Metaphysics into Everyday Life: Traces of Metaphysical Painting in Italian Decorative Arts of the 1920s

Antonio David Fiore Antonio David Fiore Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

This study addresses the process through which, during the 1920s, Metaphysical painting was appropriated by some Italian decorators. I assume that they actively responded to the novelties that were introduced by artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, and Giorgio Morandi, reflecting upon them and, when considered effective, adapting them for their own purposes. By doing so, they contributed to the definition of a particular Italian visual culture, which today we associate with the interwar period, and which had Metaphysical painting as one of its main references.

A Metaphysical decoration?

In 1923, the first Mostra Biennale Internazionale delle Arti Decorative (Biennial Exhibition of Decorative Arts) opened in the Villa Reale of Monza, north of Milan. It was the first of a series of exhibitions that showcased the accomplishments of Italian artisans, manufacturers, architects, decorators, designers, and artists involved in the broad remit of the decorative arts.1 In subsequent years, the Monza exhibitions represented a regular occasion for the debate (often animated) of results, tendencies, and possible future achievements. A famed protagonist in these discussions was the art historian and critic Roberto Papini. In the prologue of a book gathering his comments on the first Biennale at Monza, Papini explained the aim of his work:

In our disoriented epoch, it represents an attempt at direction; with respect to a certain mentality imbued with Metaphysics, overintellectualism, and presumption, it wants to stand as a recall to logic and humility. We have been thinking about art in philosophical terms too much. In these pages, you will find neither complex disquisitions nor obscure cultural theories.2

Thus, Papini warned those engaging with the decorative arts against the decadent path taken by the fine arts, which were too intellectual, too affected by philosophical and literary sources of inspiration. He encouraged artists to embrace “logic” and “humility” instead.

Papini’s reference to “Metaphysics” is, I believe, specifically to Metaphysical painting. Indeed, although by 1923 the painters who had championed that movement beginning in 1916 had taken different paths,3 their particular shared aesthetic started to show its wider influence on many different expressions of Italian culture only in the first years of the 1920s. This study addresses one aspect of this phenomenon: the process through which – Papini’s warnings notwithstanding – Metaphysical painting was appropriated by some Italian decorators during the 1920s who were actively responding to novelties formulated in the fine arts, reflecting upon them, and adapting those they considered effective for their own purposes. In doing so, they contributed in the definition of a particular Italian visual culture, which today we associate with the interwar period and acknowledge as referential to Metaphysical painting.

By transferring iconographical solutions, atmospheres, and processes of Metaphysical painting onto objects and wall decorations, decorators facilitated the movement’s penetration into private and public spaces. Thus, it became part of an experience that transcended the canvas and involved objects. Ever since Giorgio de Chirico’s presentation of works by Giorgio Morandi in the Fiorentina Primaverile show in 1921, much has been written about what he called the “metafisica del quotidiano” (metaphysics of everyday life);4 this research concerns objects whose forms and decorative motifs brought Metaphysical painting into everyday life. It was the everyday life of a restricted elite, of course, and yet one which defined the taste of the time.

Tracking down the influence of Metaphysical painting upon the decorative arts is not an easy task. Both the artistic expression whose impact I am trying to assess and the field into which the objects that resulted from its impact fall are quite vague. Metaphysical painting is a highly difficult cultural phenomenon to pin down: It was neither a movement nor a school, and if for a short period of time there was a group, it was a lousy one (de Chirico famously called it “limited company”5); they had no shared manifesto, although a large amount of writings were produced as individual endeavors; even chronological boundaries are vague. Metafisica’s influence on other tendencies and movements was multifarious as, over the years, it transformed itself, went astray, and resurfaced anew. Meanwhile, the decorative arts encompass an extremely broad ensemble of creative practices whose relationship with the so-called fine arts is often ambiguous.

Indeed, the processes through which Italian decorators of the time appropriated Metaphysical painting were anything but univocal. My argument is that, in general, Metaphysical painting was approached as a “visual dictionary” of themes and solutions, and that these were borrowed and adapted while somehow their more controversial and challenging aspects were “defused.” At the same time, I believe that in some cases decorators engaged with the movement’s expression more profoundly: This is the case with Gio Ponti (1891–1979) in his early designs for the Richard Ginori ceramics. Ponti effectively transferred onto the surfaces and forms of objects and spaces not only the typical Metaphysical tropes and tricks (mannequins, paradoxical associations of objects, uncanny spaces), but also the irony, the anxiety, the sense of wonder, and the visual challenge that Metaphysical painters had championed, each one in a different way and according to a different agenda. Such communion of intent is not just a matter of taste: Ponti shared the idealist philosophical premises of the painters who had initiated the Metaphysical visual language, and their deeply ironic attitude towards reality.

I am not the first to reflect upon the response of the decorative arts to Metaphysical painting: Its traces in the decorative schemes and applied arts of the 1920s and 30s have been noted by a number of scholars, although never comprehensively investigated.6 Even contemporary critics and reviewers were aware of the spread of metafisica beyond the limits of painting. They turned to terms such as “dream,” “imagination,” “fantasy,” “escapism,” and “irony” – which I will often use in my analysis – in trying, for the first time, to make sense of these works. More recently, Renato Barilli, co-curator with Franco Solmi of the exhibition La Metafisica, gli anni Venti, stated: “During the 1920s, the Metafisica was an aura, sometimes very clear and intense, at others more impalpable; often, it got mixed up with aspects of a different nature.” He is insistent that this “field of investigation […] cannot be limited by the borders among the diverse arts and disciplines: The tensions and forces animating this field bypass such conventional distinctions. […] In fact, one should admit that the Metaphysical aura often revealed itself at its best in alternative ambits, with beautiful creations, concise and essential.”7

Such reference to metafisica, intended as an aura, allowed Barilli and Solmi to gather a variety of art forms, including those of the decorative arts. In analyzing this engagement, Rossana Bossaglia uses the working term “climate” to conceptualize the Metaphysical “lingering as an antecedent, a preliminary and indispensable hypothesis of investigation.”8 With all due caution, Bossaglia identifies recurrent elements in the Italian version of Art Deco – an “air of detachment, of quotation,” “an abstract and enchanted tone,” a “suspension of time and action” – which she interprets as derived from Metaphysical painting.9

This brief study draws on Bossaglia’s intuitions. However, I will try to overcome the consideration of the Metafisica as an aura or a climate, and focus instead on potential connections, responses, shared cultural motivations, and social and ideological exigencies and expectations. My aim is to select and analyze practices that, during the interwar period and in the field of the decorative arts, manifested what scholar Mario Ursino has defined as “the Metaphysical effect”: a clear aesthetic strategy aimed to generate a sense of suspension and discomfort in the viewer.10

Gio Ponti’s “Metaphysical” ceramics

In order to assess how Metaphysical painting’s modes were made available to decorators who, consequently, began using them consciously as a source of direct and indirect inspiration, we can turn to the main events and means through which Metaphysical art was promoted. Works by Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Giorgio Morandi were featured regularly in the magazine Valori Plastici between 1918 and 1922, and also in Giuseppe Raimondi’s La Raccolta. In the same period, solo and collective exhibitions of paintings and drawings by the same artists and Mario Sironi were organized, with catalogues featuring black-and-white photographs. These exhibitions, between 1917 and 1922, took place in Venice (1922), Florence (1921 and 1922), Rome (1918, twice in 1919), and Milan (1917–18, 1920, 1921, and twice in 1922). In addition, we have to consider also where the artists were based: During this period Morandi was, of course, in Bologna; Sironi was in Milan as of late summer 1919; beginning in 1917, Carrà was in Milan; and de Chirico was in Milan between 1919 and 1920. Considering this data, it should not come as a surprise if the first examples of objects bearing marks of ornamentation that, in an original way, “flirt” openly with Metaphysical painting were the creations of an architect, temporarily working as a decorator, based in Milan: Gio Ponti.11

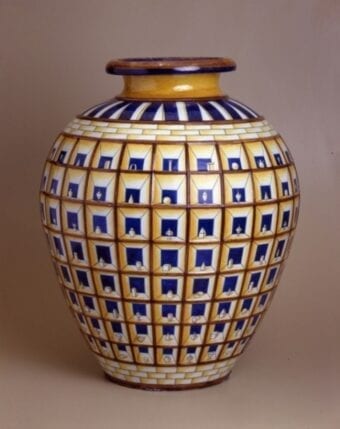

Back to Monza in 1923 and the first Biennial of Decorative Arts: Former Metaphysical painter Carlo Carrà, while walking through the rooms of the Palazzo Reale, noticed and appreciated the neoclassical and fanciful designs that Ponti had invented for the Richard Ginori ceramic company (figure 1).12 He did not label them “Metaphysical,” but this should not come as a surprise. By then, he himself had abandoned that phase of his career and distanced himself from his former friend de Chirico. Yet, he must have caught on the surface of those vases something familiar, that he appreciated.13 Indeed, although Ponti’s works shared the same classical sources of inspiration as the other presentations at Monza, they looked remarkably different.

When offered the role of artistic director at Richard Ginori in 1923, Ponti was given the opportunity to practically apply his ideas of a design that was respectful of tradition and, at the same time, immediately recognizable as modern. He found in Metaphysical painting a way of interpreting a repertoire in an original way that matched the expectations of his audience. De Chirico’s, Morandi’s, Sironi’s, and Carrà’s references to classical and early Renaissance art were obvious; it was how they were performing this process of re-engagement with tradition – through ambiguously designed perspectival space, paradoxically associated objects, the suspension of action, and irony – that was new. It must have appeared to Ponti a possible way of being modern, and he promptly snatched it up and made it his own.

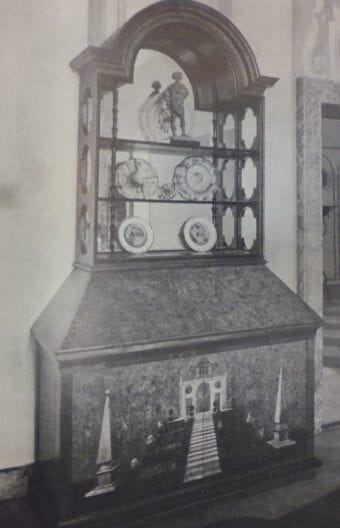

One of the most interesting pieces presented by Ponti was the Prospettica vase (figure 2), displayed prominently in the middle of one of two long walls in the room were the Richard Ginori ceramics were on display. Against a dark blue background, Ponti designed horizontal rows of square boxes, each of them foreshortened towards a central vanishing point according to the height of the row. Each box included an object – geometrical volumes or vases – while around the neck of the object itself vertical parallelepipeds and pyramids alternated. The reference to Metaphysical painting’s recurrent iconographies is quite evident; yet, this work shows a more profound engagement with the irony and taste for paradox that is typical of de Chirico’s art. The recurrent element that characterizes the ornament of this vase is the perspectival box, a typical Metaphysical device first used by Carrà, who borrowed it from Giotto’s frescos, as an enclosed stage for his compositions of mysterious, evocative objects. Ponti plays with the theme, multiplying the boxes. The fact that vases are pictured in them evokes the series of “paintings within the painting” that de Chirico developed starting in 1916, followed by Carrà. The vases in the boxes – used as decorative motifs – generate a rich visual paradox: Vases are presented on the vase; and, in the Richard Ginori room, the vase itself was presented among other vases; and that room was along a row of rooms where other Italian manufacturers were showing their ceramics. The repetition of the motif all around the circular shape of the vase visualizes a temporal dimension of continuity in the eternal variation of a theme (the object within a box). Finally, by showing the blue background through the boxes and the sequence of parallelepipeds and pyramids around the neck of the vase, the impression made on the viewer is one of a perforated surface: an ironic visual paradox, considering the vase’s function as a container.

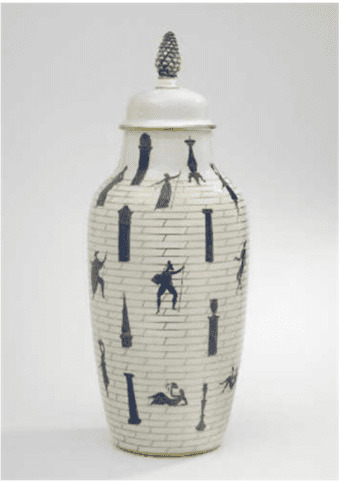

In a 1970s interview, Ponti stated that for him “everything is simultaneous – past, present, and future,” highlighting his fundamentally idealist philosophical approach to creativity; one that, once again, he shared with de Chirico.14 This idea of simultaneity, of an endless resurfacing of archetypal forms, is the concept behind, I believe, the urn called La passeggiata archeologica (The Archaeological Stroll, 1923; figure 3). On a slippery tiled floor – diagonally tilted, not foreshortened – Ponti’s design alternates vertical sculptural and architectural elements, such as candelabras, columns, and tombstones, with slim and elegant figures who wear period-appropriate costumes. The reference to classical antiquity is not philological; rather, Roman antiquity, the Renaissance, and Neoclassicism are collapsed together to express a synchronicity of creative tension. Indeed, the Passeggiata Archeologica was a park in Rome that included within its border a vast area from the Colosseum to the Fora, the Palatine, the Circus Maximus, and the Caracalla Baths. Together with the spectacular ancient ruins, remains from the Renaissance, Baroque, and Neoclassical periods coexisted, in what was a vivid and mesmerizing visualization of eternal processes of transformation of the same forms. On Ponti’s urn, walking among the remains of different epochs, the characters seem to establish a dialogue, the topic of which must be the meaning and significance of the recurrent return to classicism.

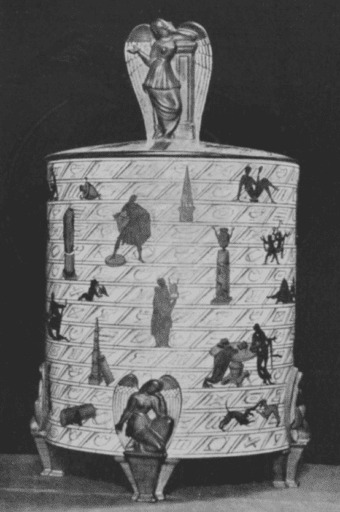

The vase called La conversazione classica (The Classical Conversation, 1925; figure 4) develops the same theme as La passeggiata archeologica. This modern cista was modelled after antique examples, in this case a kind of Etruscan container for jewels that is often cylindrical, with the main volume supported by feet and the lid crowned by a sculptural element. Ponti asked sculptor Libero Andreotti (1875–1933) to model the winged victories that decorate the feet and lid.15 This time, the figures animating the surface are placed together with columns, urns, candelabras, and sundials, against a patterned ground suggesting a mosaic floor (again tilted, not foreshortened) decorated with mysterious ornaments. This conversation is conducted in an enigmatic, mysterious language – almost esoteric. It is performed according to the rhythm of a sort of never-ending dance developing around the cylindrical shape of the container. The absence of a vanishing point has the same effect as the multiplication of the vanishing points in the Prospettica vase: Space becomes infinite and time suspended.

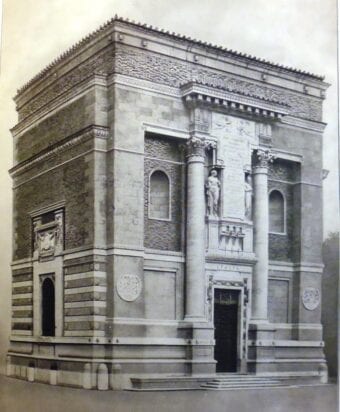

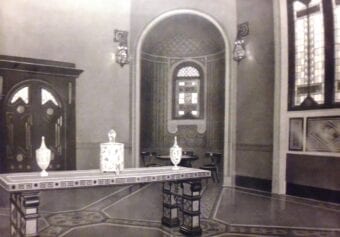

With these original inventions, Ponti managed to put Richard Ginori’s production back into the spotlight for critics’ and onto buyers’ lists. The interest and consensus were widespread, although some were a bit suspicious of Ponti’s peculiar way of engaging with tradition. It should not come as a surprise that Papini – who, as already discussed, had criticized the influence of “Metaphysics” – was among those who, although pleased with the modernization of the design, were not completely convinced of the way it was performed. Like the first Metaphysical works by de Chirico and Carrà, Ponti’s ceramics were accused of bearing the marks of foreign movements, mainly German and Austrian Secessionism and Symbolism.16 Indeed, Ponti’s contribution to the Italian Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Universelle des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) in Paris demonstrated how different his neoclassicism was from the one that was generally considered mainstream. The Richard Ginori ceramics were displayed in the main hall of the pavilion, among products featured as flagships of the excellence of Italian national production. The contrast between Ponti’s approach to classicism and that of architect Armando Brasini (1879–1965), as expressed in the latter’s pretentious design for the building, could not be more striking (figures 5–6).17

There are other instances that demonstrate Ponti’s consideration of Metaphysical painting. As is evident on some of his Richard Ginori plates, one of his favorite themes is the isolated figure placed in a strange space characterized by a low horizon and architectures either vertiginously foreshortened or flat. The scale of these figures is always disproportionately large with respect to the buildings, which look like theatrical backdrops, featuring refined and erudite quotations from Sebastiano Serlio’s and Andrea Palladio’s treatises. De Chirico’s Piazze d’Italia series (first elaborated in 1912, and developed throughout his career), as well as his mysterious Metaphysical totems, are obvious references here.18 Like de Chirico, Ponti designed his spaces as evocative, suggestive stages: They are ideas of places rather than real ones, the output of an architect’s dream. These imagery stages are populated by phantasmal presences, simplified figures strangely contorted and disarticulated like puppets. Borrowed from Mannerist sculpture and early-nineteenth-century illustrations, they often feature blank eyes or inexpressive faces. They are almost the equivalent of de Chirico’s Metaphysical mannequins, but Ponti could not resort fully to the original model, probably because of its overly anxious and uncanny connotations. One should never overlook the fact that, through the decorative arts, Ponti wanted to promote a design that could seduce wealthy clients with escapism, elegant style, and refined quotations. The enigmatic Metaphysical mannequin, with a blank face to disturbingly mirror the viewer’s own melancholy, was not an entirely suitable option, and needed to undergo a process of demystification.

As a result, Ponti’s figures are evanescent, gentle spirits, dematerialized and desexualized, like the adolescents of La casa degli Efebi (The House of the Ephebes; figure 7). The house evoked by the title as a space inhabited by ephebes is just a fragile, flat backdrop of softly wrapped draperies. Paradoxically – considering that Ponti trained and worked as an architect – weight and function are absent, challenging at least two of the three Vitruvian principles of architecture: Ponti’s house of the ephebes is all about beauty (venustas), while utility (utilitas) and strength (firmitas) are not contemplated. At the same time, the reference to the ephebes resounds with previous speculations developed by de Chirico and Carrà around the mythic figure of Hermaphrodite, as well as in the writings of Alberto Savinio (1891–1952; see his Hermaphrodito, 1918).19 The son of Hermes and Aphrodite was regarded by the Metaphysical artists as a superior being able to unify the female and male, Ariadne and Dionysus, intuition and creation. They were also very conscious of the potentially disconcerting effect that the evocation of a character, traditionally represented with more or less overt sexual connotations, could have on the public at the time, when represented as a cold and desexualized mannequin. Also Ponti’s ephebes – delicate masculine figures, suspended between puberty and sexual maturity – play with gender ambiguity. However, they are represented in a lazy abandonment, rather than as enigmatic deities: Their inaction does not puzzle the observer; they are just harmless decorative silhouettes.

Renato Barilli’s consideration of Ponti as the champion of a “sort of ‘normalized’ and enlarged Metafisica” becomes highly pertinent here.20 Additionally, one should not forget that Ponti’s engagement with aspects of Metaphysical painting was noticed by his contemporaries, such as Raffaello Giolli, one of the brightest art critics of the time. According to art historian Dario Matteoni, Giolli interpreted Ponti’s “enchanted silence and suspended space [as] part of a poetics that ranges from the Novecento to Metaphysical painting.”21 It is worth quoting Giolli himself:

[T]his is why, before almost all of Ponti’s works one stands still and daydreams, like reading a novel or a story: the mysterious story of the balloon liberated into the dark sky […] the allegorical novel of the house of the ephebes […] the fable of the beautiful women […] the dream of the Olympian metropolis, silent and abstract of the classical conversation.22

That the critic Edoardo Persico wrote, in 1929, that Ponti “might be linked to that twentieth-century taste, to Carrà and de Chirico,”23 also confirms that interpreting some of Ponti’s early designs for ceramics as responding to Metaphysical painting is not a completely far-fetched enterprise. The similarities I have highlighted testify to an awareness on Ponti’s part of what Metaphysical painters had achieved, and suggest that his aim was to appropriate and adapt iconographies that he must have seen as potentially modernizing.

Other traces of Metaphysical painting in Italian decorative arts of the 1920s

The subtlety and effectiveness with which Gio Ponti’s ceramics engage with Metaphysical painting remain, in my opinion, unsurpassed. However, in the work of contemporary creatives in the same field who were close to him, traces of an appropriation of certain solutions and iconographies of Metaphysical painting stand out. Even if the engagement that these designers were showing had diverse degrees of commitment, it demonstrates the de facto inclusion of Metaphysical painting in a canon, which although very recent, allowed other artists and designers to reinvent.

Yet, before examining Ponti’s followers and collaborators, I would like to discuss two works by Giovanni Muzio (1893–1982), who, like Ponti, was an architect who worked also as decorator. His works show a more complex attitude towards the lessons of Metaphysical painting. Together with Ponti and others, he was part of the so-called “Milanese neoclassicists.” They reinterpreted forms and compositions derived from the past, using classical decorative elements more as learned quotations and references than as active elements of the architectural composition. Thus, their designs were often characterized by a strange abstract appearance, very similar to the spaces used by de Chirico to stage his enigmatic revelations. Design historian Giampiero Bosoni defines the “Milanese neoclassicism [as] the heir of certain ventures of Metaphysical painting.”24

Muzio’s Via della Moscova building (designed in 1919, completed in 1922; figure 8) exemplifies this, with its strange arrangement of classical decorative elements ostentatiously attached, without practical function, to a vast façade. The effect was so confusing to contemporary viewers that the building has gone down in history as “the ugly house” (Ca’ brutta, in Milanese dialect). One element is of particular interest: the large arch that connects the two buildings that form the estate. Designed as an enormous serliana window with side openings surmounted by two portholes, it is an extraordinary episode of stripped-down classicism – so reduced to bare volume that it has the appearance of the monumental ghost of its Renaissance model.

Certain Metaphysical suggestions were not unknown to Muzio, who knew Carrà. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that, as reported by Annegret Burg, a reviewer for the newspaper Il Secolo wrote that “the lack of ability to design a straight line or a harmonious sign is balanced by the metafisica,”25 thus highlighting the architect’s approach rather than an iconographical influence. Indeed, Muzio’s reflection upon de Chirico and Carrà’s Metaphysical art has often been mentioned as a trigger for his new and unconventional classicism.26 References to the architecture of the past combined within suspended and estranged spaces migrated into Muzio’s furniture design, such as those for the intarsia for F. Ferrario’s furniture presented at the second Monza Biennial, in 1925; the landscape featured on the bottom section of a small cabinet (figure 9) evokes, in the rigid symmetry of the pyramidal composition dominated by an arch (recalling the Ca’ brutta), a mysteriously abstract space both welcoming (a grand staircase directly faces the viewer) and slightly uncanny.

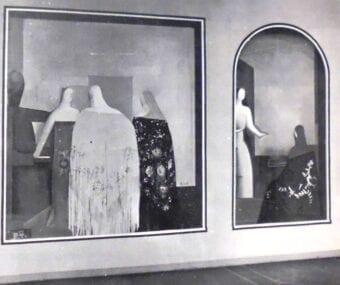

Let’s consider now several examples of contemporary decorators’ use of typically Metaphysical motifs. The mannequin, for example, became ubiquitous, and its most spectacular appearance in the realm of decorative arts was in two works, by Marcello Nizzoli (1887–1969) and Napoleone Martinuzzi (1892–1977) respectively. When, in 1925, Nizzoli was asked to arrange a display of shawls he had designed for the Piatti company, the ensemble formed a strangely unsettling composition, as shown in photographs from the time (figure 10). The section on the right-hand side was clearly indebted to Carrà’s Le figlie di Loth (Loth’s Daughters, 1919), a painting that, although showing the artist’s interest for a more early-Renaissance source of inspiration, was conceived during his Metaphysical period. In the section on the left, Nizzoli introduced a strange presence: another mannequin larger than the others, which recalls the puzzling mannequins that loom over de Chirico’s Metaphysical compositions, their faces disquietingly blank. In the context of the commercial display, the absence of physiognomic features had the obvious aim of focusing potential clients’ attention on the product (the shawls). Yet, these ensembles arranged by Nizzoli inevitably suggested an action, a narrative, which nevertheless remained enigmatic, just like the compositions arranged by de Chirico and Carrà and the disquieting nocturnal metropolitan interiors painted by Sironi during his Metaphysical phase. 27

Martinuzzi, for his part, portrayed an icon of 1920s culture, singer and dancer Joséphine Baker (1906–1975), as a huge glass mannequin about eight feet tall (figure 11). Ballerina (Dancer) was made out of individual elements attached to a metal framework, like a majestic Murano glass marionette. The green pulegoso glass pieces featured also red glass finishing.28 Presented at the glassmakers show in Venice in the spring of 1928, the mannequin was again exhibited that year at the Paris Salon d’Automne, where it impressed with its unconventional appearance.29 The giant statue looked like a hybrid creature, in between a Futurist female idol, and a Metaphysical, exotic deity landed in a faraway land. This work belonged to a space of coexisting diverse influences, which were, nevertheless, very typical of the period. Martinuzzi’s giant glass mannequin, while flirting with Metaphysical painting, also engaged with quintessential Futurist themes and approaches: the exotic and sensual ballerina, the use of unconventional media, a whole made out of the mechanical assemblage of fragments. So much so that, more than de Chirico’s mannequins, the robot-like automatons introduced by Sironi in his 1919–20 Metaphysical paintings come to mind.

Another artist whose Metaphysical phase Martinuzzi seems to have considered as a source of inspiration is Giorgio Morandi. In the same period that he created his dancer, the sculptor worked also on a series of small glass pieces representing succulent plants. Martinuzzi executed such designs also at monumental scale, for example for the Palazzo delle Poste di Bergamo (designed by architect Angiolo Mazzoni): The starkly contrasting colors combined with the impression of nature unnaturally frozen and blocked in its organic development – turned, as per enchantment, into a totem above and beyond time – all participate in a Metaphysical look (figure 12). Emily Braun has recently proposed that Morandi’s painting of a weirdly obdurate cactus that appears more mineral than vegetal (Cactus, 1919) was likely the inspiration for the obsession among Germany’s Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) artists for the cactus as a motif. It seems reasonable to think that the painting also had an impact on Italian contemporary artists, as well as on decorative artists such as Martinuzzi. Magic Realists and Surrealists, Neue Sachlichkeit and Novecento affiliates, as well as the second generation of Italian Futurists – they all borrowed elements from Metaphysical painting. So did decorative artists, producing works that participated in a wider general trend that characterized figurative art in Europe and the U.S. at the time. As claimed by historian, photographer, and art critic Franz Roh in 1925, the “best works of the new tendency display an inherent magic, spirituality, and uncanniness despite their composure and apparent sobriety.”30

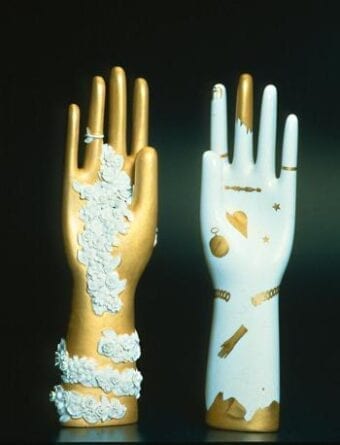

Such “inherent magic, spirituality, and uncanniness” is characteristic of much of the “modern” decorative arts produced in Italy by the most advanced decorators of the era. However, at the beginning of the 1930s, a shift becomes noticeable toward a further simplification of decorative motifs. While those supporting the stark forms of functionalism had begun spreading their objects in the rooms of the exhibitions, references to classicism persisted, but their evocation took form as either literal quotation or celebratory revival. Traces of the Metaphysical influence could still be detected, but less frequently. Indeed, during the 1930s, it was Gio Ponti who persisted in proposing objects that avoided the themes championed by the increasingly pervasive propaganda of the regime, and that still puzzled the public in displaying a fascination with the fantastic and, I believe, with the earlier output of the Metaphysical painters. The temptation to link his Mano della strega series (Witch’s Hand, started in 1935; figure 13) with de Chirico’s recurrent theme of the glove is too strong to resist. Indeed, the ceramic hands turned by Ponti into esoteric and refined objects were based on the mass-produced items that served as the matrix for the production of the rubber glove that we find in, for example, de Chirico’s Canto d’Amore (The Song of Love, 1915).

Conclusion

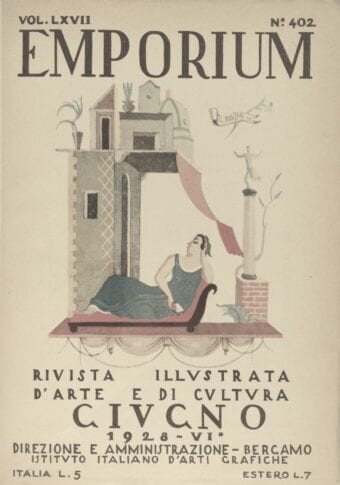

For his 1928 cover illustration for Emporium, decorator Giulio Rosso (1897–1976) used many of the themes that I argue were borrowed from Metaphysical painting and rearranged them to compose an amusing and delightful decorative scene (figure 14). A lady lying on a sofa is framed by architectural capriccio in the foreground; her eyes are closed, and her pose expresses introversion or daydreaming, maybe inspired by what she has just red in the book she holds in her right hand. Art historian Elena Pontiggia highlights how, sleeping ia “a typical Metaphysical theme, […] intended as a condition of immobility and suspension of existence.”31 Carrà’s L’idolo ermafrodito (The Hermaphrodite Idol, 1917) and L’amante dell’ingegnere (The Engineer’s Lover, 1921) both make the case for the importance of physical detachment from reality in order to reveal its mysterious and enigmatic side. In Rosso’s cover, space is incongruous too. The scale of the elements that form the architectural capriccio are inconsistent with the female figure and vases of succulents nearby; further, they are ambiguously foreshortened, like the backgrounds of a predella in an early Renaissance Italian altarpiece. Nevertheless, the reference to that early tradition is boldly challenged through the association of stark modernist volumes alongside architectural elements of the past, such as a dome. On the right-hand side, there is the detail of a classical statue on a pedestal, in a strange position, which resembles the iconography of Hermes as developed by Mannerist sculptors such as Giambologna or Benvenuto Cellini, whose works Rosso, who had trained in Florence, knew very well. Yet, these references – to self-absorption, the incongruous definition of space, and mythology – are reinterpreted in Rosso’s typically humorous way: They are curiously strange, but not unsettling; quirky but not uncanny.

Rosso was operating a process of demystification that, by liberating Metaphysical painting of its philosophical and literary premises, turned it into a repertoire from which the decorator could pick up solutions and atmospheres, and – sure of their modern appeal – playfully rearrange them. But we should not be fooled by the skilled appropriation performed by such decorators: As critic Margherita Sarfatti commented on the Italian participation at the 1925 Exposition Universelle des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the decorative arts provide witness of the taste of the time, and although decorators try to disguise the truths about their processes, implications, expectations, etc., those truths are still there for us to detect and understand.

Gio Ponti, Giovanni Muzio, Marcello Nizzoli, Napoleone Martinuzzi, and others reflected upon paintings by Giorgio De Chirico and Carla Carrà to locate possible solutions to a crucial dilemma of cultural debate at the time: how to design a modern object/ornament while reasserting continuity with local/national tradition. These decorators recognized in Metaphysical painting a way to promote traditional elements of a figurative approach to representation that, at the same time, was interpreted in an original way to resonate with its audience’s expectations. In the years following Metaphysical painting’s brief period, its influence on the decorative arts resulted in a dreamy and fantastic kind of revivalism. The painter’s achievement was in reconnecting the avant-garde with national tradition by reinterpreting the canonical elements of composition and narration; the decorators followed with similar achievements.

On the other hand, decorators were not interested in asserting the complex philosophical and literary sources of de Chirico’s art; indeed, their works were devoid of the subtle anxiety, or the personal memories and idiosyncrasies, with which the works of the painter of Vólos were imbued. In this way, Italian decorators were able to update the traditional repertoire while leaving aside more unsettling aspects of Metaphysical painting that did not befit the social functions that objects and ornaments perform when placed in buyers’ domestic environments. Through decorators’ re-elaboration, the Metaphysical vocabulary of iconographies and atmospheres participated in the shaping of contemporary taste, effectively finding a place in the everyday life of the elite.

Bibliography

Baldacci, Paolo. “Giorgio de Chirico e il ‘Novecento’ – alcune riflessioni.” In Novecento. Arte e vita in Italia tra le due guerre, edited by Fernando Mazzocca, 370–77. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2013. Exhibition catalogue.

Baldacci, Paolo, and Gerd Roos. De Chirico. Venice: Marsilio, 2007. Exhibition catalogue.

Baldasso, Franco. “Impossible Homecoming: Alberto Savinio and his ‘Hermaphrodito’.” Italian Modern Art, issue 2 (July 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/impossible-homecoming-alberto-savinio-and-his-hermaphrodito/.

Barilli, Renato. “La bomboniera metafisica.” L’Espresso 28, nos. 22–25 (June 13, 1982): 135.

Barilli, Renato, and Franco Solmi, eds. La Metafisica, gli anni Venti, vols. 1 and 2. Bologna: Grafis, 1980.

Barovier, Marino, ed. Napoleone Martinuzzi, Venini 1925–1931. Milan: Skira, 2013. Exhibition catalogue.

Bojani, Gian Carlo. L’opera di Gio Ponti alla Manifattura di Doccia della Richard-Ginori. Faenza: Marradi, 1977. Exhibition catalogue.

Bosoni, Giampiero, “Monumentality and Rationalism.” In Il modo italiano: Italian Design and Avant-garde in the 20th Century, edited by G. Bosoni, 141–45. Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Milan: Skira, 2006. Exhibition catalogue.

Bossaglia, Rossana. “Arti decorative e Decò.” In La Metafisica, gli anni Venti, vol. 1, edited by Renato Barilli and Franco Solmi, 145–49. Bologna: Grafis, 1980.

Carrà, Carlo. L’arte decorativa contemporanea alla prima Biennale internazionale di Monza. Milan: Alpes, 1923.

Cogeval, Guy, and Beatrice Avanzi, eds. Una dolce vita? Dal Liberty al design italiano 1900–1940. Paris: Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie; Milan: Skira; Rome: Palazzo delle esposizioni, 2015. Exhibition catalogue.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Giorgio Morandi.” In La Fiorentina primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze – catalogo delle opere esposte con cenni biografici e critici. Rome: Valori Plastici, 1922. Exhibition catalogue.

Fossati, Paolo. La pittura metafisica. Turin: Einaudi, 1988.

Frescobaldi Malenchini, Livia, and Oliva Rucellai, eds. Gio Ponti e la Richard-Ginori. Una corrispondenza inedita. Mantova: Corraini, 2015.

Giolli, Raffaello. “Saggi della ricostruzione: l’esempio della Richard-Ginori.” Emporium 70, no. 417 (1929): 149–62.

Matteoni, Dario. ed. Gio Ponti. Il fascino della ceramica. Milan: Silvana, 2011. Exhibition catalogue.

Papini, Roberto. Le Arti a Monza nel MCMXXIII. Bergamo: Istituto Italiano Arti Grafiche, 1923.

Pansera, Anty, ed. 1923–1930. Monza verso l’unità delle arti. Milan: Silvana, 2004.

Pansera, Anty. Storia e cronaca della Triennale. Milan: Longanesi, 1978.

Pica, Agnoldomenico. Storia della Triennale di Milano. 1918–1957. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1957.

Pisani, Mario. Architetture di Armando Brasini. Rome: Officina, 1996.

Pontiggia, Elena. Modernità e Classicità. Il ritorno all’ordine in Europa dal primo dopoguerra agli anni trenta. Milan: Mondadori, 2008.

Portoghesi, Paolo, and Anty Pansera. Gio Ponti alla manifattura di Doccia. Milan: SugarCo, 1982. Exhibition catalogue.

Roh, Franz. Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus. Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei. Leipzig: Klinkhardt and Biermann, 1925.

Tosini Pizzetti, Simona, ed. Sironi metafisico. L’atelier della meraviglia. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2007. Exhibition catalogue.

Ursino, Mario, ed. L’effetto metafisico 1918–1968. Rome: Gangemi, 2010. Exhibition catalogue.

Vinardi, Monica. “Libero Andreotti, Sirena.” In La forza della modernità. Arti in Italia 1920–1950, edited by Maria Flora Giubilei and Valerio Terraroli, 327–28. Lucca: Fondazione Ragghianti studi sull’arte, 2013. Exhibition catalogue.

How to cite

Antonio David Fiore, “Metaphysics into Everyday Life: Traces of Metaphysical Painting in Italian Decorative Arts of the 1920s,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- From 1923 to 1927, the Monza Biennale was held every two years; in 1927, this changed to every three years. In 1933, the show moved to Milan, where it has since been held in the Palazzo della Triennale built by architect Giovanni Muzio. On the history of the Monza Biennale and the Milan Trienniale, see Agnoldomenico Pica, Storia della Triennale di Milano, 1918–1957 (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1957); Anty Pansera, Storia e cronaca della Triennale (Milan: Longanesi, 1978); and A. Pansera, ed., 1923–1930. Monza verso l’unità delle arti (Milan: Silvana, 2004).

- Roberto Papini, Le Arti a Monza nel MCMXXIII (Bergamo: Istituto Italiano Arti Grafiche, 1923), 7. All translations from the Italian are by the author.

- However, one should remember that from 1922, after the ritorno al mestiere (return to craft) period, Giorgio de Chirico re-engaged with Metaphysical painting. In 1924, for example, he painted the Metaphysical masterpieces Le muse inquietanti (The Disquieting Muses) and Ettore e Andromaca (Hector and Andromache).

- Emphasis mine. See Giorgio de Chirico, “Giorgio Morandi,” in La Fiorentina primaverile. Prima esposizione nazionale dell’opera e del lavoro d’arte nel Palazzo del Parco di San Gallo a Firenze – catalogo delle opere esposte con cenni biografici e critici. Firenze, 8 aprile–31 luglio 1921 (Rome: Valori Plastici, 1922), 153–54.

- In Paolo Fossati, La pittura metafisica (Turin: Einaudi, 1988), 187.

- Even in the most recent overview of the development of the decorative arts in Italy between 1900 and 1940, the influence of Metaphysical painting was not fully investigated. However, some works by Gio Ponti and Tomaso Buzzi (1980–1981) were included in the metafisica section of the show, somehow anticipating the thesis of this study. See Guy Cogeval and Beatrice Avanzi, eds., Una dolce vita? Dal Liberty al design italiano 1900–1940 (Geneva and Milan: Skira, 2015).

- Renato Barilli, “Dalla Metafisica agli Anni Venti,” in La Metafisica, gli anni Venti, ed. Renato Barilli and Franco Solmi, vol. 1, (Bologna: Grafis, 1980), 9–10.

- Rossana Bossaglia, “Arti decorative e Decò,” in ibid., 145.

- Ibid., 145, 146, and 149.

- Mario Ursino, ed., L’effetto metafisico 1918–1968 (Rome: Gangemi, 2010).

- It must be noted that eminent art historian Paolo Baldacci considers the similarities between de Chirico and Ponti’s works as “probably” due to a common reference to German Neoclassicism or Biedermeier. Nevertheless, he refers to Ponti’s architecture, without mentioning the latter’s work as designer of decorative art. See Paolo Baldacci, “Giorgio de Chirico e il ‘Novecento’ – alcune riflessioni,” in Novecento. Arte e vita in Italia tra le due guerre, ed. Fernando Mazzocca (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2013), 374.

- Ponti had probably begun collaborating with the Richard Ginori company in 1922, because he was able to provide designs that were turned into works and presented on time for the opening of the 1923 Biennale. On this topic, see Paolo Portoghesi and Anty Pansera, Gio Ponti alla manifattura di Doccia (Milan: SugarCo, 1982); and Livia Frescobaldi Malenchini and Oliva Rucellai, eds., Gio Ponti e la Richard-Ginori. Una corrispondenza inedita (Mantova: Corraini, 2015).

- Carlo Carrà, L’arte decorativa contemporanea alla prima Biennale internazionale di Monza (Milan: Alpes, 1923).

- Gian Carlo Bojani, L’opera di Gio Ponti alla Manifattura di Doccia della Richard-Ginori (Faenza: Marradi, 1977), n.p.

- Monica Vinardi, “Libero Andreotti, Sirena,” in La forza della modernità. Arti in Italia 1920–1950, ed. Maria Flora Giubilei and Valerio Terraroli (Lucca: Fondazione Ragghianti studi sull’arte, 2013), 327–28.

- Raffaello Giolli, “Saggi della ricostruzione: l’esempio della Richard-Ginori,” Emporium 70, 417 (1929): 155.

- Armando Brasini’s neo-baroque architecture enjoyed much success in early twentieth-century Italy. Often chosen for important public commissions during the Fascist period, he was ferociously criticized by the modernist faction, and later forgotten. However, with the advance of Postmodernism, his architecture was reassessed and has become increasingly the subject of research by critics and historians. See Mario Pisani, Architetture di Armando Brasini, (Rome: Officina, 1996).

- Paolo Baldacci and Gerd Roos, De Chirico (Venice: Marsilio, 2007), 13.

- On Savinio’s poem Hermaphrodito (Florence: Liberia della Voce, 1918), see Franco Baldasso, “Impossible Homecoming: Alberto Savinio and his ‘Hermaphrodito,’” Italian Modern Art, 2 (July 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/impossible-homecoming-alberto-savinio-and-his-hermaphrodito/ (last accessed on March 25, 2020).

- Renato Barilli, “La bomboniera metafisica,” L’Espresso 28, nos. 22–25 (June 13, 1982): 135.

- Dario Matteoni, ed., Gio Ponti. Il fascino della ceramica (Milan: Silvana, 2011), 29.

- Giolli, “Saggi della ricostruzione,” 154.

- Quoted in Matteoni, Gio Ponti, 30.

- Giampiero Bosoni, “Monumentality and Rationalism,” in Il modo italiano: Italian Design and Avant-garde in the 20th century, ed. G. Bosoni (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Milan: Skira, 2006), 143.

- Quoted in Annegret Burg, “Ca’ Brütta 1919–1923,” website of the Fondazione dell’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori della Provincia di Milano, https://www.ordinearchitetti.mi.it/it/mappe/itinerari/edificio/313-ca-bruetta/41-giovanni-muzio.

- Barilli and Solmi, La Metafisica, gli anni Venti, vol. 2, 15.

- Simona Tosini Pizzetti, ed., Sironi metafisico. L’atelier della meraviglia (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2007).

- Vetro pelugoso is a glass characterized by the presence in the material of a myriad of tiny air bubbles.

- Marino Barovier, ed., Napoleone Martinuzzi: Venini 1925–1931 (Milan: Skira, 2013).

- Franz Roh, preface to Nachexpressionismus – Magischer Realismus. Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei (Leipzig: Klinkhardt and Biermann, 1925).

- Elena Pontiggia, Modernità e Classicità. Il ritorno all’ordine in Europa dal primo dopoguerra agli anni trenta (Milan: Mondadori, 2008), 159.