New York 1959: Medardo Rosso at the Peridot Gallery

Chiara Fabi Chiara Fabi Medardo Rosso, Issue 6, December 2021https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/medardo-rosso/

This article explores the circumstances that surrounded the first solo exhibition dedicated to Medardo Rosso in the United States, organized in 1959 by New York’s Peridot Gallery. After surveying the fortune of modern and contemporary Italian art in the US during the early years after World War II, the author illustrates how Rosso’s critical and commercial fortune stemmed from a complex interplay between commercial dealers, galleries, and museum professionals. All of these actors managed to establish Rosso as a forerunner of more recent Italian artists, such as the Futurists.

In December 1959, the Peridot Gallery in New York—a commercial gallery primarily dealing in Abstract Expressionism—presented a small-scale retrospective of the Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso.1Organized by the art dealer Louis Pollack, with the collaboration of Giorgio Nicodemi, former director of the museums of Milan, it was the first solo show dedicated to Medardo Rosso in the United States. My paper will trace the diverse issues this monographic exhibition raised, from an exploration of its genesis to an examination of the cultural and historical conditions that paved the way for Rosso in the United States.

The 1950s marked the start of a renewed, American interest in Italian art and culture. By the end of World War II, as a result of the Marshall Plan (formally the European Recovery Program), the United States had established a paternalistic relationship with Italy. This new alliance was bolstered by the enticing image of Italy that American magazines and tabloids conveyed, advertising the nation as an impoverished, but fascinating destination, resonant with mysterious vestiges of the past.2Cast as a land of natural beauty, enriched by the monuments of antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Baroque period, Italy again became an attraction for Americans. Artists also rediscovered the nineteenth-century tradition of the grand tour, a pilgrimage which had been codified with the institution of the American Academy in Rome in 1911. Even the experience of World War II, which brought US troops throughout Europe, represented a strange parallel to this activity and contributed to its revival.

A report from the Institute of International Education indicated that between the years 1949 and 1956, a large number of the American art students went abroad to Italy: 121 painters and sculptors flocked to the peninsula, while only 83 went to France and just 12 to the United Kingdom.3 No less surprising was the number of American Fulbright artists who traveled to Italy between 1949 and 1956, inspiring a show of their works in 1957 at the Downtown Gallery in New York.4

As a consequence of this reaffirmed predilection for Italy, the number of exhibitions highlighting the interaction between the two countries rapidly increased. Already in 1943 James T. Soby and Dorothy C. Miller organized Romantic Painting in Americaat the Museum of Modern Art, which included American painters who had traveled to and lived in Italy during the nineteenth-century. 5 In 1951 the Detroit Institute of Arts, as a supplement to their Travelers in Arcadia exhibition, showed paintings by contemporary artists who had recently sojourned in Italy.6 In 1955, the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute in Utica organized Italy Rediscovered, devoted to American artists who had gone to Italy since World War II.7 The same spirit of cultural exchange distinguished Twentieth-Century Italian Art8, held in 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art: as explained by Alfred Barr, its purpose was to promote sympathy and understanding between Italy and United States on a cultural level. 9 Italy’s artistic popularity in the US led a journalist of the era to write: “Painters, sculptors, architects, craftsmen fashion and industrial designers, musicians, writers, and those of the theatrical world have turned to Italy in great numbers for new ideas and training. Modern Italian art is being shown in every country of the world today and the Italians themselves are beginning to feel their own strength and capacities.”10

Therefore, when twelve Medardo Rosso sculptures went on view at the Peridot Gallery in 1959, the event was one of many manifestations of this larger American investment in Italy. The choice to focus on Medardo Rosso, an artist almost unknown in the United States, was however unusual. Perhaps because of its apparent anomaly, to date, this exhibition has received scant attention. But a close reading of the circumstances surrounding its inception and reception is revelatory to understanding the establishment of Rosso’s reputation in the United States, as well as the larger framework created by the burgeoning relationship between the Italian and New York art worlds within which this occurred.

Although the wider American public was unfamiliar with Rosso in 1958-1959, art world experts must have been acquainted with him. In 1907, when Rosso was still alive, the influential magazine American Art News introduced him as “a big name among continental connoisseurs who regard him to some extent as the inspirer of Rodin”.11 And in 1915, the New York connoisseur and art collector Charles Louis Borgmeyer, author of The Master Impressionist (1913) and Among Sculptures (1914), also added in the same journal a biting remark regarding Rosso’s non-existent status in the US: “It seems strange that he is practically unknown here as I am told that some fifty of his works can be found in the museums in Paris, Rome, Florence, Milan, Turin, Dresden, […] London. The controversy that has raged from time to time over his connection with Rodin’s Balzac, makes of him an interesting subject outside of his marvelous work”.12 Borgmeyer referred to the presence of three Rosso sculptures in the U.S. at that time: one in Chicago and two in New York. These were probably located in private collections, but the lack of further documentation does not allow me to establish the accuracy of this information. Following these mentions, the 1926 exhibition, Modern Italian Art, organized by the Italian American Society at the Grand Central Galleries in New York, featured four of Rosso’s works: Ecce Puer, The Servant, Man Reading and a Child.13 The show, which traveled to Boston, Washington, and Pittsburgh, earned some acclaim in the US. Indeed, writer Elisabeth Luther Cary dedicated a long paragraph to Rosso, demonstrating a nuanced understanding of his approach to sculpture in her review of the show for The American Magazine of Art: “The sculptor Medardo Rosso, born in the same decade with Boldini and Mancini, makes his impression by the eloquent quietness of his flowing modulation of surface. Whatever the medium, the effect is that of wax that would melt at the touch of a warm hand into a fluid. Comparing his works with that of Gemito, of the same generation, it is seen to belong to the marching spirit that looks forward without obvious reminiscence of the past, however deeply rooted it may be in the racial tradition”.14

More references to Rosso followed between 1929 and 1931. In 1929, right after Rosso’s death and in the same year of his first retrospective at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, another review in The American Magazine of Art referenced his sculptures in the Venice Biennale: “[…] two examples of the genius of Medardo Rosso, whose influence has steadily grown since his death. His profound human and artistic expression emerges more clearly, day by day, from his masses of wax, which, like the mystery of life, always retain, hidden and partly hidden, so much more than man’s most highly developed gifts can call forth.”15 In 1931 he was noticed again in The New York Times on the occasion of his large-scale retrospective installed within the I Quadriennale d’Arte Nazionale of Rome: “Only four deceased artists have been included. Medardo Rosso, probably the best artist in the show, spent most of his life in Paris. In 1929 a retrospective of his sculptures, held in the Salon d’Automne, was highly praised. Nearly all of his drawings are on view here”.16

Rosso’s international rediscovery did not occur through these incidental cases, however, but rather in 1950, when the Venice Biennale (the second one held since the end of World War II) exhibited almost fifty of his works. The show coincided with the publication of Mino Borghi’s famous monograph on Rosso, and was a triumph.17 In an unsigned editorial published in October 1950, The Burlington Magazine proclaimed Rosso “The most distinguished sculptor of the symbolist period in Europe, indeed the only sculptor of international significance if we agree to relegate Rodin to an earlier, more optimistic phase in art. An exhibition of his works in the Italian pavilion at the Biennale this summer has aroused the curiosity and interest of many foreign visitors to Venice, who presumed that the history of Italian sculpture closed with the Neo Classicist Canova”.18 The same year some excellent reproductions of Rosso’s sculptures and drawings were illustrated in the volume Pittura e scultura d’avanguardia in Italia, published by Domus, authored by the journalist Raffaele Carrieri, and translated into English in 1955, which drew public attention to the artist in the US.19

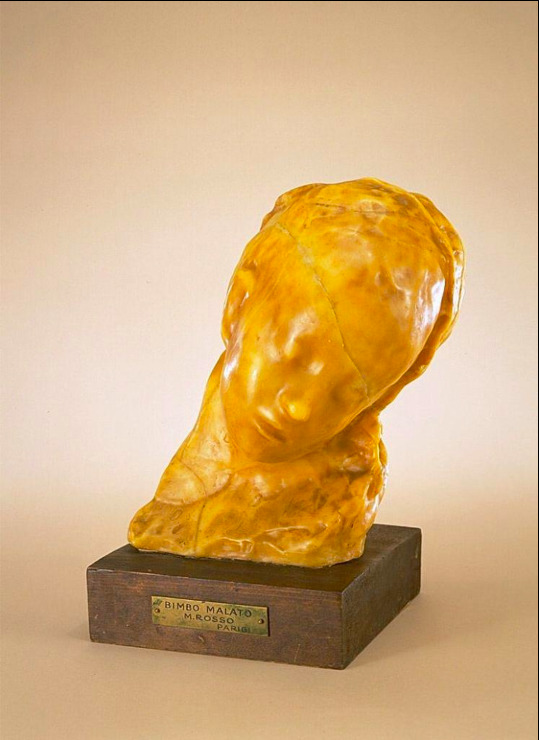

If these were the precedents to Rosso’s introduction in the US, the solo exhibition at the Peridot Gallery was a turning point in the American reception and dissemination of his artwork. The show, which opened in December 1959, displayed twelve sculptures: the painted plaster Lo Scaccino; a series of wax sculptures: The Concierge, The Golden Age, Smiling Girl, Jewish Boy, Bookmaker, Sick Boy (Fig. 1), Head of a Young Woman, and Behold the Child; and three bronze sculptures: Smiling Woman, The Boy in the Sun, and Mask of Smiling Woman.20 The Peridot’s exhibition checklist reveals that Rosso works were entering museum collections at this time. In fact, the Bookmaker and The Concierge boasted MoMA credit lines in the exhibition catalogue.21Among the other public institutions who were listed as lenders to the show was the University of Nebraska. Significantly, their wax Jewish Boy, obtained in 1958, was the first Rosso sculpture ever to enter a public American art collection.22

The Peridot Gallery continued to show Rosso sculptures after the solo presentation. He was included in several group exhibitions between 1960 and 1962. And, in addition to the sales recorded to MoMA and the University of Nebraska, Joseph Hirshhorn bought at least eight bronzes and waxes, which today belong to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC;23 Robert H. Tannahill bought a bronze version of Jewish Boy, today at the Detroit Institute of Arts.24 Lydia Winston Malbin bought, in 1960, a wax version of Ecce Puer; she traveled to New York City and home on the same day just to see this work, which was on exhibit at the Peridot Gallery.25 Since nearly all of the early acquisitions of Rosso sculpture—that is, those from the late 1950s and early 1960s—passed through the Peridot Gallery, this would indicate that they were the primary and the first dealer for Rosso in the US, responsible for selling his works to private and public collections here. Unfortunately, most of the sculptures exhibited at the Peridot Gallery are not in the catalogue raisonné. Giorgio Nicodemi seems to be the one who authenticated a number of these works, as supported by a January 4, 1960 letter from him to Louis Pollack.26

Let us backtrack a moment. What were the specific circumstances surrounding this rather sudden and unexpected spotlight on Rosso in the US with the Peridot show? And why would a gallery primarily devoted to American Abstract Expressionist painters realize an exhibition on the mostly unfamiliar sculptor Medardo Rosso? Several individuals helped to spread Rosso’s reputation in the US, as did the larger phenomena of cultural exchange hinging on the post-war Italy-US axis alluded to previously. In fact, the attention Rosso received in the US was not only tied to the writings and events parsed in the first part of this paper. Rosso’s ingrained modernity also led to a reading of his sculpture that worked inversely, through the accomplishments of more contemporary Italian artists and, especially, sculptors, who were achieving renown in New York in the 1950s.

First of all, it is likely that Robert Goldwater, an art historian and, at the time, Director of the Museum of Primitive Art in New York, played a role in encouraging Peridot’s show. In his 1945 book Artists on Art: From the Fourteenth to the Twentieth Century Goldwater included the first English translation of Rosso’s responses to the early twentieth-century French critic, Edmond Claris, quoted in the latter’s De l’Impressionisme en Sculpture: Auguste Rodin et Medardo Rosso (1902), a book in which Claris exalted Rosso for his use of impressionism in sculpture. Goldwater was also married to the French sculptor Louise Bourgeois, whose works were exhibited several times at the Peridot Gallery. Finally, Goldwater was a good friend of the dealer Louis Pollack, as evidenced by his memorial of Pollack, published in 1970.27

Above all, it is the transcript of the introduction to a lecture given by Margaret Scolari Barr in Toronto in 1975 (today in the Lydia Winston Malbin papers) that can help us better understand the roots of the Peridot show and the American rediscovery of Medardo Rosso. Scolari Barr recounted that the adventurous dealer Louis Pollack, traveling in Italy, “was amazed by Rosso’s work in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome and with persistence managed to track down some examples in private hands which he exhibited in his Peridot Gallery in New York.28 For Alfred Barr – director of the Museum of Modern Art – it was like recognizing an old friend!”. She further explained that Alfred Barr, during a 1928 journey to Italy, had been “greatly struck by several pieces by the Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso” in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna.29 When he saw the artist again at the Peridot show, “he prevailed on his trustees to let him acquire two pieces” (The Concierge and Bookmaker) and “he proposed having a one-man show of his work”.30

Margaret Scolari Barr, the Irish-Italian art historian wife of Alfred Barr, soon became involved in this project. In 1 January 960, after the closure of the Peridot show, she wrote a brief article about Medardo Rosso, published in Art News.31 A few years later, in 1963, at the same time as the large-scale Rosso retrospective organized by the Museum of Modern Art, she published a monograph of him—the first book in English on Rosso.32 In October 1963 Margaret Barr also helped Lydia Winston Malbin buy four additional works by Medardo Rosso: a wax version of Sick Boy (today at the Nasher Sculpture Center of Dallas), a bronze of Man in Hospital, a wax of Jewish Boy and a wax of The Flesh of Others, all sculptures that were purchased in Amsterdam from Miss Osterkamp, representative of the estate of Etha Fles.33 It is clear, therefore, that the American rediscovery of Rosso is tied to the figures of Alfred Barr and Margaret Scolari Barr, in addition to the Peridot Gallery.

If we situate the Peridot show within the Italian contemporary art scene in the United States, and especially in New York, we can glean additional reasons for the emerging interest in Rosso’s work. As already noted, American interest in Italian art and culture was rekindled in the 1950s and came to encompass contemporary art. Consequently, the US-Italy art market was no longer restricted to the Old Masters, but now embraced twentieth-century artists. Among New York’s commercial galleries, the Catherine Viviano Gallery promoted contemporary Italian art, bringing in works by Afro and Mirko Basaldella, Fausto Pirandello, and Renato Birolli. The Buchholz Gallery (then the Curt Valentine Gallery) and the World House Galleries both specialized in Italian art, and among the artists they represented were the major sculptors Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù.34 In this decade contemporary Italian art was securing American followers and entering seminal private and public collections. The richness and depth of this collecting can be seen by the number of works of art that MoMA sent to Italy for the exhibition Italian Art from American Collections. The show, which was mostly made up of loans, comprised more than 150 works (including paintings and sculptures). Among the artists exhibited was Medardo Rosso.35

Within this context, Italian sculpture garnered almost equal attention to Italian painting in a period dominated in the US by the two-dimensional works of the Abstract Expressionists. From 1945-1955 the Museum of Modern Art secured several three-dimensional Italian works. The museum acquired an Arturo Martini (a sculptor who was almost entirely unknown in the US) in 1949, along with a Lucio Fontana ceramic, a Marino Marini bronze, and an Alberto Viani marble.36 In 1956 MoMA bought Manzù’s Potrait of a Lady, cast the year before. Some of these sculptures were exhibited in 1949 in Twentieth-Century Italian Artand, as Barr wrote at the show’s close, they were an enormous success: “(…) Many visitors to the current exhibition have felt that the recent Italian sculptors surpassed the painters. To the purchase of Marino Marini’s haunting bronze Horseman, announced some months ago, the Museum has now added Martini’s Dedalus and Icarus in which fragmentation of the figures has been used with poetic relevance; Fontana’s ceramic crucifix, a brilliant fusion of baroque movement with expressionist fervor; and the young Viani’s grandly modeled marble torso”.37

Of course, Medardo Rosso belonged to a previous generation of Italian sculptors. The innovative nature of his works, however, constituted a precedent for all of the sculptors just discussed. These works, located in the US, by such artists as Manzù, Marini, and Martini indirectly introduced the conceptual and formal issues posed by Rosso’s sculpture. Given this atmosphere, it was certainly not a coincidence that Joseph Hirshhorn, one of Marino Marini’s most committed collectors, obtained many of the Rossos from the Peridot Gallery, because the one artist justified the presence of the other within the context of his collection. It was also not a coincidence that Rosso sculptures entered the Harry and Lydia Winston Collection, if we consider that their famous collection of Futurist artists was assembled primarily during the fifties and that Rosso was an artist beloved by the Futurists, especially by Umberto Boccioni. In 1955 Lydia Winston, thanks to a road trip arranged by the Il Milione Gallery of Milan, had the opportunity to visit the home and the studio of Medardo Rosso in Barzio, escorted by the son of the artist, Francesco, and his wife. Even if no works were purchased on this trip, the journey acquainted them with Medardo Rosso’s sculpture, and perhaps alerted them to the relationship between Rosso and the Futurists.38 Thus, the growing knowledge of and estimation for 20th-century Italian art allowed Medardo Rosso to enter critical discussions, collections, and the commercial market for modern art in the United States.

A letter sent by Mario Vianello Chiodo to Margaret Scolari Barr on June 2, 1960 further illustrates the new horizons of the American art market for Medardo Rosso following the exhibition of the Peridot Gallery.39 Vianello Chiodo, a lawyer and a good friend of Rosso, was the only person the artist had authorized to make casts of the sculptures that he owned. Barr had recently purchased a third Rosso work from Vianello Chiodo for the Museum of Modern Art: a posthumous bronze version of Man Reading. In response to a letter Scolari Barr had written to Vianello Chiodo, telling him how highly the Museum valued the sculpture, Vianello Chiodo felt encouraged to write: “given the success of the Man Reading I feel encouraged to finally cast the five other works I have, […] and I would like to place them well. Now that America has rediscovered Rosso’s sculpture, I think his works can probably affect some museums or some great collectors […]. If Mr. Barr can help me, I’d be happy. I especially need his authoritative advice. I read that the show in New York was organized by a dealer, Mr. Pollack, to whom I could write, but I’d rather avoid dealers and brokers”.40 This letter is very rich: it documents the excitement – if within a small circle – regarding Rosso’s fortunes in mid-century USA and it also exemplifies the complicated relationship between museums, commercial dealers, and galleries at that time (particularly when dealing with modern Italian art)—one that impacted the dissemination of not only real Rossos, but also posthumous Rossos, in the US. This issue had and has its own ramifications. While these are

beyond the parameters of my paper’s focus and my overall areas of research, they certainly are matters that remain to be explored in the future.

Bibliography

“Americans in Italy.” Life (September 15, 1952).

Ashton, Dore. “Art: Year’s Acquisition.” The New York Times. December 04, 1959.

Borghi, Mino. Medardo Rosso. Milan: 1950. “Editorial. Medardo Rosso 1858-1928”. The Burlington Magazine, XCII, no. 571 (October 1950): 277.

Borgmeyer, Charles L. “Rossos not Rodins.” American Art News,13, No. 15 (Jan. 16, 1915): 4.

Carrieri, Raffaele. Avant-Gard Painting and Sculpture in Italy, 1890-1955. Milan: Edizioni della Conchiglia/ Istituto Editoriale Domus, 1955.

Exhibition of Modern Italian Art. Edited by the Italy America Society. New York: 1926. Exhibition Catalogue.

Gerard, Helen. “Radical Changes in the XVIth Venetian Biennial”, The American Magazine of Art no. 20, (February 1929): 82.

Goldwater, Robert. In memoriam. Louis Pollack, 1921-1970 (New York: Peridot Gallery, 1970).

“Italy Gets Dressed Up.” Life (August 1951).

Lombardo, Joseph Vincent. “20th Century Italian Art.” Art Education, V, no. 6, 1 (December 1952).

“London Letter.” American Art News. 5, no. 12 (Jan. 5, 1907): 5.

Luther Cary, Elisabeth. “The Modern Italian Exhibition.,” The American Magazine of Art, 17, no. 4 (April 1926): 176.

Monotti, Francis. “Italian Art. Modern Painting and Sculpture in Rome.” The New York Times. June 21, 1931: 107.

Romantic Painting in America. Edited by J. Thrall Soby and D. Canning Miller. New York: 1943. Exhibition Catalogue.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. “Reviving Medardo Rosso.” Art News 58, no. 9 (January 1960): 38.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. Medardo Rosso. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1963.

“Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition Service.” Report on the National Collection of Fine Arts including the Freer Gallery of Art, 83 (1955).

The First Exhibition in America of Sculpture by Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928, Introduction by Giorgio Nicodemi. Peridot Gallery, December 15, 1958 to January 16, 1959. Exhibition Catalogue.

Travelers in Arcadia; American Artists in Italy. Detroit: 1951. Exhibition Catalogue.

Twentieth-Century Italian Art. Edited by Alfred Barr. New York: 1949. Exhibition Catalogue.

- The First Exhibition in America of Sculpture by Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928, Introduction by Giorgio Nicodemi. Exhibition Catalogue, Peridot Gallery, December 15, 1959 to January 16, 1960. Both the catalogue of the Peridot Gallery exhibition, as well as Paola Mola and Fabio Vitucci’s catalogue raisonné of Rosso list the dates of the show for 1958 and 1959. However, upon further examination, these dates appear to be incorrect, and likely brought about by a typographic mistake, as evidenced by multiple announcements and reviews, including the Gallery Notes on The New York Times, December 20, 1959, XII. See Fancesco Guzzetti’s article in this same issue for more information.

- See, for example: Italy Gets Dressed Up, «Life», august, 1951; “Americans in Italy”, Life, September 15, 1952.

- Report from the Institute of International Education, years 1949-56. James Graham Sons Gallery Records, 1950s-1980s, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- Dunveen-Graham exhibition of Fulbright Artists, September-october 1956. James Graham Sons Gallery Records, 1950s-1980s, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- Romantic Painting in America. Exhibition Catalogue edited by J. Thrall Soby and D. Canning Miller. New York: 1943.

- Travelers in Arcadia; American Artists in Italy. Exhibition Catalogue. Detroit: 1951.

- “Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition Service,” Report on the National Collection of Fine Arts including the Freer Gallery of Art, 83 (1955).

- Twentieth-Century Italian Art. Exhibition Catalogue edited by A. Barr. New York: 1949.

- “The idea of an exhibition of Modern Italian art was proposed to the Trustees as long ago as 1933 after Marga and I had spent several months in Rome. Such a show falls in line with our past exhibitions of German painting and sculpture in 1932 and Mexican art in 1941. We discussed the matter in detail with Cesare Brandi in 1940 but frankly did not want to collaborate with fascist Italians. Mr. Soby has also been much interested in modern Italian art so that two years ago we were much encouraged by your interest and by that shown by the Italian Government authorities. However, as in the past, we plan to organize our exhibition with complete independence of government supervision, although we have occasionally had formal, official approval in order to secure loans from national museums. We realize of course that the present political situation in Italy is delicate and complicated. Although we hope that the exhibition will promote sympathy and understanding between Italy and United States on a cultural level […]”. Alfred Barr, Jr., to Charles Rufus Morey, first Cultural Attaché to the American Embassy in Rome and Acting Director of the American Academy in Rome, April 24, 1948. Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers, The Museum of Modern Art Archives.

- Joseph Vincent Lombardo, “20th Century Italian Art”, Art Education, V, no. 6, 1 (december 1952).

- “London Letter”, American Art News 5, no. 12 (Jan. 5, 1907), 5.

- “[…] In your issue of Jan. 2, I find the following headline over an interesting story, “Venice Gets Rodins”. The error in this headline is obvious. It should have read “Venice Gets Rossos.” The roomful of works by Medardo Rosso, at the International Art Exhibition held at Venice last summer was the real sensation of the exhibition. That onefourth of the entire collection has been acquired by this Galleria d’Arte Moderna of Venice betoken an extraordinary appreciation. I believe there are but three of Ross’s works in the United States, one in Chicago and two in New York. It seems strange that he is practically unknown here as I am told that some fifty of his works can be found in the museums in Paris, Rome, Florence, Milan, Turin, Dresden, (…) London etc. The controversy that has raged from time to time over his connection with Rodin’s Balzac, makes of him an interesting subject outside of his marvelous work […]”. Charles L. Borgmeyer, “Rossos not Rodins”, American Art News 13, No. 15 (Jan. 16, 1915), 4”.

- Exhibition of Modern Italian Art. Exhibition Catalogue edited by the Italy America Society. New York: 1926.

- Elisabeth Luther Cary, “The Modern Italian Exhibition”, The American Magazine of Art 17, no. 4 (April 1926), 176.

- Helen Gerard, Radical Changes in the XVIth Venetian Biennial, “The American Magazine of Art” 20, (February 1929), 82.

- Francis Monotti, Italian Art. “Modern Painting and Sculpture in Rome”, The New York Times, June 21, 1931, 107.

- Mino Borghi, Medardo Rosso. Milan: 1950.

- Editorial. Medardo Rosso 1858-1928, «The Burlington Magazine», Vol. XCII, No. 571 (october 1950), p. 277.

- Raffaele Carrieri, Avant-Gard Painting and Sculpture in Italy, 1890-1955, Edizioni della Conchiglia/ Istituto Editoriale Domus, Milano 1955.

- The First Exhibition in America of Sculpture by Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928.

- Ibid., n. 9, illustrated in the Catalogue and n. 2, illustrated in the Catalogue.

- Ibid., n. 8, illustrated in the Catalogue. See also Dore Ashton, Art: Year’s Acquisition, «The New York Times», December 04, 1959.

- Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 17-126, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Papers.

- See Medardo Rosso, Bambino Ebreo, Detroit Institute of Arts, Bequest of Robert H. Tannahill, accession number 70.227.

- Lydia Winston acquired the sculpture Ecce Puer after flying to New York City and home on the same day to see this work which was on exhibition at the Peridot Gallery. Lydia Winston telephoned her friend, Alfred Barr in New York City and requested him and Mrs. Barr to see the piece. They promptly went to see it and Alfred Barr telephoned Lydia Winston to say: ‘It is a Masterpiece’ (December 1959). Lydia Winston Malbin Papers, Private Archive, Princeton.

- Luis Pollack to Giorgio Nicodemi, January 4, 1960. Archivio Giorgio Nicodemi, Comune di Milano.

- “Lou Pollack was […] a man of assurance, persistence and courage. He believed in the value of painting and sculpture; he believed in (certain) artists; and he believed in his own judgments. Ultimately, those judgments were based upon his sense of consistency and of what was genuine. He was himself altogether without ‘side’. Although he perforce ran a public gallery, he remained a private man and allowed no split between the two. […] The salesmanship there has been at the Peridot Gallery was a minimum response to necessity. Yet though it was never obvious, it was always certain that Lou liked and respected his artists, that he admired their work, and that his support of it and them was for him a pleasure and a satisfaction. He created an ambiance that is all too rare”. Robert Goldwater, In memoriam. Louis Pollack,1921-1970

- Lydia Winston Malbin Papers, Private Archive, Princeton.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Barr, Margaret Scolari. “Reviving Medardo Rosso.” Art News, January 1960, 38.

- Margaret Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso. New York 1963.

- Lydia Winston Malbin Papers, Private Archive, Princeton.

- See Catherine Viviano Gallery records, 1930-1990, and World House Galleries records, 1927-1991, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- Checklist October 1, 1959. James Thrall Soby Papers, The Museum of Modern Art Archives.

- The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, [exh#.426]. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers, The Museum of Modern Art Archives.

- The Italian Journey of Lydia Winston Malbin in Barzio, 1955. Lydia Winston Malbin papers, Private archive, Princeton.

- Mario Vianello Chiodo to Margaret Scolari Barr, June 2, 1960, Archivio Medardo Rosso, Barzio.

- Ibid.