Shaping an Identity for Italian Contemporary Art During the Interwar Period: Rino Valdameri’s Collection

Caterina Caputo Caterina Caputo Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

Rino Valdameri (Crema 1889 – Milan 1943) was a lawyer, patron, collector, and great promoter of Italian art, who in the years between the two wars built up in Milan one of the most conspicuous collections of modern paintings and sculptures, playing a central role within the system of Italian art and collectors’ market. Valdameri’s initiation into the patronage world took place sometime around 1919, almost as a consequence of his political interests and involvement in the Regime: through his friend, Gabriele D’Annunzio, he began to deal in art and made his debut curating the great edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy with illustrations by painter Amos Nattini. In two decades, he assembled more than 450 artworks, which mostly includes artists Valdameri considered to be at the forefront of international modern art, such as Giorgio de Chirico. Through his collection, Valdameri aimed to contribute to shape an Italian contemporary art as well as create a national, and international, art market for it, so that particularly important were Valdameri collaborations with art dealers and galleries in Milan, such as the Milione Gallery and the Milano Gallery. In this article I partially reconstruct the history of this large collection, the collecting taste of Valdameri, as well as his relationship with influential figures of the Italian political and artistic scene in the interwar years.

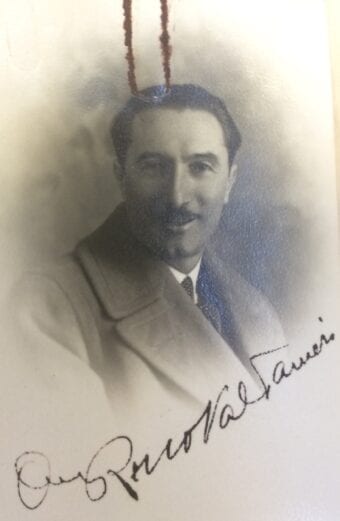

[He was] a skinny, pale young gentleman with a little brown moustache […]. We all wondered who he was: a certain lawyer, [Rino] Valdameri, the financier of a colossal edition of the Divine Comedy which was about to be published in a thousand numbered copies with illustrations by a painter, Amos Nattini. […] Valdameri’s patronage was not without self-interest. He aimed to turn it into a pedestal for himself in order to climb to a high social position in the field of art, and he got there.1

With these words, the Piedmontese writer Salvator Gotta introduced the lawyer Rino Valdameri (figure 1) into his memoirs, published at the end of the 1950s.2 Valdameri was a patron, collector, and enthusiastic promoter of Italian contemporary art who, in the years between the two World Wars, “dedicated the best part of his life to works of art and culture.”3 He was a character whom everyone knew in his time, but over whom a long silence descended after his death in 1943. The historical reasons for his oblivion were mostly due to Valdameri’s political involvement in the Fascist regime as well as the dispersal of his renowned art collection subsequent to his passing.

This study therefore intends to fill in the bibliographical gap and to historicize “one of the most conspicuous collections of modern paintings and sculptures in Italy”4 in the interwar period – a collection that played anything but a secondary role within the Italian art system and collectors’ market during Valdameri’s lifetime.5

Genesis of the Collection: The Legacies of the Nineteenth Century

Rino Valdameri was born in Crema on March 2, 1889, into a family of Lombard patriots. He began practicing law at an early age, after obtaining his degree in Genoa. His initiation into the world of art patronage took place sometime around 1919, almost as a consequence of his political ideas and involvement: he joined the National Fascist Party on September 20, 1922, and served on the fringes of the regime until 1943, the year of his untimely death.6

Through his friend Gabriele D’Annunzio, Valdameri began to deal in art and made his debut curating a colossal edition of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, illustrated by the painter Amos Nattini and published from 1921 to 1941 in one hundred issues (one for each canto).7 “I wanted to create a book,” Valdameri stated, “that from the technical and publishing point of view would be the most important in the world, constituting a truly monumental work,”8 a sort of “altar of the New Italy to the supreme poet [Dante].”9 The work, which required a huge financial effort and much time, was perceived by critics to be the result of “a resurrected patronage”;10 in order to spread the new ideals of “Italianness” and its matrices not only throughout the country but also abroad, the enterprise became a traveling exhibition that displayed the texts alongside original drawings by Nattini.11 The project summed up Valdameri’s two main preoccupations: politics and art.

The Divine Comedy edition was the springboard that allowed Valdameri to start a rapid rise up the political ladder in institutional sectors linked to culture.12 Thanks to the help of the Ministry of National Education, directed by Cesare Maria De Vecchi di Val Cismon and, later, Giuseppe Bottai, Valdameri presided over some of the most important institutions in Milan, where he had lived since the 1920s: from 1935 to 1940 he was appointed president of the Brera Reale Academy of Fine Arts and its annexed Liceo Artistico and Reale Scuola Superiore degli Artefici;13 in the 1930s he also directed the Poldi-Pezzoli Art Foundation, the Opera Pia Lombarda Croci,14 and, in 1938, the Società Dantesca Italiana (Dante Italian Society); further, he represented the Ministry of National Education at the Milan Triennale.15 In the period prior to these official assignments, Valdameri had been busy building a branched network of contacts with the leading figures of the official culture system; of particular importance was his relationship with Ugo Ojetti, at that time considered one of the most authoritative critics and writers in Italy.16

Ojetti’s aesthetic theories became an essential reference point in the artistic conception of Valdameri, who sought constant confrontation with and confirmation from the critic. Ojetti, in fact, was frequently invited to the lawyer’s Ligurian residence in Portofino,17 which, as of the second half of the 1920s, became the “almost continuous destination, for about fifteen years, of illustrious personalities of the arts;”18 Valdameri art collection was divided between his Ligurian residence and his main home in Milan, at Via Borromeo 7.

The programmatic line concerning contemporary art divulged by Ojetti in the pages of Corriere della Sera, Dedalo (1920–33), Pegaso (1929–33), and Pan (1933–35)19 was reflected by the lawyer in his ample personal interpretations, albeit with several deviations dictated by the art market and political ideology. Ojetti had always privileged artistic research based on a synthetic and balanced language, to the detriment of those practices that he decoded as “avant-garde intellectualisms.”20 According to the critic, the subject was the only way for the artist to reveal “his [own] spirit,”21 so the creative procedure (i.e., the technique) had to keep away from any expressionism: formal correctness alone allowed for true communication through representation. By assimilating these anti-modernist aesthetic conceptions and, in the same time, following Margherita Sarfatti’s ideas of a modern classicism,22 Valdameri came to personally appreciate nineteenth-century Italian art as well as contemporary trends characterized by a ricovery of artistic Italian traditions, such as Novecento Italiano (supported by Sarfatti) and Valori Plastici groups.23 The collection, as a whole, reflected the modern collecting practice spread in Northern Italy in the interwar years, representative of the new upper-class’ cultural models that found in commercial art galleries the reference point to their art patronage.24

Interpreted in the light of Ojetti’s aesthetic theories, Valdameri’s collecting practice opened up with a significant canvas (figure 2): “I began collecting with [Gaetano] Previati’s Viaggio nell’Azzurro [Travel to the Blue, 1895] purchased from the Associazione Mutilati that put on the exhibition. The initial cost was 16,000 Lire.”25 Ojetti’s interest in Previati’s work emerged in both his art collecting and his writings.26 The artist, who was also theorist of Italian Divisionism, in the 1920s was well appreciated – mostly for the spiritual values of his compositions – by both artist,27 critics, and collectors, as testified to the successful auctioning of his works.28

Valdameri, like many collectors, often acquired paintings at auctions held in private galleries: he bought Previati’s Viaggio nell’Azzurro in 1927 from the Pesaro Gallery in Milan, an exhibition space that strongly contributed to the shaping of taste among the more traditionalist bourgeoisie around the city, and that was linked to the origins of Margherita Sarfatti’s Novecento group. An exhibition of Previati’s art closed with an auction of his paintings that Lino Pesaro, the gallery’s owner, had donated to the Associazione Nazionale Mutilati ed Invalidi di Guerra.29 This event is significant for two reasons: it highlights Valdameri’s initial interest in the artistic trends of the late nineteenth century, and it reveals the sales circuits the lawyer followed for his first acquisitions.30 Viaggio nell’Azzurro is a painting that acted as a conjuncture between the nineteenth-century nucleus present in Valdameri’s collection and the conspicuous twentieth-century part.

The corpus aimed to give to Italian art its artistic primacy dismissing any foreign influence, especially the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, whose paintings were circulating widely in the broader European art market.31 The reasons for this gap can be explained by the patriotism and national inclination that had fostered Valdameri’s patronage from its earliest stages, when he decided to finance Nattini’s edition of Dante’s narrative poem.

The nineteenth-century portion of the collection was created in the wake of a historical review conducted by a large group of critics at the beginning of the century – in primis Ojetti, but also Enrico Somaré and Ardengo Soffici.32 Their findings were widely circulated through arts and literature magazines, including L’Esame, Dedalo and Emporium.33 These publications shared not only theoretical texts with readers, but also an extensive iconographic apparatus that retraced the formal and figurative tradition of Italian art in dialogue with the most contemporary of experiences. This renewed attention found an official voice at the Sixteenth Venice Biennale, in 1928, where an exhibition organized by Ojetti with critics Nino Barbantini, Emilio Cecchi, Ezechiele Guardascione, and Antonio Maraini was dedicated to nineteenth-century Italian painting;34 spanning from Macchiaioli and Scapigliatura to Divisionism, it emphasized the national roots of these movements and the “balanced harmony”35 of Italian art . It was this climate that gave rise to Valdameri’s interest in late nineteenth-century painting, especially artists who worked in Lombardy: he showed a preference for the painters of the Scapigliatura and Divisionist movements, including Giovanni Carnevali (known as Il Piccio) and Daniele Ranzoni, but also Emilio Gola and Antonio Fontanesi, put in dialogue with contemporary artists such as Carlo Carrà, Giorgio de Chirico, Pietro Marussig, Giorgio Morandi, Mario Sironi, and others:36 the aim was to shape an idea of “Italianness” in art based both on aesthetical values and ethical ones. More than a decade after first buying art, Valdameri declared that his collecting had “a sort of political purpose aimed at representing in a certain way the customs in that vast field that is modern art.”37 However, beyond developing a narrative discourse, the corpus had an additional objective: creating economic value in order to support an “international art market for Italian [contemporary] art.”38

Metaphysical Painting and the Art Market in the 1930s

In 1942, Valdameri declared in an interview released in the journal Quadrivio:

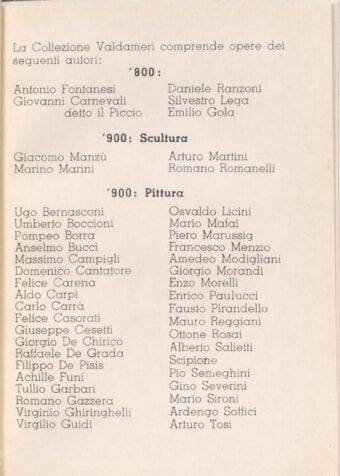

[My collection includes] four hundred and fifty paintings, seventy pieces of sculpture, about thirty engravings and drawings, divided as follows: [Giorgio] de Chirico 60 works; [Giorgio] Morandi 30; [Amedeo] Modigliani 3; [Piero] Marussig 110; [Carlo] Carrà 33; [Filippo] De Pisis 50; [Arturo] Tosi 30; [Achille] Funi 15; [Massimo] Campigli 15; [Ugo] Bernasconi 25. As regards the sculptures, 25–30 pieces by Arturo Martini (almost all of his production), and works by Marino Marini, [Giacomo] Manzù, and [Romano] Romanelli.39

At that time, he therefore owned more than five hundred paintings, sculptures, and some drawings – an exorbitant number that, in quantitative terms, brought his corpus much closer to the stock of an art gallery than that of a private collector. But for Valdameri collecting was synonymous with accumulating, which meant acquiring the greatest possible number of works of a favorite artist; it is no coincidence, then, that he reprimanded his Brescian colleague Pietro Feroldi, who was also a lawyer and collector of contemporary art: “[Feroldi’s collection] is far too small and loses the character of a collection.”40 The possession of massive quantities of artworks was a practice that had characterized Valdameri’s art patronage ever since 1928, when he entered a contract with Nattini for the execution of the Dante plates, becoming the exclusive owner of the original drawings (one hundred) and only paying the artist a royalty against sales of volumes.41 Although Valdameri was not an art dealer tout court, he acted as a merchant gathering a copious number of artworks and pursuing speculations; as he stated: “I am for established [artistic] values, otherwise it fails my aim to operate for the propaganda of an international market for Italian art.”42 The lack of a clear aesthetic canon advocated by the regime allowed Valdameri to choose artworks independently, following his personal taste, patriotism, and market trends set forth via auctions and galleries.43

Over the years Valdameri’s collection increased at an exponential rate through an intense and continuous purchasing campaign that he conducted thanks to the mediation of art dealers active in Milan, especially Count Vittorio Emanuele Barbaroux, and the Ghiringhelli brothers, respectively the owners of the commercial exhibition spaces Milano Gallery,44 and Il Milione Gallery.45 Of particular importance was Valdameri’s relationship with Barbaroux.

Valdameri began to spend time with Barbaroux at the Milano Gallery, where many modern art collectors got their training.46 However, their first real commercial collaboration dates back to 1933, when together they decided to sign up the sculptor Arturo Martini, who was to receive, in exchange for the production of works, a monthly cheque, and, in the case of sales, royalties.47 The managerial methods adopted by Barbaroux – and consequently also by Valdameri – were characterized by a marked pragmatism and intransigence with regard to the agreements, as Martini testified in a letter sent to collector Natale Mazzolà: “Since it seems I speak another language with businessmen, and since I do not understand it, I beg of you, and grant you the broadest mandate, to deal with Mr. Valdameri and Mr. Barbaroux. […] I believe that this union prohibits me from creating.”48 The artist’s impatience with the rigid rules he had to abide by was exacerbated when he was faced with the Barbaroux-Valdameri duo’s constant requests for the casting of sculptures to put in the market, even nonrecent ones, which risked lowering the commercial value of Martini’s entire production.49 The presentation and immediate acquisition of conspicuous lots of artworks was a commercial strategy of Barbaroux and Valdameri and not limited solely to Martini; instead, they applied it to numerous artists, first and foremost Giorgio de Chirico.

In the second half of the 1930s, the works of the father of Metaphysical painting became prominent on the Milanese collecting circuit, so much so that upon his return from the United States (where he had spent a year and a half), de Chirico received his main commissions from Milan; as the artist explained in a 1938 postcard to the American gallery owner Julien Levy:

I’m in Paris for a few days. Here the prices of my paintings have gone up considerably. In general, my position in Europe has risen 100%. Just imagine, I have received nine commissions in Italy in the space of a week. I am going back to Milan now to carry out several orders.50

Some of the factors triggering the sudden demand on the Italian art market for de Chirico’s Metaphysical works were seated in the international success of the artist’s early paintings and the consequent unavailability of his production on the market, resulting in their dramatic rise in price.51 Thus, in the 1930s, when works arrived on the market from an important Italian collection rich in Metaphysical paintings and drawings (Mario Broglio’s collection), art dealers and collectors rushed to buy them.52 In the years between 1937 and 1940, the works in question were mostly sold in several lots at both the Barbaroux and the Milione galleries, thanks also to Valdameri, who increased his art market speculations relying on these galleries.53

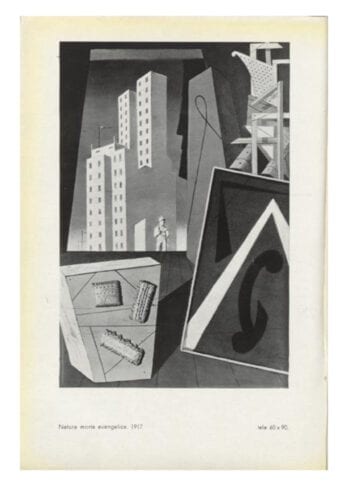

Among the most significant of de Chirico’s Metaphysical canvases owned by Valdameri – in addition to the Trovatore (Troubadour, 1917)54 – was certainly Natura morta evangelica II (Evangelical Still Life, II, 1917),55 (figure 3) which was the most expensive piece in all of Valdameri’s collection.56

The painting was on view in 1939 at the Milione Gallery, in an exhibition of works from de Chirico’s Metaphysical period that was not geared toward making sales, as most of the paintings had already been sold to interested collectors in small lots before it even opened.57 Barbaroux had taken an active part in these sales prior to the opening, often with the help of de Chirico himself,58 as Feroldi revealed:

Gino Ghiringhelli and I have discovered that de Chirico himself put paintings up for sale through Barbaroux (who claims he acquired them from an unnamed family), two small Italian piazzas and a Metaphysical one, the latter signed and dated 1914. However, the Metaphysical painting and one of the Italian piazzas were painted three months ago in VICHI.59

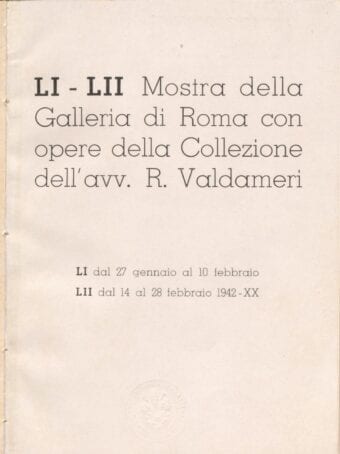

The word “Vichi” is instead “Vichy,”60 the city in France where de Chirico had gone to the thermal baths since 1911 in order to recover from health issues, and where the painter spent some time during the summer of 1939 before going back to Italy.61 Although, Feroldi’s assessment cannot be verified, in the thirties De Chirico’s backdated works began to circulate together with those of the current decade, both in Italy and abroad, and Valdameri himself had several in his collection, including Piazza d’Italia II (Italian Piazza II, 1933)62 and Malinconia Torinese (Torinese Melancholy, 1939).63 A large number of these Metaphysical paintings were on display in the exhibition that the Galleria di Roma dedicated to Valdameri’s collection in 1942 (figures 4 and 5), in which 250 works (including 50 De Chirico’s paintings)64 were presented to the public in two shifts, with a catalogue by Massimo Bontempelli.65

Contemporaneous reviews of the exhibition evidenced the critical debates concerning Metaphysical painting since the twenties, in particular with regard to its formal values. The critique was strongly influenced by Roberto Longh’s seminal article of 1919, in which the critic sided against De Chirico’s Metaphysical “illustrating” works;66 an opinion strengthened in 1935 by Carlo Ludovico Ragghinti, who stressed the lack of pictorial concerns of De Chirico’s early paintings,67 meanwhile, Cesare Brandi recognized in de Chirico’s Metaphysical works a modern pictorial interpretation of forms and a new artistic analysis of the reality.68 The exhibition at the Galleria di Roma triggered different opinions about the Methaphysical art as well as the Valdameri collection: in Emporium, Giancarlo Cavalli sided in favor of Carrà and Morandi, denigrating de Chirico’s Metaphysical artworks (“an implicit judgement of poetry in one case [Carrà and Morandi], and of no poetry at all in the other [de Chirico]”69); whereas his colleague Attilio Crespi paid homage to private collecting as a “testimony of trust in our contemporary art.”70 In contrast, critic Carlo Belli – a supporter of abstract art at the Milione gallery and Feroldi’s mentor – launched a harsh attack, criticizing not only the collection and its display, but also the too large amount of works:

We can find, especially in Carrà and de Chirico, a disconcerting discontinuity, painful drops, and sluggish recovery, […] a qualitative choice instead of a quantitative demonstration would undoubtedly have been of far more service to the art of our times in general, and to the collection in particular.71

Belli then added (but would erase these penciled words): “It can be observed how the ‘Metaphysical’ moment of these painters [Carrà, de Chirico, and Morandi] is not sufficient for justifying their fame.”72 Gino Severini also wrote a text in which he denigrated Metaphysical paintings as literary Metaphysics (“metaficismo letterario”), which is landlocked without any artistic way out, and the exhibition – he wrote – “was revealing for its lack of any purely pictorial concerns, […] in the pure sense of style and true poetry of form and color.”73 Valdameri’s collection was mostly criticized for not providing an exhaustive overview of the Italian contemporary art scene and for a lack of method in selecting works of art. This reproach was confirmed by the second part of the exhibition, with paintings by Ugo Bernasconi, Filippo De Pisis, Massimo Campigli, Felice Casorati, Achille Funi, Emilio Gola, Virgilio Guidi, Arturo Martini, Ardengo Soffici, Ottone Rosai, Mario Sironi, and others. Significantly, Minister of National Education Giuseppe Bottai opened the second show, on February 22.

Bottai, at the end of the 1930s, had launched an important legislative plan for art, resulting in the establishment, in January 1940, of the Office for Contemporary Art.74 Between 1938 and 1942, he wrote a series of articles aimed to clarify the position of the state with regards to art: “Problems related to art are part of the general issues [of the state], […] secondary […] but fundamental.”75 Bottai wanted to offer greater support to artists as well as collectors;76 the latter he considered “the best collaborators for the state in its actions for contemporary art” and indispensable “for ensuring that the work of individual artists helped to create a taste and to define a cultural plan.”77 Valdameri supported Bottai’s cultural objective,78 and through his collection tried to embody the Minister’s ideals by shaping an identity for contemporary Italian art; he stated: “in Italy we have great artists of international fame, […] able to compete with Braque, Picasso, Derain, Utrillo. The primacy [of art] should be assigned to Italian art, in particular to Morandi, de Chirico, Carrà, and Tosi.”79 Emblematically, in his article “Fronte dell’arte” (“Front of the Art”, 1941), Bottai referred to Carrà, de Chirico, and Morandi as artists who discovered a new relationship between ethics and aesthetics that was “definitively the highest contribution given by Italian art to world civilization.”80 Bottai’s instrumental rhetoric looked at contemporary Italian art as an example of ethics and political consciousness; in doing so, it decontextualized and semanticized artworks to attribute new artistic and historical meaning.

Epilogue

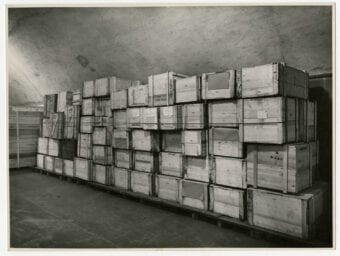

During World War II, Valdameri, like many Milanese collectors – for instance, Maria and Emilio Jesi, Franco Marmont, and Adriano Pallini – stored his art holdings away in a safe place, depositing them at the Sforzesco Castle. The Valdameri collection stayed there, in subterranean vaults (figure 6), until the exhibition at the Galleria di Roma was arranged.81 After the exhibition closed, the corpus likely remained in Rome, awaiting to be collected,82 but Valdameri died unexpectedly from septicaemia on May 29, 1943, just two months before the fall of Mussolini and the election of General Pietro Badoglio as head of state.83

After Valdameri’s death, the collection remained with his widow, Amelia Sala,84 arousing considerable concern in the art market and collecting world. Pietro Feroldi wrote to Venetian art collector and dealer Carlo Cardazzo:

I immediately thought of the financing group (more than ready) in order to prevent the collection from being sold; but I observed that as there was the minor [Valdameri’s son Edilio] (seventeen years old), a restraint was placed on it thanks to the magisterial inventory. For the time being, therefore, there’s no urgency. However, it will certainly be necessary to keep on an eye on that woman (the widow) [Amelia] as she immediately demonstrated rather bizarre behavior [with regards to Valdameri’s art collection].85

All apprehension soon subsided, however, because within a few months Valdameri’s wife was accused of having supported the political coalition of General Badoglio against Mussolini’s Italian Social Republic (Republic of Salò),86 for which she was arrested by the Nazis and deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she died.87

In 1944, the core of the collection was inherited by Edilio Valdameri, who was still a minor; as soon as the legal issues were cleared up, around 1947, the collection was gradually placed on the market to support the financial needs of the heir. The merchants involved were Valdameri’s former collaborators and friends, first and foremost Barbaroux. During the 1940s, many works were sold to collector Carlo Frua de Angeli, however, other figures, perhaps coming from the “financial group” that Feroldi had mentioned in his letter to Cardazzo, probably also took part in selling and buying pieces.

The Valdameri collection was gradually reduced in size, but not totally: some paintings were kept by the heir and new acquisitions were made, for instance, Felice Casorati’s painting Natura morta con testa di gesso e libri (Still Life with Plaster Head and Books, 1945–46).88 After the war, that canvas and others in the Valdameri collection were displayed in the exhibition Quarante ans d’art Italien, du futurisme à nos jours (Forty Years of Italian Art, From Futurism Until Today), held in Lausanne at the Musée Central des Beaux Arts in 1947:89 it was the last time that a conspicuous number of artworks from the Valdameri collection was exhibited.

In conclusion, the dispersal of the Valdameri collection does not allow for a complete reconstruction of the original. Nevertheless, the available documentation assists in identifying the main corpus and sheds new light on the aporia contemporary art had in relation to the Italian political context in the years between the two wars. This was a period characterized by a complex machinery in which collectors, artists, critics, and art dealers participated as protagonists of the cultural system – through their aesthetic ideologies, exhibitions, and art market speculations – and politics also played a significant role – looking for consensus among intellectual elites as well as the general populace. With these dynamics in mind, the Valdameri collection should be historically read as resulting from private patronage, and also as exemplifying the propagandization of Italian contemporary art carried out by the regime and its apparatus. In an open letter to Mussolini published in 1929 in the magazine Pegaso, Ojetti stated: “[A] peculiar Fascist style in art will arise only when Italian consciousness and civilization will grow from Fascism; it won’t be realize by people’s wills but by costumes, sentiments, and instinct.”90 In the 1930s, Italian contemporary art was called upon by the state to contribute a style representative of politics, social, and economic ideals, and to act as a model of high “spirit,” civilization, and Fascist revolution.91 The regime’s cultural strategy intended to create a sort of cohesion between aesthetic values, on the one hand, ethics and politics, on the other, yielded a peculiar ambiguity in which different artistic languages coexisted. Symptomatically, this ambiguity is evident in the Valdameri collection’s identity, as shaped by the lawyer himself in the firm belief that only the reconsideration of national tradition made it possible to achieve a modern Italian art aesthetically and ethically representative of the contemporary context, able to outdo the international modernisms and avant-gardes, through a modern language that had its instrinsecal values not in pictorial forms but in moral and social ones.92

Bibliography

Affron, Matthew, and Mark Antliff, eds. Fascist Visions: Art and Ideology in France and Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Anni creativi al “Milione”. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 1980. Exhibition catalogue.

Appella, Giuseppe, ed. Il carteggio Belli-Feroldi 1933–1942. Milan: Skira, 2003.

Armellini, Guido. “Fascismo e pittura italiana. Il primo dopoguerra, metafisica e Valori Plastici.” Paragone, no. 23 (1972): 36–51.

Baldacci, Paolo. De Chirico 1988–1919. La Metafisica. Milan: Leonardo Arte, 1997.

Baldacci, Paolo, and Roos, Gerd. Giorgio de Chirico. Piazza d’Italia (Souvenir d’Italie II) 1913 (July–August 1933). Milan: Scalpendi, 2013.

Barocchi, Paola. Storia moderna dell’arte in Italia. III.1. Manifesti, polemiche, documenti. Dal novecento ai dibattiti sulla figura e sul monumentale, 1925–1952. Turin: Einaudi, 1990.

Beccaria Rolfi, Lidia, and Anna Maria Buzzone. Le donne di Ravensbrück. Testimonianze di deportate politiche italiane. Turin: Einaudi, 1978.

Bertolino, Giorgina, and Poli, Francesco. Felice Casorati. Catalogo generale. I dipinti (1904–1963), vol. 2. Turin: Allemandi, 1995.

Bollettino della galleria del Milione, no. 61 (1939).

Bossaglia, Rossana. Il Novecento italiano. Storia, documenti, iconografia. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1979.

Bottai, Giuseppe. “Fronte dell’arte.” Le Arti 3, no. 3 (1941): 153–58.

Bottai, Giuseppe. “Il Regime per l’Arte.” Corriere della Sera, January 24, 1940.

Bottai, Giuseppe. “La legge sulle arti figurative.” Le Arti 4, no. 4 (1942): 243–49.

Brandi, Cesare. “De Chirico metafisico al Milione.” Le Arti 2, no. 2 (1939–1940): 118–21.

Braun, Emily. “Speaking Volumes: Giorgio Morandi’s Still Lifes and the Cultural Politics of Strapaese.” “Fascism and Culture.” Special issue, Modernism/Modernity 2, no. 3 (September 1995): 89–115.

Braun, Emily, ed. De Chirico and America. Allemandi: Turin, 1996.

Braun, Emily. Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Calzini, Raffaele. “Belle Arti.” L’Illustrazione Italiana, November 26, 1922.

Calzini, Raffaele. “Il plutarco delle rotative.” Corriere della Sera, December 15, 1948.

Calzini, Raffaele. “La XVI Biennale di Venezia.” Emporium 67, no. 401 (1928): 259–80.

Cantatore, Domenico. “Il mercato artistico a Milano: Barbaroux.” Domus, no. 131 (November 1938): 40.

Caputo, Caterina. “Ricerche d’archivio: tre cartoline inedite di Giorgio de Chirico a Douglas Cooper.” Studi OnLine, nos. 5–6 (2016): 11–16.

Carrà, Carlo. “La Raccolta Benzoni.” L’Ambrosiano, December 14, 1926.

Carrà, Massimo. Carrà. Tutta l’opera pittorica. Vol. 1. Milano: Edizioni l’Annunciata e La Conchiglia, 1967.

Cavalli, Gian Carlo. “Galleria di Roma: Mostra della Collezione Valdameri.” Emporium 95, no. 569 (1942): 218–22.

Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde. Edited by Rebecca A. Rabinow, Douglas W. Druick, and Maryline Assante di Panzillo. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. Exhibition catalogue.

Chierici, Giorgia. “Giorgio de Chirico e Venezia – parte III (1937–1947).” Metafisica, no. 19 (2019): 281–92.

Colombo, Nicoletta. “Il sistema dell’arte a Milano 1930–40. Pubblico e privato.” In Milano anni trenta. L’arte e la città. Edited by Elena Pontiggia and Nicoletta Colombo, 39–65. Milan: Mazzotta, 2004. Exhibition catalogue.

Colombo, Nicoletta. “Le gallerie private milanesi protagoniste della storia di ‘Novecento’ (1920–1932).” In Il “Novecento” milanese. Da Sironi ad Arturo Martini, 45–54. Milan: Mazzotta, 2003. Exhibition catalogue.

Cortellessa, Andrea, ed. Giorgio de Chirico, Scritti/1, (1911–1945), Romanzi e scritti critici e teorici. Milan: Bompiani, 2008.

Crespi, Attilio. “La Collezione Valdameri alla galleria di Roma.” Emporium 96, no. 571 (1942): 281–287.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Gaetano Previati,” Il convegno 1, no. 7 (1920): 29–36.

De Chirico, Giorgio. Memorie della mia vita. Milano: La nave di Teseo, 2019. Originally published in 1945.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna. “1920: Ojetti, ‘Dedalo’ e l’arte contemporanea.” Ricerche di storia dell’arte, no. 67 (1999): 5–22.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna. Ugo Ojetti critico d’arte. Dal “Marzocco a “Dedalo.” Florence: Le Lettere, 2004.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna. “Ugo Ojetti e il Marzocco (1896–1899).” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia, no. 4 (1992): 1073–109.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna, ed. Da Fattori a Casorati: capolavori della collezione Ojetti. Viareggio: Centro Matteucci, 2010. Exhibition catalogue.

De Micheli, Mario, Claudia Gian Ferrari, and Giovanni Comisso, eds. Le lettere di Arturo Martini. Milan: Charta, 1992.

De Pisis, Filippo. “La cosiddetta Arte Metafisica.” Emporium 88, no. 527 (1938): 258.

De Sabbata, Massimo. Tra Diplomazia e Arte: le Biennali di Antonio Maraini. 1928–1942. Udine: Forum, 2006.

De Sabbata, Massimo. Mostre d’arte a Milano negli anni Venti. Dalle origini del Novecento alle prime mostre sindacali (1920-1929). Torino: Allemandi, 2012.

Del Puppo, Alessandro. “Da Soffici a Bottai. Una introduzione alla politica fascista delle arti in Italia.” Revista de Història da Arte e Arqueologia, no. 2 (1995–96): 191–204.

Divina commedia. Le visioni di Doré, Scaramuzza, Nattini. Parma: Fondazione Magnani Rocca and Silvana Editoriale, 2012. Exhibition catalogue.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio. “De Chirico al tempo di ‘Valori Plastici.’ Note iconografiche e documenti inediti.” In Studi di storia dell’arte in onore di Federico Zeri, 920–23. Milan: Electa, 1984.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio. Giorgio de Chirico. Gli anni Trenta. Milan: Skira, 1995.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio, and Elena Gigli. “Dove va l’arte moderna? Mostra documentaria su Mario Broglio e Valori Plastici.” In XIII Quadriennale: Valori Plastici. Edited by Paolo Fossati, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani, 275–302. Rome: Palazzo delle Esposizioni; Milan: Skira, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Un contratto inedito tra Giorgio Morandi e Mario Broglio: identificazioni delle opere, storia collezionistica e novità cronologiche del Morandi metafisico e postmetafisico.” Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte, no. 26 (2002): 459–515.

Fossati, Paolo. “Le stanze del collezionista. Appunti sugli inizi delle raccolte d’arte contemporanea in Italia.” In Collezione privata. Arte italiana del XX secolo. Edited by Maria Rodeschini Galati and Francesco Rossi, 19–30. Bergamo: Mazzotta, 1991.

Fossati, Paolo. Valori Plastici: 1918–1922. Torino: Einaudi, 1981.

Gallerie milanesi tra le due Guerre. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2016. Exhibition catalogue.

Garberi, Mercedes. “Morandi e Milano.” In Morandi e Milano. Edited by Stefano Zuffi, 20–33. Milan: Palazzo Reale and Electa, 1990. Exhibition Catalogue.

Gentile, Emilio. The Origin of Fascist Ideology, 1918–1925. New York: Enigma Books, 2005.

Giacon, Danka. “Cortina 1941. La Mostra delle Collezioni d’Arte Contemporanea,” L’Uomo Nero 2, no. 3 (2005): 51–68.

Gotta, Salvatore. L’Almanacco di Gotta. Milan: Mondadori, 1958.

Gotta, Salvatore. “La villa degli artisti.” Corriere della Sera, February 4, 1952.

Gotta, Salvatore. “L’eleganza al lavatoio.” Corriere della Sera, April 10, 1968.

Gotta, Salvatore. “Se non ci fosse stata lei Portofino non esisterebbe più.” Corriere della Sera, May 18, 1949.

Griffin, Roger. The Nature of Fascism. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991.

Gruetzner Robins, Anna. “Marketing Post-Impressionism: Roger Fry’s Commercial Exhibitions.” In The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939. Edited by Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, 85–97. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011.

Hewitt, Andrew. Fascist Modernism: Aesthetics, Politics, and the Avant-garde. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Watercolours and Sculpture II. Christie’s London, December 3, 1996, lot 214. Auction catalogue.

Impressionist and Modern Art and Picasso Ceramics. Christie’s London, February 5, 2016, lot 83. Auction catalogue.

Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale. Christie’s London, June 28, 2017, lot 401. Auction catalogue.

L.P. “Cronache milanesi. Vendita all’asta di raccolta artistiche.” Emporium 63, no. 378 (1926): 403–04.

“La morte di Rino Valdameri.” Corriere della Sera, May 29, 1943.

“La Mostra delle ‘Immagini Dantesche’ inaugurata al Castello.” Corriere della Sera, March 21, 1929.

Lacagnina, Davide. “Arte moderna italiana: collezionismo e storiografia fra le pagine di ‘Emporium’ (1938–1943).” In Emporium II: parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964. Edited by Giorgio Bacci and Miriam Fileti Mazza, 453–78. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2014.

Le opere di Gaetano Previati dell’associazione nazionale fra mutilati ed invalidi di guerra. Milan and Rome: Casa Editrice d’Arte Bestetti e Tumminelli, 1927. Exhibition catalogue.

LI–LII Mostra della Galleria di Roma con opere della Collezione dell’avv. R. Valdameri. Rome: Galleria di Roma; Milan: Officine grafiche, 1942. Exhibition catalogue.

Longhi, Roberto. Carlo Carrà. Milan: Hoepli, 1937.

Longhi, Roberto. “Note d’arte. Al Dio ortopedico.” Il Tempo, February 22, 1919.

Lyttelton, Adrian, ed. Liberal and Fascist Italy, 1900–1945. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Madesani, Angela. Le intelligenze dell’arte. Gallerie e galleristi a Milano 1876–1950. Busto Arsizio: Nomos, 2016.

Marazzi, Martino. “Amelia: The Fate of a Signora from Fascism to Ravensbrück.” The Carolina Quarterly 65, no. 3 (2016): 94.

Margozzi, Mariastella. “L’Azione per l’Arte Contemporanea. Le esposizioni, i premi, le leggi per la promozione e il coordinamento dell’attività artistica.” In Istituzioni e politiche culturali in Italia negli anni Trenta. Edited by Vincenzo Cazzato, vol. 2, 27–106. Rome: Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 2001.

Miraglio, Elena. “Seicento, Settecento, Ottocento e via dicendo: Ojetti e l’arte figurativa italiana.” Studi di Memofonte, no. 6 (2011): 63–79.

Mostra delle Collezioni d’Arte Contemporanea, Cortina d’Ampezzo: Cooperativa anonima poligrafica, n.d. [1941]. Exhibition catalogue.

Negri, Antonello, ed. The Thirties: The Arts in Italy Beyond the Fascism. Florence: Palazzo Strozzi and Giunti, 2012. Exhibition catalogue.

Ojetti, Ugo. “A sua eccellenza Benito Mussolini.” Pegaso. Rassegna di Lettere e Arti 1, no. 1 (1929): 89.

Ojetti, Ugo. “Lo scultore Antonio Maraini.” Dedalo 1, no. 3 (1921): 743–58.

Ojetti, Ugo. Ritratti di artisti. Milano: Fratelli Treves, 1923.

Pacchioni, Anna. “La raccolta Feroldi esposta nelle sale di Brera.” Emporium, no. 97 (1943): 36–38.

Pagé, Suzanne, ed. Années 30 en Europe. Le temps menaçant 1929–1939. Paris: Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris and Flammarion, 1997. Exhibition catalogue.

Pansera, Anty. Storia e cronaca della Triennale. Milan: Longanesi, 1978.

Paul Durand-Ruel, Le pari de l’impressionnisme. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux and Grand Palais, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Picozza, Paolo. “Origine e persistenza di un tòpos su de Chirico.” Metafisica, nos. 1–2, (2002): 326–33.

Piovene, Guido. Le grandi raccolte d’arte contemporanea. La raccolta Feroldi. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1942.

Pontiggia, Elena. “De Chirico-Barbaroux: un carteggio (1930–1954).” Metafisica, no. 19 (2019): 125–63.

Pontiggia, Elena, ed. Il Milione e l’astrattismo, 1932–1938. La galleria, Licini, i suoi amici. Fermo: Palazzo dei Priori; Milan: Electa, 1988. Exhibition catalogue.

Pontiggia, Elena, ed. Il Novecento italiano. Milan: Abscondita, 2003.

Pontiggia, Elena, ed. Massimo Bontempelli. Realismo magico e altri scritti sull’arte. Milan: Abscondita, 2006.

Quarante ans d’Art Italien du futurisme à nos jours. Lausanne: Musée Central des Beaux Arts Lausanne, 1947. Exhibition catalogue.

Ragghianti, Carlo Ludovico, ed. Arte moderna in Italia 1915–1935. Florence: Palazzo Strozzi and Marchi e Bertolli Editore, 1967. Exhibition catalogue.

Rasario, Giovanna. “Le opere di Giorgio de Chirico nella collezione Castelfranco. L’Affaire delle Muse Inquietanti.” Metafisica, nos. 5–6 (2006): 221–303.

R.G., “Come nasce una Galleria d’Arte Moderna. Intervista con Rino Valdameri.” Quadrivio, March 1, 1942.

Robinson, Katherine. “Epistolario Giorgio de Chirico – Jacques Seligmann & Co. Milano – Parigi – New York, 1938. Una mostra mancata.” Metafisica, nos. 9–10 (2010): 118–37.

Robinson, Katherine. “Epistolario Giorgio de Chirico – Julien Levy. Artista e gallerista. Esperienza condivisa.” Metafisica, nos. 7–8 (2008): 293–325.

Roos, Gerd. Giorgio de Chirico e Germain Seligmann. Manovre sul mercato americano tra 1937 e 1938. Milan: Scalpendi, 2012.

Rota, Tiziana. La Galleria Gian Ferrari, 1936–1996. Milan: Charta, 1995.

Rusconi, Paolo. “‘… Una Galleria sulla vetta!’ Cenni sul mercato dell’arte a Milano intorno al 1930.” In Gli anni trenta a Milano. Tra architetture, immagini e opere d’arte. Edited by Silvia Bignami and Paolo Rusconi, 87–102. Milan: Mimesis, 2014.

Rusconi, Paolo. “Via Brera n. 16. La galleria di Pietro Maria Bardi.” In Modernidade Latina. Os Italianos e os Centros do Modernismo Latino-americano. Edited by Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, Luciano Migliaccio, and Paolo Rusconi, n.p. São Paulo: MAC USP, 2014.

Salvagnini, Sileno. Il sistema delle arti in Italia (1919–1943). Bologna: Minerva, 2011.

Salvagnini, Sileno. “L’Ufficio per l’Arte Contemporanea e la politica artistica di Bottai nei fondi dell’ACS.” In Paolo Fossati. La passione del critico. Scritti scelti sulle arti e la cultura del Novecento. Edited by Gianni Contessi and Miriam Panzeri, 293–315. Milan: Mondadori, 2009.

Sansone, Luigi, ed. Gallerie milanesi tra le due Guerre. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2016. Exhibition catalogue.

Schumacher, Thomas L. Terragni e il Danteum. Rome: Officina Edizioni, 1983.

Somaré, Enrico. Storie dei pittori italiani dell’Ottocento. Milano: Edizioni d’arte moderna L’Esame, 1928.

Spackman, Barbara, and Jeffrey T. Schnapp. “Fascism and Culture.” Stanford Italian Review 8, nos. 1–2 (1988): 35–52.

Stone, Maria. The Patron State: Culture and Politics in Fascist Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Storchi, Simona. “Latinità, modernità e fascismo nei dibattiti artistici degli anni Venti.” Cahiers de la Méditerranée, no. 95, (2017): 71–83.

Tarquini, Alessandra. Storia della cultura fascista. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2010.

Vivarelli, Pia. “Classicisme et arts plastiques en Italie entre les deux guerres.” In Les Realismes, 1919–1939. Edited by Pontus Hulten. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980, 66–72. Exhibition catalogue.

Vivarelli, Pia. “La politica di Bottai a sostegno delle collezioni di arte contemporanea e delle gallerie private.” In Gli anni del Premio Bergamo. Arte in Italia intorno agli anni Trenta, 57–64. Bergamo: Galleria d’arte moderna e contemporanea and Electa, 1993. Exhibition catalogue.

XVI Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Venezia: Ferrari, 1928. Exhibition catalogue.

Zagarrio, Vito. “Il fascismo e la politica delle arti.” Studi storici 17, no. 2 (1976): 235–56.

How to cite

Caterina Caputo, “Shaping an Identity for Italian Contemporary Art During the Interwar Period: Rino Valdameri’s Collection,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- Salvator Gotta, L’Almanacco di Gotta (Milan: Mondadori, 1958), 152–53. All translations unless otherwise specified are the author’s. My heartfelt thanks go to the staff of the archives who made their materials available to me for this research, and to Stefano Menichini for forwarding some of these documents. The research is the result of a fellowship awarded in 2019 by the Center for Italian Modern Art in New York. The author is at the disposal of the rightholders to remedy any unintentional copyright omissions relating to the photo credits reproduced.

- Salvator Gotta was a Piedmontese writer and contributor to the magazine Il Marzocco and the newspaper Corriere della Sera. In 1929, he co-founded the Associazione Amici di Portofino, in the town where he met and spent time with Rino Valdameri. L’Almanacco di Gotta is a volume of his memoirs, to date the only identified source that contains a description of Valdameri.

- Rino Valdameri’s curriculum vitae, in Archivio di Stato, Rome, folder: “Ministero dell’Interno, Direzione Generale Pubblica Sicurezza, Divisione polizia politica, fascicoli personali (1926–1944), b. 1397 f. Valdameri avv.”

- Gotta, L’Almanacco di Gotta, 189.

- The need to conduct a more in-depth study of Valdameri and his collection was expressed in 1990 by Mercedes Garberi: “As regards Rino Valdameri, probably of Cremasque origin, lawyer, the news is scarce. Yet his collection was of such a level and interest as to arouse curiosity and deserve further in-depth analyses.” Mercedes Garberi, “Morandi e Milano,” in Morandi e Milano (Milan: Palazzo Reale and Electa, 1990), 21.

- Valdameri’s biographical data is mainly taken from his curriculum vitae, kept in the State Archives of Rome. See note 3.

- Valdameri worked with Nattini on the edition of the Divine Comedy for over a decade. It was published in Milan by Officine dell’Istituto Nazionale Dantesco: the first cantica, “Inferno,” was published between 1921 and 1928; the second, “Purgatorio,” between 1929 to 1936; and the last, “Paradiso,” between 1937 to 1941. Nattini’s original watercolors were recently shown in Italy in the exhibition Divina commedia. Le visioni di Doré, Scaramuzza, Nattini (Parma: Fondazione Magnani Rocca and Silvana Editoriale; Ravenna: MAR Museo d’arte della Città di Ravenna, 2012).

- R.G., “Come nasce una Galleria d’Arte Moderna. Intervista con Rino Valdameri,” Quadrivio, March 1, 1942.

- Valdameri’s curriculum vitae, see note 3.

- “La Mostra delle ‘Immagini Dantesche’ inaugurata al Castello,” Corriere della Sera, March 21, 1929.

- The exhibition was inaugurated in Rome at the House of Dante; it traveled to many Italian cities and made a last stop at the Jeu de Paume in Paris in 1931. Immediately after the Risorgimento and throughout the twenty years of Fascism, a real cult was created around the figure of Dante, considered the initiator of Italian culture. In the 1930s, Valdameri planned to flow the artworks of the Divine Comedy created by Nattini into a special building in Rome called Danteum, based on an architectural project by Giuseppe Terragni and Pietro Lingeri. Valdameri’s project represented a sort of proclamation of Fascism’s myths and cultural ideologies; it was approved by Mussolini, but due to the pressures of war it never came to life. See Thomas L. Schumacher, Terragni e il Danteum (Rome: Officina Edizioni, 1983), 21.

- On literature’s role in Fascist political culture, see Adrian Lyttelton, ed., Liberal and Fascist Italy, 1900–1945 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 216–32. Valdameri’s interest in the political ladder is confirmed in a document dated June 8, 1942, states that Valdameri, having not been able to get the title of Senator (Laticlavio) due to an age limit, hoped to obtain the title of Count. See Segreteria particolare del duce, carteggio ordinario, f. 509374, “Valdameri avv. Rino,” Archivio di Stato, Rome.

- Liceo Artistico and Reale Scuola Superiore degli Artefici were two high schools specializing in the arts.

- The Opera Pia Lombarda Croci was one of the Fascist associations of culture and propaganda founded to financially support the higher education of young people from Milan and the surrounding area.

- On the Milan Triennale, see Anty Pansera, Storia e cronaca della Triennale (Milan: Longanesi, 1978), 34–59 and 245–334.

- On Ugo Ojetti, see Giovanna De Lorenzi, Ugo Ojetti critico d’arte: dal “Marzocco a “Dedalo” (Florence: Le Lettere, 2004).

- Valdameri purchased the villa in Portofino in 1925 c.

- Salvator Gotta, “L’eleganza al lavatoio,” Corriere della Sera, April 10, 1968. The “illustrious personalities” cited in the article include the writers Luigi Pirandello, Massimo Bontempelli, and Sem Benelli; the artists Giorgio de Chirico, Filippo De Pisis, Carlo Carrà, Arturo Tosi, Marino Marini, Francesco Messina, and Arrigo Minerbi; the journalists Luigi Barzini, Giulio de Benedetti, Guido Piovene, and Gino Rocca; the actors Marta Abba, Laura Adani, Luigi Cimara; the musicians Umberto Giordano, Adriano Lualdi, and Ildebrando Pizzetti. Gotta also dedicated another article to Villa Valdameri in Portofino, see his “La villa degli artisti,” Corriere della Sera, February 4, 1952.

- See Giovanna De Lorenzi, “1920: Ojetti, ‘Dedalo’ e l’arte contemporanea,” Ricerche di storia dell’arte, no. 67 (1999): 5–22.

- See De Lorenzi, “Ugo Ojetti e il Marzocco (1896–1899),” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia, no. 4 (1992): 1108–1109.

- Ugo Ojetti, “Lo scultore Antonio Maraini,” Dedalo 3, (1921): 753–54.

- See Margherita Sarfatti, Segni, colori e luci. Note d’arte, (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1925). The first contact between Valdameri and Margherita Sarfatti dates back to 1922, when the lawyer asked several Italian critics and intellectuals (including Sarfatti) for a short text on his editorial work involving Dante. See Valdameri’s letter to Sarfatti, February 14, 1922 (Fondo Sarfatti, Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto).

- On the Valori Plastici group, see Paolo Fossati, Valori Plastici: 1918–22, (Torino: Einaudi, 1981). For more on the Novecento Italiano group, see Rossana Bossaglia, Il Novecento italiano. Storia, documenti, iconografia (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1979); and Elena Pontiggia, ed., Il Novecento italiano, (Milan: Abscondita, 2003).

- For some of the earliest reflections on Italian collecting in the years between the two wars, see Paolo Fossati, “Le stanze del collezionista. Appunti sugli inizi delle raccolte d’arte contemporanea in Italia,” in Collezione privata. Arte italiana del XX secolo, ed. Maria Rodeschini Galati and Francesco Rossi (Bergamo: Mazzotta, 1991), 19–30; on the historical background, see Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, ed., Arte moderna in Italia, 1915–1935 (Florence: Palazzo Strozzi and Marchi e Bertolli Editore, 1967); Paola Barocchi, Storia moderna dell’arte in Italia. III.1. Manifesti, polemiche, documenti. Dal novecento ai dibattiti sulla figura e sul monumentale, 1925–1952 (Turin: Einaudi, 1990); Suzanne Pagé, ed., Années 30 en Europe. Le temps menaçant 1929–1939 (Paris: Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris and Flammarion, 1997); and Antonello Negri, ed., The Thirties: The Arts in Italy Beyond the Fascism, (Florence: Palazzo Strozzi and Giunti, 2012).

- Come nasce una Galleria, 3.

- On Ojetti’s collection see Giovanna De Lorenzi, ed., Da Fattori a Casorati. Capolavori della collezione Ojetti (Viareggio: Centro Matteucci, 2010). Ojetti included Previati in his volume Ritratti di artisti, (Milano: Fratelli Treves, 1923).

- See Giorgio De Chirico, “Gaetano Previati,” Il convegno 1, no. 7 (1920): 29–36; now in Giorgio de Chirico, Scritti/1, (1911–1945), Romanzi e scritti critici e teorici, ed. Andrea Cortellessa, (Milan: Bompiani, 2008), 368–74.

- In the 1920s, Previati was one of the most in-demand painters in auctions in Italy. For instance, at the Giuseppe Chierichetti Collection auction at the Pesaro Gallery in Milan in May 1926, Previati’s paintings were sold at very high prices; in fact, the canvas Il Re Sole was the most expensive sale at the auction (sold at 200,000 Lire). See L.P., “Cronache milanesi. Vendita all’asta di raccolta artistiche,” Emporium 63, no. 378 (1926): 403–04. For additional auctions with Previati’s works of art see Raffaele Calzini, “Belle Arti,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, November 26, 1922, p. 631; and Carlo Carrà, “La Raccolta Benzoni,” L’Ambrosiano, December 14, 1926, p. 3.

- See Le opere di Gaetano Previati dell’associazione nazionale fra mutilati ed invalidi di guerra (Milan and Rome: Casa Editrice d’Arte Bestetti e Tumminelli, 1927). The catalogue’s introductory text was by Sarfatti.

- The use of auctions to place works of art on the market, especially nineteenth-century works, characterized not only Lino Pesaro’s gallery but also many other exhibition spaces in Milan in the 1920s. See Sileno Salvagnini, Il sistema delle arti in Italia (1919–1943) (Bologna: Minerva, 2011), 129–72; and Massimo De Sabbata, Mostre d’arte a Milano negli anni Venti. Dalle origini del Novecento alle prime mostre sindacali (1920–1929), (Torino: Allemandi, 2012), 57–60. For the Pesaro Gallery, see also Nicoletta Colombo, “Le gallerie private milanesi protagoniste della storia di “Novecento” (1920–1932),” in Il “Novecento” milanese. Da Sironi ad Arturo Martini (Milan: Spazio Oberdan and Mazzotta, 2003), 45–54; and Gallerie milanesi tra le due Guerre, ed. Luigi Sansone (Milan: Fondazione Stelline and Silvana Editoriale, 2016), 59–66.

- On the presence of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works in the European art market, see Rebecca A. Rabinow, Douglas W. Druick, and Maryline Assante di Panzillo, eds., Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006); Paul Durand-Ruel, Le pari de l’impressionnisme (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux and Grand Palais, 2014); Anna Gruetzner Robins, “Marketing Post-Impressionism: Roger Fry’s Commercial Exhibitions,” in The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939, ed. Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 85–97.

- See Ugo Ojetti, La pittura italiana dell’Ottocento, (Milano: Casa Editrice d’Arte Bestetti e Tumminelli, 1929); and Enrico Somaré, Storie dei pittori italiani dell’Ottocento, (Milano: Edizioni d’arte moderna L’Esame, 1928).

- Regarding Dedalo, see De Lorenzi, Ugo Ojetti critico d’arte; on Emporium, see Davide Lacagnina, “Arte moderna italiana. Collezionismo e storiografia fra le pagine di ‘Emporium’ (1938–1943),” in Emporium II. Parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964, ed. Giorgio Bacci and Miriam Fileti Mazza (Pisa: Edizione della Normale, 2014), 453–78.

- About two hundred paintings were on display in the exhibition, by artists including: Tranquillo Cremona, Giovanni Fattori, Emilio Gola, Silvestro Lega, Domenico Morelli, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Gaetano Previati, Daniele Ranzoni, Giovanni Segantini, Telemaco Signorini, and many others. See XVI Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte (Venice: Ferrari, 1928).

- Raffaele Calzini, “La XVI Biennale di Venezia,” Emporium 67, no. 401 (1928): 271.

- For an overview of the Valdameri collection, see LI–LII Mostra della Galleria di Roma con opere della Collezione dell’avv. R. Valdameri (Rome: Galleria di Roma; Milan: Officine Grafiche, 1942).

- Come nasce una Galleria, 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Valdameri’s statement is quoted in Pietro Feroldi’s letter to Carlo Belli, June 10, 1939, in Il carteggio Belli-Feroldi 1933–1942, ed. Giuseppe Appella (Milan: Skira, 2003), 175. Feroldi was a Brescian lawyer who, in the 1930s, built up a prestigious collection of contemporary art. On the Feroldi collection, see Guido Piovene, Le grandi raccolte d’arte contemporanea. La raccolta Feroldi (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1942); and Anna Pacchioni, “La raccolta Feroldi esposta nelle sale di Brera,” Emporium 97, no. 577, (1943): 36–38.

- In 1932 Valdameri attempted to modify Nattini’s contract by adopting duping stratagems in order to become the only copyright holder of Nattini’s Divine Comedy artworks. This obscure affair ended in 1933 with a legal dispute in defense of the painter. The document that narrates the whole story in detail is filed in Milan at the Historical Archives of the Banca Commerciale Italiana, Fondo CM, folder. 211, file 9 Nattini.

- Come nasce una Galleria, 3.

- On Fascist political culture and the controversial role played by art in this context, see Guido Armellini, “Fascismo e pittura italiana,” Paragone, no. 23 (1972): 36–68; Vito Zagarrio, “Il fascismo e la politica delle arti,” Studi storici 17, no. 2 (1976): 235–56; Barbara Spackman and Jeffrey T. Schnapp, “Fascism and Culture,” Stanford Italian Review 8, nos. 1–2 (1988): 35–52; Andrew Hewitt, Fascist Modernism: Aesthetics, Politics, and the Avant-garde (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993); Alessandro Del Puppo, “Da Soffici a Bottai. Una introduzione alla politica fascista delle arti in Italia,” Revista de Història da Arte e Arqueologia, no. 2 (1995–96): 191–204; Matthew Affron and Mark Antliff, eds., Fascist Visions: Art and Ideology in France and Italy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); Maria Stone, The Patron State: Culture and Politics in Fascist Italy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998); Emily Braun, Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics Under Fascism (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2000); and Lyttelton, Liberal and Fascist Italy.

- Vittorio Emanuele Barbaroux had opened a gallery in Via Croce Rossa in Milan at the end of the 1920s, together with his father-in-law, Senator Gaspare Gussoni. The gallery, initially called the Esame, was soon transformed into the Milano Gallery; right from the start, it distinguished itself as the exhibition venue of the Novecento group and the “Italiens de Paris.” In 1935 the gallery closed, but Barbaroux did not stop his activities as an art dealer; in 1938, he opened a new commercial space, at Via S. Spirito in Milan, active until 1954. For more on Barbaroux and the Milano Gallery, see Nicoletta Colombo, “Il sistema dell’arte a Milano 1930–40. Pubblico e privato,” in Milano anni trenta. L’arte e la città, ed. Elena Pontiggia and N. Colombo (Milan: Spazio Oberdan and Mazzotta, 2004), 39–65; and Angela Madesani, Le intelligenze dell’arte. Gallerie e galleristi a Milano 1876–1950 (Busto Arsizio: Nomos, 2016), 104–16.

- In 1930, the writer and critic Pier Maria Bardi moved to Rome and sold his art gallery, located in Milan – in front of the Brera Pinacoteca – to Peppino Ghiringhelli, who with his brother Gino and critic Edoardo Persico founded Il Milione Gallery. On Pietro Maria Bardi and his gallery, see Paolo Rusconi, “‘… Una Galleria sulla vetta!’ Cenni sul mercato dell’arte a Milano intorno al 1930,” in Gli anni trenta a Milano. Tra architetture, immagini e opere d’arte, ed. Silvia Bignami and Paolo Rusconi (Milan: Mimesis, 2014), 87–102; and Paolo Rusconi, “Via Brera n. 16. La galleria di Pietro Maria Bardi,” in Modernidade Latina. Os Italianos e os Centros do Modernismo Latino-americano, ed. Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, Luciano Migliaccio, and Paolo Rusconi (São Paulo: MAC USP, 2014), n.p. On the Ghiringhellis’ Il Milione Gallery, see Anni creativi al Milione (Prato: Palazzo Novellicci and Silvana Editoriale, 1980); and Elena Pontiggia, ed., Il Milione e l’astrattismo, 1932–1938. La galleria, Licini, i suoi amici (Fermo: Palazzo dei Priori and Electa, 1988).

- See Domenico Cantone, “Il mercato artistico a Milano: Barbaroux,” Domus, no. 131 (November 1938): 40.

- The contract provided a salary for the artist of one thousand lire per month.

- Arturo Martini, letter to Natale Mazzolà, November 1934, in Mario De Micheli, Claudia Gian Ferrari, and Giovanni Comisso, eds., Le lettere di Arturo Martini (Milan: Charta, 1992), 174.

- “I have no intention of reproducing my larger works and the smaller ones only for a maximum of two copies, because excessive reproduction ruins their natural market lifetime;” Martini, letter to Mazzolà, January 10, 1935, in Madesani, Le intelligenze dell’arte, 110. In spite of the misunderstandings between Martini and his merchants, the artist continued to work for Barbaroux until 1947, the year of the sculptor’s death.

- Giorgio de Chirico’s postcard to Julien Levy, dated January 25, 1937, but postmarked 1938 (Archive of the Julien Levy Gallery, Philadelphia). De Chirico incorrectly dated the postcard 1937, an error he often made on correspondence he sent in January.

- On de Chirico and the art market in the interwar period, see Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, Giorgio de Chirico. Gli anni Trenta (Milan: Skira, 1995); Emily Braun, ed., De Chirico and America (Allemandi: Torino, 1996); Katherine Robinson, “Epistolario Giorgio de Chirico – Julien Levy. Artista e gallerista. Esperienza condivisa,” Metafisica, nos. 7–8, (2008): 293–325; Id., “Epistolario Giorgio de Chirico – Jacques Seligmann & Co. Milano – Parigi – New York, 1938. Una mostra mancata,” Metafisica, nos. 9–10 (2010): 118–37; Gerd Roos, Giorgio de Chirico e Germain Seligmann. Manovre sul mercato americano tra 1937 e 1938 (Milan: Scalpendi, 2012); Caterina Caputo, “Ricerche d’archivio: tre cartoline inedite di Giorgio de Chirico a Douglas Cooper,” Studi OnLine, nos. 5–6, (2016): 11–16.

- On the Broglio collection, see Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco and Elena Gigli, “Dove va l’arte moderna? Mostra documentaria su Mario Broglio e Valori Plastici,” in XIII Quadriennale: Valori Plastici, ed. Paolo Fossati, Patrizia Rosazza Ferraris, and Livia Velani (Rome: Palazzo delle Esposizioni; Milan: Skira, 1998), 275–302; and Flavio Fergonzi, “Un contratto inedito tra Giorgio Morandi e Mario Broglio. Identificazioni delle opere, storia collezionistica e novità cronologiche del Morandi metafisico e postmetafisico,” Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte, no. 26 (2002): 459–515.

- Additional Metaphysical paintings and drawings were acquired directly from Broglio by Valdameri in 1940, specifically he bought Carlo Carrà’s Penelope (Penelope, 1917; see Massimo Carrà, Carrà. Tutta l’opera pittorica, vol. 1, Milano: Edizioni l’Annunciata e La Conchiglia, 1967, 319), Il Cavaliere Occidentale (The Western Knight, 1917; see Carrà. Tutta l’opera pittorica, vol. 1, 321), and six unspecified still lifes by Giorgio Morandi. See Valdameri, letter to Broglio, December 6, 1940 (Fondo Valori Plastici, GNAM Archives, Rome).

- See Paolo Baldacci, De Chirico 1988–1919. La Metafisica (Milan: Leonardo Arte, 1997), cat. no. 133, 370. The Trovatore was formerly in the Broglio Collection.

- See Baldacci, De Chirico, cat. no. 132, 368. This work also came from the Broglio collection.

- See Come nasce una Galleria, 3.

- See Bollettino della Galleria Il Milione, no. 61 (1939). The works lent by Valdameri for the exhibition included: I pesci sacri (The Sacred Fish, 1919; Baldacci, De Chirico, cat. no. 147, 407), Il trovatore (Troubadour,1917; Baldacci, De Chirico, cat. no. 133, 370), Interno metafisico dalla ciambella e biscotto (Metaphysical Interior with Biscuit and Matchbox, 1918; Baldacci, De Chirico, cat. no. 140, 395), Interno metafisico con piccola officina (Metaphysical Interior with Small Factory, 1917; Baldacci, De Chirico, cat. no. 130, 366), Il ritorno di Ettore (The Return of Hector), and Il Figliuol Prodigo (The Prodigal Son, 1922; Baldacci, De Chirico, cat. no. A1, 419).

- For additional information about the collaboration between de Chirico and Barbaroux, see Elena Pontiggia, “De Chirico-Barbaroux: un carteggio (1930–1954),” Metafisica, no. 19 (2019): 125–63.

- Pietro Feroldi, letter to Carlo Belli, January 23, 1940, in Il carteggio Belli-Feroldi, 186.

- In Feroldi’s letters to Belli foreign names are often misspelled.

- See Memorie della mia vita (Milan: La nave di Teseo, 2019), 249; originally published in 1945.

- See Paolo Baldacci and Gerd Roos, Giorgio de Chirico. Piazza d’Italia (Souvenir d’Italie II) 1913 (July–August 1933) (Milan: Scalpendi, 2013); and Paolo Picozza, “Origine e persistenza di un tòpos su de Chirico,” Metafisica, nos. 1–2 (2002): 326–33.

- See Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Watercolours and Sculpture II (auction catalogue), Christie’s London, December 3, 1996, lot 214; and Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale (auction catalogue), Christie’s London, June 28, 2017, lot 401.

- Valdameri owned both De Chirico’s metaphysical paintings and post-metaphysical ones. The list of De Chirico’s artworks exhibited at the Galleria di Roma is stored in the GNAM archives in Rome.

- See LI–LII Exhibition at the Gallery of Rome con opere della Collezione dell’avv. R. Valdameri. Bontempelli knew Valdameri since the 1920s, in fact he attended Valdameri’s Villa in Portofino as well as the lawyer’s home in Milan.

- See Roberto Longhi, “Note d’arte. Al Dio ortopedico,” Il Tempo, February 22, 1919.

- See Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, “La Seconda Quadriennale d’Arte Italiana. Giorgio de Chirico,” Critica d’Arte, (October 1935): 54.

- See Cesare Brandi, “De Chirico metafisico al Milione,” Le Arti 2, no. 2 (1939–40): 118–21.

- Gian Carlo Cavalli, “Galleria di Rome: Mostra della Collezione Valdameri,” Emporium 95, no. 469 (1942): 218–22.

- Attilio Crespi, “La Collezione Valdameri alla galleria di Roma,” Emporium 96, no. 571 (1942): 281–87.

- Carlo Belli, draft of letter to Rino Valdameri, February 8, 1942, in Il carteggio Belli-Feroldi, 263.

- Belli, draft of letter to Valdameri, February 8, 1942, (Fondo Belli, Bel.I.154.210a, MART Archives, Rovereto; unpublished).

- Gino Severini, “A proposito dell’esposizione a Roma della Raccolta Valdameri,” February 7, 1942, typewritten transcript (Fondo Severini, Sev.III.3.25, MART Archives, Rovereto).

- On Giuseppe Bottai, see Mariastella Margozzi, “L’Azione per l’Arte Contemporanea. Le esposizioni, I premi, le leggi per la promozione e il coordinamento dell’attività artistica,” in Istituzioni e politiche culturali in Italia negli anni Trenta, ed. Vincenzo Cazzato, vol. 2 (Rome: Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 2001), 27–106. On the Contemporary Art Office, see Pia Vivarelli, “La politica di Bottai a sostegno delle collezioni di arte contemporanea e delle gallerie private,” in Gli anni del Premio Bergamo. Arte in Italia intorno agli anni Trenta (Bergamo: Galleria d’arte moderna e contemporanea and Electa, 1993), 57–64; Sileno Salvagnini, “L’Ufficio per l’Arte Contemporanea e la politica artistica di Bottai nei fondi dell’ACS,” in Paolo Fossati: la passione del critico. Scritti scelti sulle arti e la cultura del Novecento, ed. Gianni Contessi and Miriam Panzeri (Milan: Mondadori, 2009), 293–315.

- Giuseppe Bottai, “Fronte dell’arte,” Le Arti 3, no. 3 (1941): 154.

- See Giuseppe Bottai, “La legge sulle arti figurative,” Le Arti 4, no. 4 (1942): 243–49.

- Giuseppe Bottai, “Il Regime per l’Arte,” Corriere della Sera, January 24, 1940. Emblematically in 1941 Bottai supported the organization of the Cortina d’Ampezzo exhibition-prize for Italian contemporary art collections. The show involved twenty collectors, including Carlo Cardazzo and Alberto Della Ragione, and constitutes a first official recognition of Italian collecting. Due to disagreements and personal rivalry with other competitors, Valdameri did not take part in the exhibition. See Catalogo della Mostra delle Collezioni d’Arte Contemporanea, (Cortina d’Ampezzo, August 10–31, 1941), Cortina d’Ampezzo: Cooperativa anonima poligrafica, n.d. [1941]. For more on the exhibition, see Danka Giacon, “Cortina 1941. La Mostra delle Collezioni d’Arte Contemporanea,” L’Uomo Nero 2, no. 3 (2005): 51–68.

- Valdameri and Bottai were personally in touch from 1938, when the Minister financed Valdameri’s project (already approved by Mussolini in 1935) of building three residential Studios for artists in the Comacina Island, on Lake Como. The architectural plan was designed by Pietro Lingeri under the supervision of the Brera Accademy of Fine Arts, at that time directed by Valdameri.

- Come nasce una Galleria, 3.

- Giuseppe Bottai, “Fronte dell’arte,” Le Arti 3, no. 3 (1941): 156.

- Documents from the Brera Pinacoteca Archive report deposits by Valdemeri but not the list of paintings stored. Transcriptions of the documentation are in Giorgia Chierici, “Giorgio de Chirico e Venezia – parte III (1937–1947),” Metafisica, no. 19 (2019): 281–92.

- When, in November 1942, Valdameri went back to the Sforzesco Castle to deposit Nattini’s Divine Comedy drawings, he did not leave the paintings of his collection.

- See “La morte di Rino Valdameri,” Corriere della Sera, May 29, 1943. A copy of Valdameri’s death certificate is filed in the historical registry of the Milan Council.

- Amelia Valdameri was keen on art and literature, like her husband: she was a member of the Lyceum Club of Milan, a cultural association composed of aristocrats and upper-middle-class women. On Amelia Valdameri, see Raffaele Calzini, “Il plutarco delle rotative,” Corriere della Sera, December 15, 1948; and Salvator Gotta, “Se non ci fosse stata lei Portofino non esisterebbe più,” Corriere della Sera, May 18, 1949.

- Pietro Feroldi, letter to Carlo Cardazzo, June 2, 1943 (Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Istituto di Storia dell’Arte, Fondo Cardazzo, Venice).

- Badoglio was a friend of Amelia and Rino Valdameri, so much that he sponsored their son’s sacramental confirmation in 1937.

- The deportation of Amelia Valdameri to a Nazi concentration camp is mentioned in Lidia Beccaria Rolfi and Anna Maria Buzzone, Le donne di Ravensbrück. Testimonianze di deportate politiche italiane (Turin: Einaudi, 1978), 161. The official Ravensbrück list that mentions her arrival at the concentration camp on October 11, 1944, is published in Martino Marazzi, “Amelia: The Fate of a Signora from Fascism to Ravensbrück,” The Carolina Quarterly 65, no. 3 (2016): 94.

- See Giorgina Bertolino and Francesco Poli, Felice Casorati. Catalogo generale. I dipinti (1904–1963), vol. 2 (Turin: Allemandi, 1995), cat. no. 782. The painting reappeared on the market in a 2016 auction. See Impressionist and Modern Art and Picasso Ceramics (auction catalogue), Christie’s London, February 5, 2016, lot 83.

- The de Chirico works coming from the Valdameri collection included: I pesci sacri (The Sacred Fish, 1919; no. 19), Il figliol prodigo (The Prodigal Son, 1922; no. 20), Il ritorno del figliol prodigo (The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1919; no. 31). See Quarante ans d’Art Italien du futurisme à nos jours (Lausanne: Musée Central des Beaux Arts Lausanne, 1947); the show later traveled to the Kunstmuseum of Lucerne.

- Ugo Ojetti, “A sua eccellenza Benito Mussolini,” Pegaso. Rassegna di Lettere e Arti 1, no. 1 (1929): 89.

- See Marla Stone, “The State as Patron: Making Official Culture in Fascist Italy,” in Fascist Visions, 205–38.

- On the duality of classicism and modernity in the interwar period, see Pia Vivarelli, “Classicisme et arts plastiques en Italie entre les deux guerres,” in Les Realismes, 1919–1939, ed. Pontus Hulten, (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980), 66–72; and Simona Storchi, “Latinità, modernità e fascismo nei dibattiti artistici degli anni Venti,” Cahiers de la Méditerranée, no. 95, (2017): 71–83.