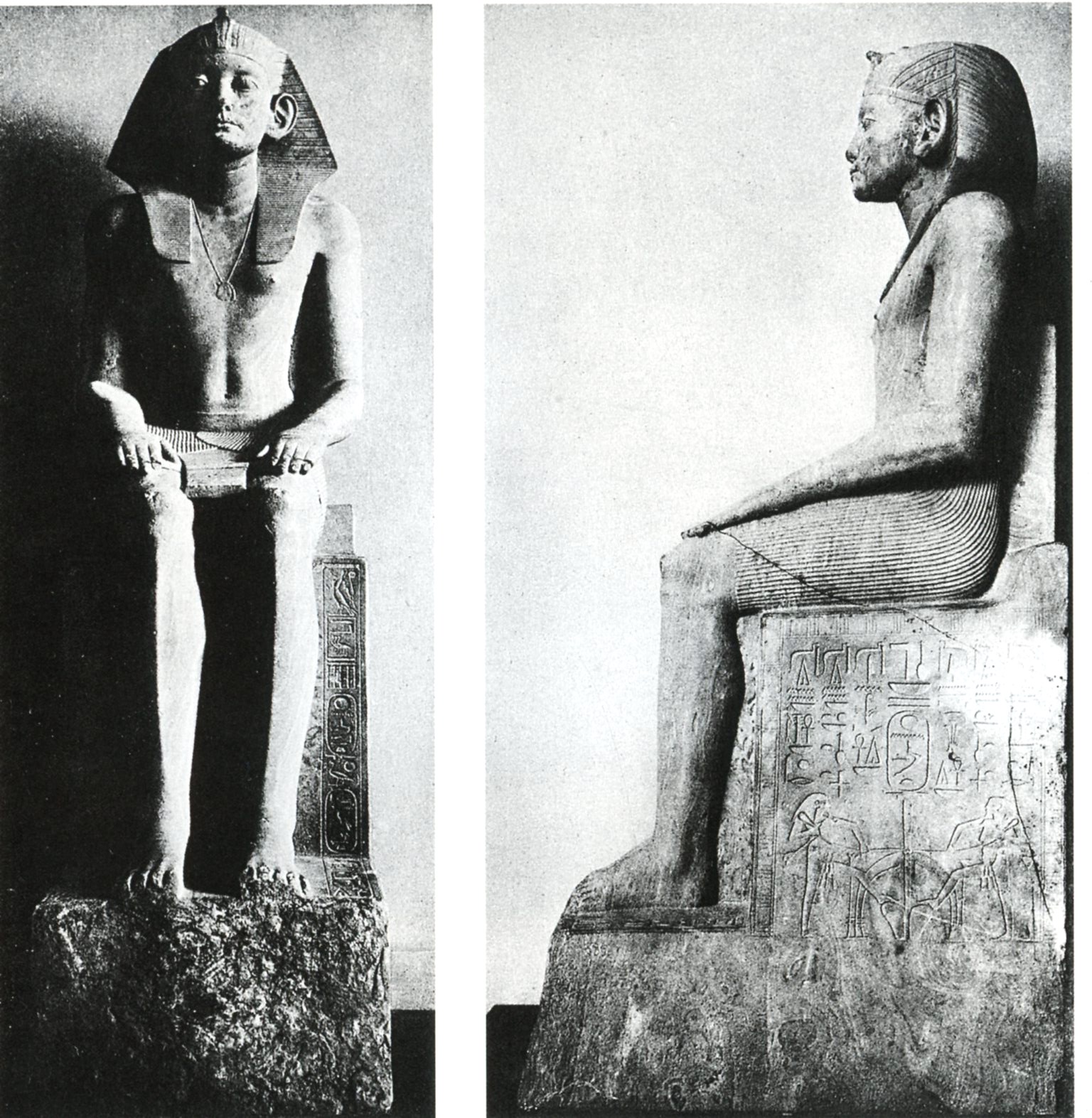

As Marinetti himself noted – writing “he [Depero] is lost among archaism and an ancient Egyptian frigid style” – ancient Egypt was an important reference point for Depero after World War I. Since 1917, the artist had clearly individuated the metaphysical implications of ancient Egyptian art. In Capri – where he stayed in the summer and early autumn of this year – Depero examined the photographic prints collected by Gilbert Clavel and, in turn, derived a new grammar for composing his paintings. In the Ritratto di Gilbert Clavel (Portrait of Gilbert Clavel; 1917; figure 17), the way the subject is sitting on an armchair reduced to a cubic box on a perfect axis, with his arm elegantly relaxed to the tips of his long, tubular and jointless fingers and impassive profile pushed to the foreground, recalls the typology of the seated figure in Egyptian art (figure 18).

Another typically Egyptian feature of his art is the manner in which he combined figures of different sizes not only in a singular compositional space, but also in the same plane. Moreover, photographs taken at the time that are dedicated to sculptures from ancient Egypt (figure 19) show statues whose frontal and side views coexist. This same concurrence of two points of view is exalted in Depero’s painting of Clavel. Perhaps noticing these qualities, young painter Filippo de Pisis, an acute observer of the Italian art scene, was the first to compare Depero’s works (seen in a group show, La Pittura d’avanguardia, at the Kursaal in Viareggio in August 1918) to “the scenes of certain Egyptian monuments, awesome, spectral, expressive precisely in their elegance and skeletal simplicity and in their ineffable rhythm.”13

Depero’s close attention to ancient Egyptian art is plain to see in his paintings of late 1918 and 1919: the forms in these works exhibit a notable plastic solidity, not unlike the quality of the masses one observes in Sironi’s drawings; though all balanced in a perfectly controlled arabesque, they likewise display disproportions in scale and have been arranged in absurd groupings that demonstrate an indifference for perspective. Combined with the theatrical elegance of Trecento and Quattrocento art, the precedent of ancient Egypt provided Depero with a mode of synthesizing the divergent stylistic paths of post-war Italian art.

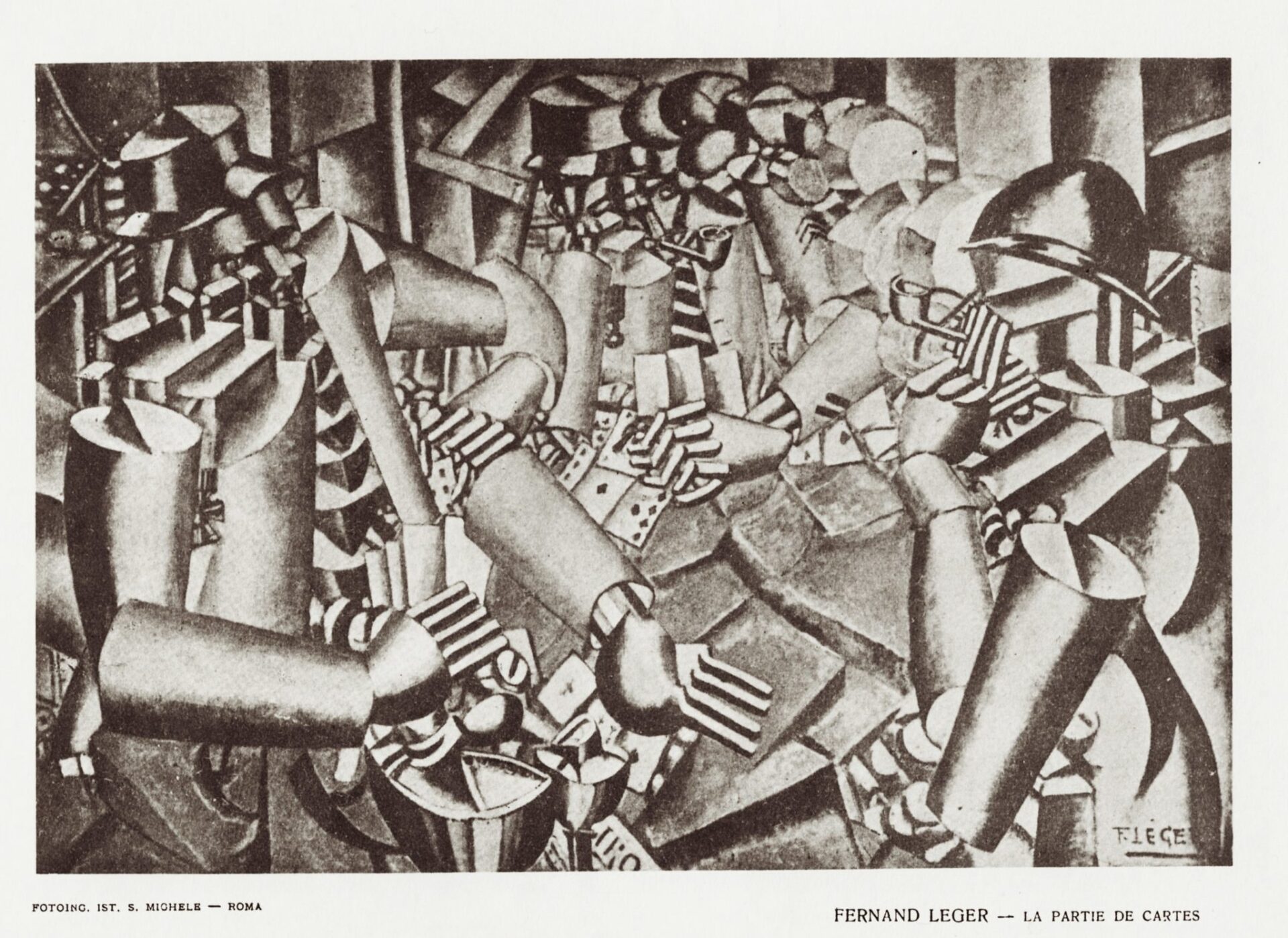

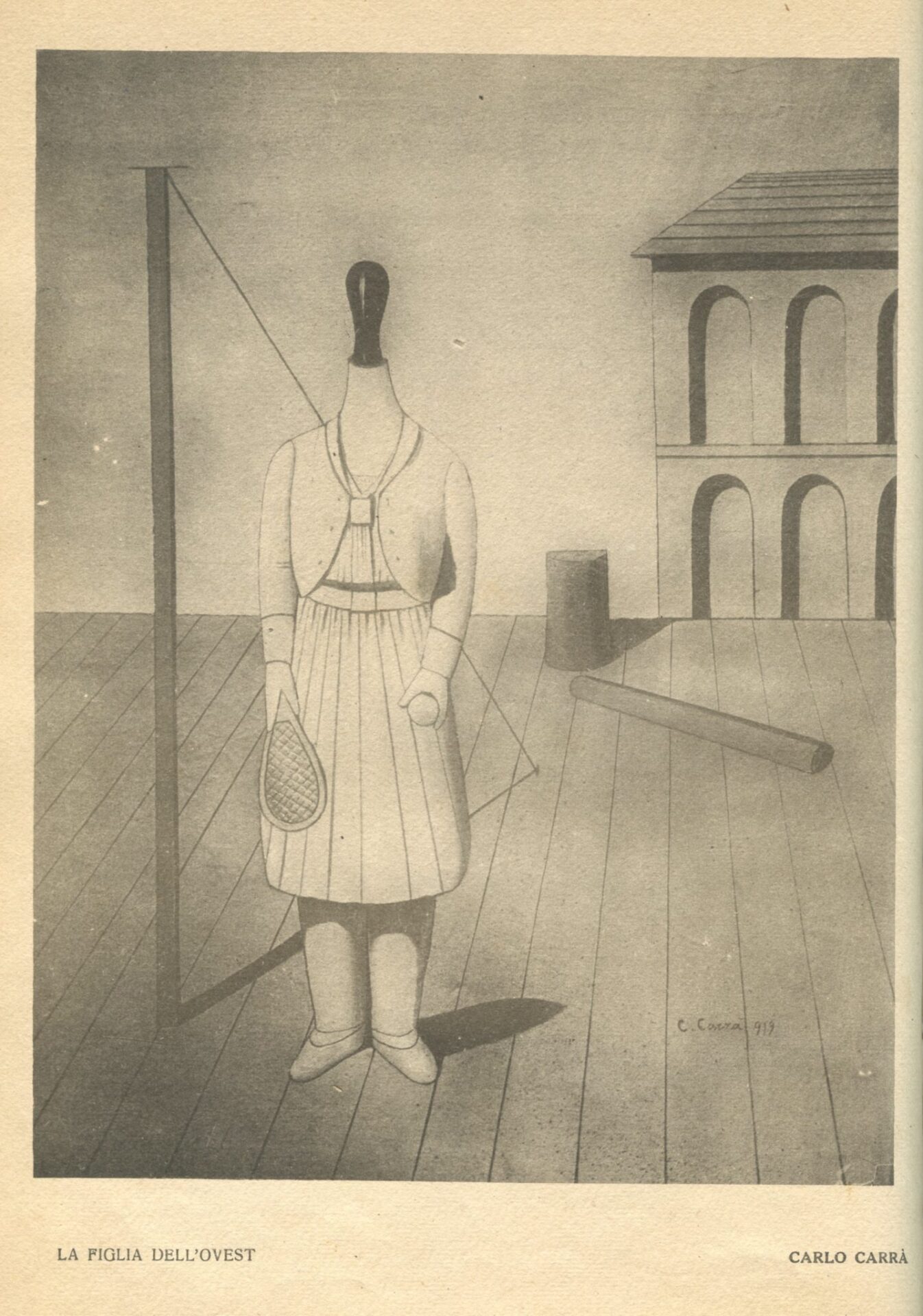

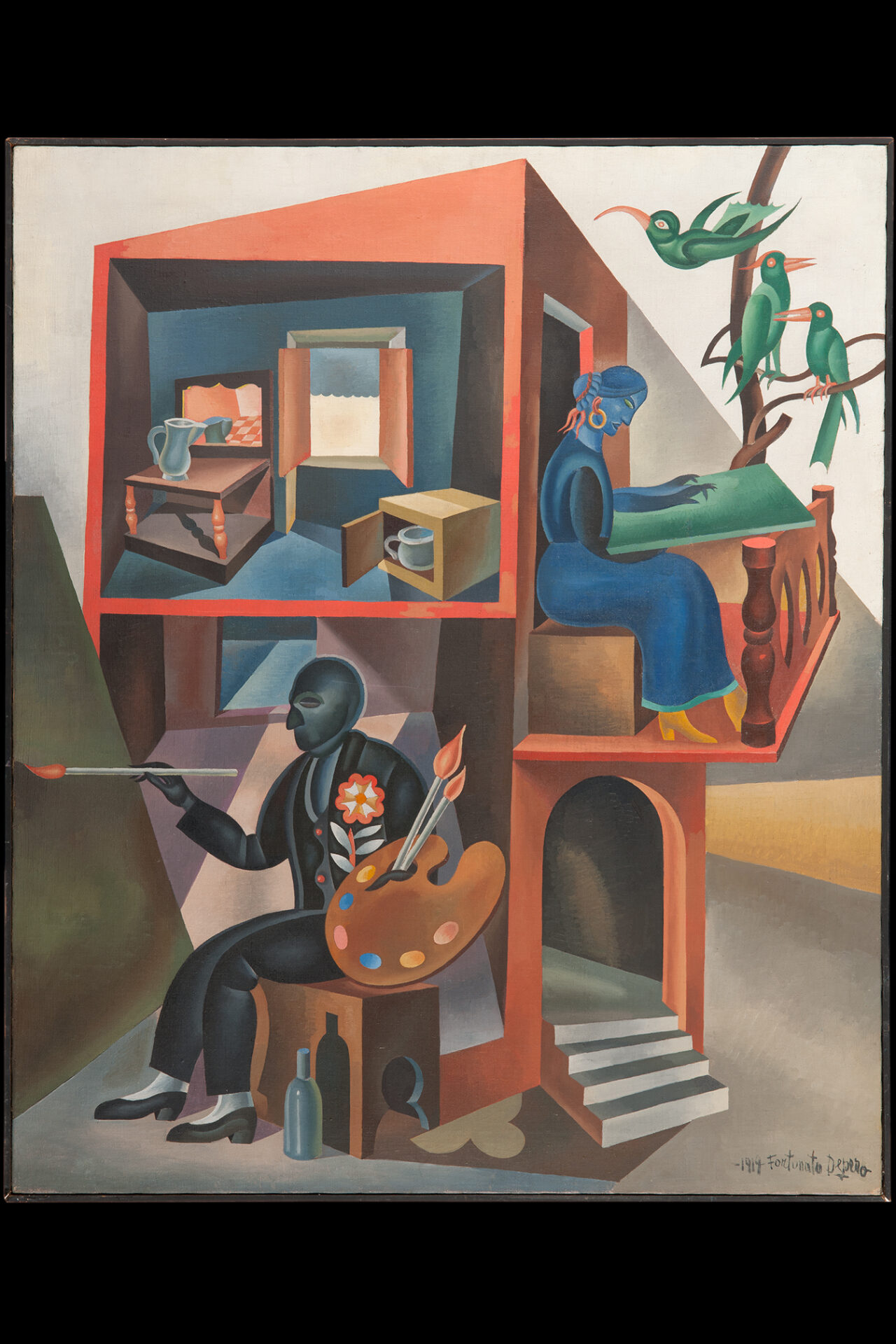

In mid-1919, the opposing alternatives for Italian avant-garde artists navigating the convulsive art scene came to manifest in two paintings, which appear here as black and white reproductions from several issues published in 1919 of the monthly art periodical Valori Plastici. On the one hand, one finds La Partie de Cartes (Soldiers Playing Cards) by Fernand Léger (in Valori Plastici I, 2–3, February–March 1919, front of p. 10; figure 20) with its mechanization of bodies and absurd repetition of gestures (and crowding of visual themes); on the other, one can see La Figlia dell’Ovest (The Daughter from Western Countries) by Carlo Carrà (in Valori Plastici I, 4–5, April–May 1919, front of p. 1; figure 21), which exhibits the vocabulary of the pittura metafisica (metaphysical painting) developed in a mysterious, primitive suspension and spatial rarefaction. Among all Italian artworks, only Depero’s 1919 oeuvre displays a convincing combination of these two aesthetics – that is, the language of Cubism and the subtle poetry of a newly conquered sense of space – with the formal precedents of archaic traditions.

Recall the comparison of Depero and Sironi that began this text. Depero’s 1919 Io e mia moglie (My Wife and I; figure 22) explicitly derives its design from Giotto’s Paduan frescoes: the modernist synthesis (both of colored surfaces and of spaces) meets a new and mysterious order of composition. The 1919 Interno di un caffè (Interior of a Bar) – which represents the grandiose triviality of modern life – was Sironi’s last confrontation with the inverted spatiality of Cubism (figure 23).

One year later, in March 1920, Sironi undersigned the Futurist manifesto Contro tutti i ritorni in pittura (Against All Revivals in Painting) and violently attacked the “modern archaic style” of recent Italian painting: the main object of this attack was Carlo Carrà and his archaic, neo-quattrocento painting Le figlie di Loth (The Daughters of Lot; 1919); however, Depero was displaced by Sironi into a field of an outdated language. Sironi firmly believed that the drama of the present times (the social postwar disorders and the diffuse atmosphere of waiting for Revolution) would be best represented by paintings that synthesized eloquent volumetric contrasts, violent chiaroscuro, and the logical disconnections of Futurism. By contrast, he relegated Depero’s sense of order, as well as his elegant and disengaged modernity, to the inferior field of decoration.

Bibliography

Cantù, A. “Dall’impressionismo del colore all’impressionismo della linea.” Vita d’Arte VI, XI, 64 (April 1913): 133–138.

De Pisis, Filippo. “La Pittura d’Avanguardia,” in XXVIa mostra del pittore futurista Depero. Rovereto: Mercurio: 1921. Exhibition catalogue.

Exhibition of the Works of the Italian Futurist Painters and Sculptors. London: The Doré Galleries, [1914]. Exhibition catalogue.

Grande Esposizione Nazionale Futurista. Quadri, complessi plastici, architettura, tavole parolibere, teatro plastico futurista e moda futurista. Milan: Galleria Centrale d’Arte, March–April 1919. Exhibition catalogue.

Longhi, Roberto. “Note d’arte. Al Dio ortopedico.” Il Tempo (February 22, 1919).

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. Taccuini 1915–1921. Edited by Alberto Bertoni. Bologna: il Mulino, 1987.

Rovati, Federica. Carrà tra Futurismo e metafisica. Milan: Scalpendi, 2011.

Sarfatti, Margherita G. “L’Esposizione Futurista a Milano. Terzo e ultimo articolo.” Il Popolo d’Italia (April 13, 1919).

Venturi, Adolfo. Storia dell’Arte Italiana. V. La pittura del Trecento e le sue origini. Milan: Hoepli, 1907.

Venturi, Adolfo. Storia dell’Arte Italiana. VII. La pittura del Quattrocento. Parte IV. Milan: Hoepli, 1915.

How to cite

Flavio Fergonzi, “Fortunato Depero in 1919,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/fortunato-depero-in-1919/, accessed [insert date].

- Mario Sironi, “Disegno. Dinamo Rivista mensile di arte futurista I, 4 (May 1919): 8.

- Exhibition of the Works of the Italian Futurist Painters and Sculptors, exh. cat. (London: The Doré Galleries, April 1914), 36, n. 5.

- A. Cantù, “Dall’impressionismo del colore all’impressionismo della linea,” Vita d’Arte VI, XI 64 (April 1913): 133–138.

- Fortunato Depero, reproduction of I fumatori di ferro, Il Mondo 5, 17 (April 27, 1919): 13.

- Which, unlike studies for paintings, are typically perceived as autonomous works.

- Grande Esposizione Nazionale Futurista. Quadri, complessi plastici, architettura, tavole parolibere, teatro plastico futurista e moda futurista (Milan: Galleria Centrale d’Arte, March–April 1919).

- Mostra personale di Fortunato Depero (Rome, Galleria Bragaglia, February 1919).

- Roberto Longhi, “Note d’arte. Al Dio ortopedico,” Il Tempo (February 22, 1919).

- Margherita G. Sarfatti, “L’Esposizione Futurista a Milano. Terzo e ultimo articolo,” Il Popolo d’Italia (Aprile 13, 1919).

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Taccuini 1915–1921, ed. Alberto Bertoni (Bologna: il Mulino, 1987), 400.

- Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’Arte Italiana. VII. La pittura del Quattrocento. Parte IV (Milan: Hoepli, 1915).

- Federica Rovati, Carrà tra Futurismo e metafisica (Milan: Scalpendi, 2011), 72–74; Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’Arte Italiana. V. La pittura del Trecento e le sue origini (Milan: Hoepli, 1907), 256; 351.

- Filippo de Pisis, La Pittura d’Avanguardia (1918 lecture), in XXVIa mostra del pittore futurista Depero, exh. cat. (Rovereto: Mercurio: 1921).