Alberto Savinio: A Bridge between Metaphysical Painting and Mexican Modern Art

Carlos Segoviano Carlos Segoviano Alberto Savinio, Issue 2, July 2019https://italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/alberto-savinio/

In 1993, alongside the first exhibition in Mexico of works by Giorgio de Chirico, a parallel exhibition entitled “Metaphysics Iconography in Mexico” explored the connections between Metaphysical Painting and Mexican modern art. Omitted from this survey was the significant relationship between Alberto Savinio and the Mexican artist Marius de Zaya: both of these artists were not only considered part of Apollinaire’s creative circle but also collaborated together on projects for international magazines such as 291. This presentation investigates the reception of Alberto Savinio’s painting and art criticism in Mexico, as well as, more specifically, his connection with the artists de Zayas, Siqueiros and Antonio Ruiz “El Corcito.”

It may seem strange to write an essay that relates Andrea de Chirico, better known as Alberto Savinio, to Mexican art, given that the Greek-born Italian artist never visited “the land of the Aztecs.” There is likewise an absence of information concerning any friendships he may have maintained with promiment Mexican painters who were his contemporaries. I have identified only five translated texts about Savinio available in Mexico, which for the most part consider his literary phase and were only recently published. In 1990, with the support of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Olga Sáenz published, in her book Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica (Giorgio de Chirico and metaphysical painting), a comparative study of Savinio’s and Friederich Nietzsche’s respective philosophies, centered on the profound crisis both perceived in contemporary history and on the capacity they granted to art to present the world’s essence. Sáenz’s book provides, translated for the first time into Spanish, writings on art that Savinio published in the Rome-based magazine Valori plastici, which are, to a large extent, focused on his explanation of the metaphysical in painting:

The word metaphysic […] for the first time found in Nietzsche a free spiritual reason. […] It is no longer an indication of a post-natural hypothetical, rather […] all that prolongs the reality being […] into a calmness […] like de Chirico and Carrà, who, in fact, utilize the word metaphysics to give the right meaning to a work of visual art that relies once again on the superior understanding of the reproduced aspects.1

Savino’s ideas spread in Europe thanks to the reach of Valori plastici. This is the reason for my interest in investigating the potential relationship of Alberto Savinio and modern art in my country, as well as considering, more specifically, Mexican artists who were active on the Old Continent.

Were many Mexican artists and writers in communication with their Italian counterparts? In fact, not only were they aware of de Chirico, but, in the early twenties, artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros were making contact with figures in Europe and – precisely thanks to Valori plastici – looking at the work of Italians including Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, and Savinio himself. Manuel Rodríguez Lozano and Julio Castellanos learned of Carrà’s work in the magazine Martín Fierro in 1925, while they were staying in Argentina. These examples give some sense of how this time was an important period of convergence, and of the appropriation of iconography, particularly, in the years between the wars, by the so-called Scuola Metafisica in Mexico.

Interest in the topic of figurative painting in the interwar period is a recent phenomenon, largely considered with how metaphysical painting, as well as the Magical Realist, Novecento Italiano, and Mexican Muralist movements resisted adjusting to the avant-garde canon proposed by Alfred Barr and defined by the abandonment of figuration in favor of abstraction. Mexicans, as well as de Chirico and Savinio, deemphasized the importance of the concept of originality in modern art; their work was rooted not only in an idea of progress, but also in a return to figuration through a new approach to classical culture, especially quattrocento Italian.

In 1994, Teresa del Conde published her book Historia mínima del arte mexicano en el siglo XX (A Short History of Mexican art in the twentieth century), which highlighted the similarities between the metaphysical painting and Mexican modern art:

It happens in Mexico a bit like in Italy: the regionalisms are strong and reluctant to admit external influences. When talking about Italy I’m not referring to Futurism, which surely left echoes in Mexico, rather to the metaphysics (de Chirico founded an avant-garde, albeit against the prevailing mentality) and to the artistic movement called Novecento, which offers analogies with the Mexican School of Painting, which, like Novecento, did not configure as any school. It is more about a figurative trend of long duration that had a lot of supporters, whose individualities are well distinguishable from each other.2

In his 1940 book La pittura del Novecento (Twentieth-century painting), Ugo Nebia described the “big three” of Mexican Muralism (Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros) as among an array of international artists who were participating in the creation of a modern art in relation to a classicism that was based on an Italian mold originating in metaphysical painting and Novecento.3 Thus, in contrast to the mutual unawareness presumed to exist among Italian and Mexican artists, there were convergences of artistic approach, especially in the fantastical nature of representing memory – not necessarily related to surrealism.

It is worth recalling that Savinio, unlike his brother, kept in contact with André Breton’s group. Savinio himself denied that his oeuvre should be defined as surrealist, which brings to mind the story of Breton’s visit to Mexico and his description of Frida Kahlo as a surrealist artist, to which, after a long while, she answered: “They thought I was a surrealist, but I was not. I have never painted my dreams; I only painted my own reality.”4 Her work emanated from a reimagining of her memories and from Mexican history. For Savinio memory was similarly articulated in two directions: the individual direction of his own infancy and the history of Mediterranean civilization. Since 1920, he had differentiated metaphysical painting from oneiric material: “It is said that dreams are futile […] because dreams lack memory, because dreams lack past and future. […] Thanks to memory, when looking at images, we see what those images were and what they will become: it is the poetry of the gaze.”5

Apart from Kahlo’s work, there is a large group of Mexican paintings from this period that reflects Savinio’s words about the poetics of memory. In this sense, in October 1993, when the first exhibition in Latin America of de Chirico’s work was presented in Mexico City at the Museo de Arte Moderno, a concurrent show was organized at the museum titled Iconografía metafísica mexicana (Metaphysical iconography in Mexico); it explored, also for the first time, the relations and dialogues of metaphysical painting and Mexican modern art. In this moment it was recognized that painters such as Rufino Tamayo, María Izquierdo, and Alfonso Michel had adopted Italian metaphysics, or the creation of mysterious and silent spaces accompanied by architectures and sculptures of classical origin. However, what remained unsaid in this exhibition was that an early connection between metaphysical painting and Mexican modern art had been established by Alberto Savinio through his friendship with the Mexican artist Marius de Zayas, when they met as members of Guillaume Apollinaire’s inner circle.

De Zayas is not often included as a fundamental part of the development of Mexican modern art due to his exiled status – despite having introduced Diego Rivera’s work, as well as that of other key modern paintings, to the New York market. In the early twentieth century, due to political problems, de Zayas and his family left their native country for New York. Beginning in 1907, he partnered with Alfred Stieglitz and his famous 291 gallery, working as a curator of exhibitions, including one in 1911 on Picasso’s work and another in 1914 on African art.

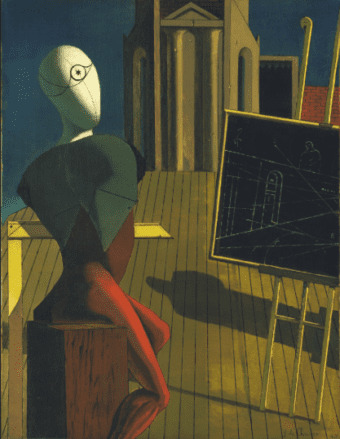

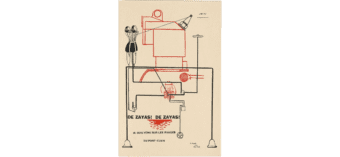

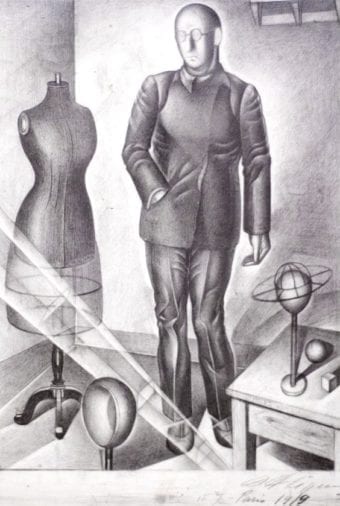

In 1913, de Zayas traveled to France to research experiments in modern art developed by the Paris School. Thanks to Francis Picabia, who had been in New York to attend the Armory Show, de Zayas had the chance to meet Apollinaire and the group of artists and literarati associated with the magazine Les soirées de Paris, among them Savinio, who had been living in the “City of Lights” since 1911. In his column in the Paris Journal, Apollinaire highlighted de Zayas’s talent as a cartoonist several times, and several of his drawings were later published in Les soirées de Paris. By April 1914, Savinio had started a dramatic poem for the opera ballet named “Les chants de la mi-mort” (Songs of the half-dead); the libretto, which consists of three main scenes, was published in the July–August issue of Les soirées de Paris. One of the main characters, “the bald man” – which may refer to the effigy with scarce hair and glasses that appears as Apollinaire’s portrait painted by de Chirico – is described as a man without voice, without eyes, and without face. This work preceded the conception of Savinio’s hybrid characters and was clearly influenced by the figure without eyes, nose, and ears in Apollinaire’s text “Le musicien de Saint-Merry,” published in the pages of Les soirées de Paris in February 1914. It was in this context of dehumanized figures that de Chirico started to include mannequins in his paintings (figure 1), just as Picabia did in a portrait of Marius de Zayas (1915; figure 2).6

Apollinaire’s poem provided an opportunity to strengthen the relationships he had developed with Savinio, de Zayas, and Picabia through their collective effort to organize a “pantomime” based on “Le musicien de Saint-Merry.” Titled “A quelle heure un train partira-t-il pour Paris?” (What time does a train leave for Paris?), it was supposed to include Savinio’s music along with a set design and staging by Picabia and de Zayas. But this adaptation, which they had hoped to present in the United States in 1915 with the sponsorship of Alfred Stieglitz and the gallery 291, was never realized due to the onset of the Great War.

Through Apollinaire and Savinio, de Zayas met Paul Guillaume, de Chirico’s art dealer, who lent a portion of his African art collection to the 1914 exhibition Statuary in Wood by African Savages, at 291. It is possible that through this interaction de Zayas became the first Mexican artist to see a painting by de Chirico, in Guillaume’s gallery. In fact, de Zayas had plans for an exhibition of de Chirico’s work to be held at the same time as the one of African art. In Stieglitz’s documents there is evidence that in November 1914, five de Chirico paintings were sent to New York, including Canto d’amore (The song of love, 1914), but they were not presented at 291.

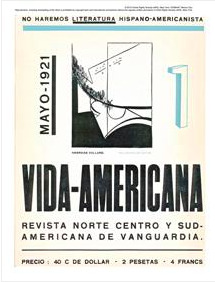

Moreover, both Savinio and de Zayas participated in magazines devoted to the Dada movement. Savinio along with Filippo de Pisis appeared as editors on the cover of the first issue of the Dada magazine Avanscoperta, published in Rome. Additionally, Savinio collaborated on the second and fourth issues of the magazine 291 (figure 3), for which de Zayas, among other personalities, was an editor. Savinio’s contributions to 291 focused on music. In 1915, de Chirico, through Savinio, sent a drawing to de Zayas for publication in 291. However, the failure of the magazine brought the relation between the Italians and the Mexican to an end. This is why a younger generation, after the conclusion of the Great War, struck up a fresh relationship with metaphysical painting, and particularly with Alberto Savinio.

In Latin America, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the consolidation of scholarship initiated aggiornamento travels to Europe. This was a moment of fully developed avant-gardes as well as the early stage of a turning point in the so-called Return to Order – post-WWI figurative painting in a classical style, through which painters such as David Alfaro Siqueiros noteably came into contact. The lifetime of the magazine Valori plastici was exactly the period during which Siqueiros was in Europe and developed his most ambitious project, the creation, in 1921, of the avant-garde magazine Vida-Americana. Revista norte centro y sudamericana de vanguardia (figure 4).

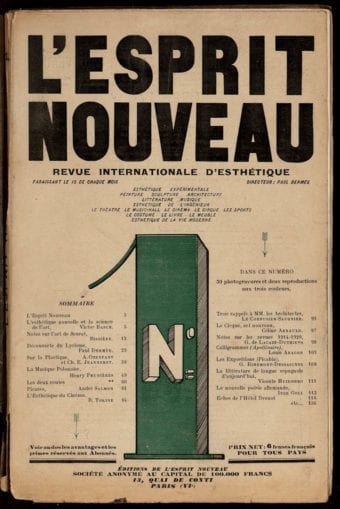

In 1919, the Mexican muralist had established himself in Barcelona. The Catalonian context offered an abundance of manifestos and short-lived magazines. These were distributed at the gallery Laietanes, which had a publications section – overseen by the poet Joan Salvat-Papasseit – that disseminated magazines that were milestones of the avant-garde, such as 291, L’Esprit nouveau (figure 5), and Valori plastici. Siqueiros reproduced texts and images from these publcations in Vida-Americana, though he did not acknowledge his sources (nor, most likely, did he request permission). Siqueiros’ magazine was clearly influenced by models including 291, and the cover design of Vida-Americana resembles that magazine. Before arriving in Europe, Siqueiros had gone through New York, where, probably thanks to de Zayas, the muralist took initial interest in movements including metaphysical painting.

In Vida-Americana, Siqueiros published a manifesto that is considered the origin and theoretical foundation of Mexican muralism, “3 llamamientos de orientación actual a los pintores y escultores de la nueva generación americana” (Three calls to the painters and sculptors of the new American generation for a new direction, 1921) – a title clearly influenced by an article published by Le Corbusier in the first issue of L’Esprit nouveau, “Trois Rappels à MM. LES ARQUITECTES” (Three reminders to architects, 1920). Siqueiros’ manifesto clearly expresses the aesthetic ideology of the “ART OF THE FUTURE.” To that end, he convened artistic programs that might seem opposed, such as the “REAPPRAISAL effort of ‘classical voices’” and the so-called futuristic in order to “live our marvelous dynamic age.”7 Strikingly, in mentioning classical voices Siqueiros recognized his proximity to metaphysical painting, and particularly its similarity to the ideas expressed by Savinio in his essay “‘Anadioménon.’ Principi di valutazione dell’arte contemporanea” (‘Anadyoménon.’ Assessment principles of contemporary art, 1919).

Siqueiros’s manifesto starts by warning young creators to drift away from flabby influences, which are more preoccupied with the decorative, just like “sick branches of ‘IMPRESSIONISM,’ just as dangerous as the official academies in which we at least learned about the classics.”8 Savinio had also criticized Impressionism. He wrote that academicism remained a skeleton nibbled on by “bureaucratic perspectives that constituted official art.”9 Further down in the Siqueiros’ manifesto, reference is made to “the comprehension of the admirable human background of ‘Dark Art,’” but a warning is also issued about falling into “unfortunate archeological reconstructions.”10 Likewise, Savinio found fault with European artists who “have nurtured themselves with the dark movement, archaism, and primitivism”11 without paying attention to the spiritual blow, for which they had only reached a formalistic reconstruction.

A central pillar of both texts is the transformation of modern art. Siqueiros points out that the decorative aspect had been a “tree pruned by PABLO CÉZANNE, the restorer of the essential,”12 because it was thanks to him that all the spiritual restlessness about modern art renovation emerged. In a similar tone, Savinio wrote that pictorial art “gradually lacked all spiritual refreshment,” until “Cézanne undertook new lines” as “head of the period of renewal,”13 a situation that led to a new classicism, metaphysical painting, and the recovery of a spiritual vitality in its plastic limits that had been lost in the academicism of classicism. Likewise, Siqueiros encouraged the “reintegration of the MISSING VALUES of painting and sculpture […] just like the classics, let us carry out our work within the inviolable laws of aesthetic balance!”14

Siqueiros was also influenced by Carlo Carrà’s work, as suggested by a drawing he published in Vida–Americana that features a living mannequin in a suit, resembling Carrà’s metaphysical automaton dressed in modern clothes. Here, Savinio’s stance regarding the mannequin figure is relevant. In opposition to electrical marionettes – divested of emotion by Marinetti – Savinio proposed a being that had a metal antenna head and a tripod for legs, but possessed a great heart. Like Pinocchio, this metaphysical automaton would have been capable of making moral decisions and, most of all, sensing a superior reality.15 In his drawing, Siqueiros represented William Kennedy Dickson, an inventor – not a tailor, as the painter himself noted in his autobiography (figure 6).16 In reality, what Dickson “sewed” were moving images produced by a Kinetoscope, a technological mechanism giving rise to an illuminated prism at the corner of the artwork, suggestive of movement and futurism. Siqueiros opted for an almost anonymous metaphysical character, or entity, capable of presaging a more advanced world.

However, upon his return to Mexico, Siqueiros strove for the creation of art in a nationalist style, and this apparently led him away from the European avant-gardes. At this point, there arose another group of writers and painters – designated as contemporáneos, or “contemporary,” by a Mexican magazine of that name specializing in literature and art between 1928 and 1931 – who showed interest in the appropriation of Italian metaphysical painting among various literary and plastic movements of early twentieth-century Europe. Of this group, the painter Antonio Ruíz demonstrated a considerable affinity with Savinio; known as “el Corcito” or “el Corzo” (the little roe deer),17 Ruíz, like Frida Kahlo, oscillated as a painter between political criticism and otherworldly figuration closer to metaphysical painting.

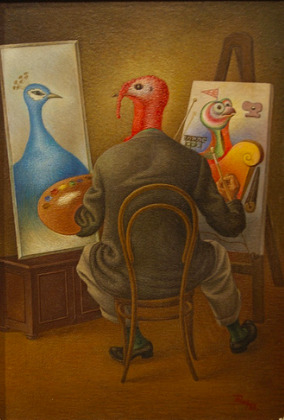

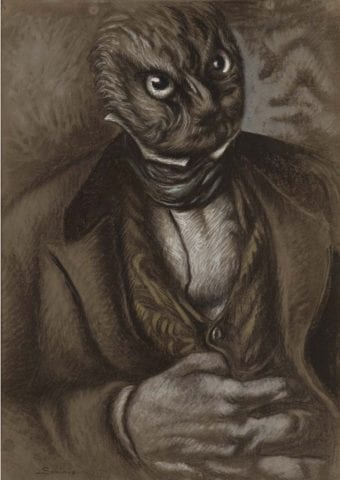

When Ruíz’s work addressed political issues, it did so with an irony that did not deny the fantastical to reaffirm denunciation. For instance, the sarcastic painting El líder/orador (The speaker, 1939) manifests as a humorous interpretation of a leader who takes advantage of the ignorance of unionized workers, represented as pumpkins. In this respect, Ruíz was aligned with Savinio, who also assigned great importance to irony: “In painting, irony has a place of utmost importance when the artist reaches its peak of clarity […] that makes the artist, in spite of himself, deform somehow, when reproducing them, the terribly clear aspects that he perceives.”18 Savinio’s ironic images drew on the grotesque of the thirties, in which human figures appeared with animal heads. In Marche Nuptiale (Wedding march, 1931; figure 7), the figures have the heads of a giraffe, a rooster, and a turkey, recalling Ruíz’s Self-portrait (1936; figure 8). In the latter, Ruíz, represented with the head of a turkey, Savinio also made a self-portrait as a bird, specifically an owl (Autoritratto in forma di gufo [Self-portrait as an owl], 1936; figure 9).

At the moment, Ruíz’s knowledge of Savinio’s painting is unverified. Nonetheless, the Mexican artist created what is probably the first painting in his region that can be related to Italian metaphysical painting, Alegoría teatral (Theatrical allegory, 1923; figure 10). This picture presents different, unconnected objects, some of which are characteristic of the iconography of metaphysical painting (i.e. the classical temple, the living statue, and the plastic, enigmatic value assigned to shadows). De Chirico, Savinio, and Ruíz were all linked to theater. Perhaps their tendency towards images that were both realistic and fantastical suggests that, even if the de Chirico brothers and Ruíz never met, they certainly shared ideas and procedures.

Bibliography

Bohn, Willard. Apollinaire and the Faceless Man: The Creation and Evolution of a Modern Motif. Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1991.

del Conde, Teresa. Historia mínima del arte mexicano en el siglo XX. México: ATTAME ediciones, 1994.

de la Rosa, Natalia. “Vida-Americana 1919–1921.” Artl@s Bulletin 3, no. 2 (Autumn 2004): 22–35.

Herrera, Hayden. Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: Harper & Row, 1983.

Nebbia, Ugo. La pittura del Novecento. Milan: Società editrice libraria, 1941.

Savinio, Alberto. “‘Anadioménon.’ Principi di valutazione dell’arte contemporánea.” Valori plastici 1, nos. 4–5 (April–May 1919): 6–14.

Savinio, Alberto. Primi saggi di filosofia delle arti II.” Valori plastici 3, no. 3 (May–June 1921): 51–53.

Sáenz, Olga. Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1990.

Siqueiros, David Alfaro. “3 llamamientos de orientación actual a los pintores y escultores de la nueva generación americana.” Vida-Americana. Revista norte centro y sudamericana de vanguardia, no. 1 (May 1921): 1–3.

How to cite

Carlos Segoviano, “Alberto Savinio: A Bridge between Metaphysical Painting and Mexican Modern Art,” in Alberto Savinio, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 2 (July 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alberto-savinio-a-bridge-between-metaphysical-painting-and-mexican-modern-art/, accessed [insert date].

- Alberto Savinio, “‘Anadioménon.’ Principi di valutazione dell’arte contemporanea,” Valori plastici 1, nos. 4–5 (April–May 1919): 6–14; republished in translation in Olga Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica (México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1990), 112. All translations from the Spanish are by Jorge Tovar.

- Del Conde, Historia mínima del arte mexicano en el siglo XX (México: ATTAME ediciones, 1994), 11. English translation by Jorge Tovar.

- Ugo Nebbia, La pittura del Novecento (Milan: Società editrice libraria, 1941), 305.

- Frida Kahlo quoted in Hayden Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), xi.

- Alberto Savinio,“Primi saggi di filosofia delle arti II,” Valori plastici 3, no. 3 (May–June 1921): 51–53; republished in translation in Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica, 126. English translation by Jorge Tovar.

- See Willard Bohn, Apollinaire and the Faceless Man: The Creation and Evolution of a Modern Motif (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1991), 89.

- David Alfaro Siqueiros, “3 llamamientos de orientación actual a los pintores y escultores de la nueva generación americana,” Vida-Americana. Revista norte centro y sudamericana de vanguardia, no. 1 (May 1921): 1. English translation by Jorge Tovar.

- Ibid.

- Savinio,“Anadioménon,” in Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica, 112.

- Siqueiros, “3 llamamientos de orientación actual,” 2.

- Savinio,“Anadioménon,” in Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica, 112.

- Siqueiros, “3 llamamientos de orientación actual,”1.

- Savinio,“Anadioménon,” in Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica, 111 and 115.

- Siqueiros, “3 llamamientos de orientación actual,” 1.

- Alberto Savinio, “Dramma della città meridiana,” in Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica, 137.

- Natalia de la Rosa, “Vida-Americana 1919–1921,” Artl@s Bulletin 3, no. 2 (Autumn 2004): 22–35.

- The nickname of “el Corzo” is due to his physical resemblance to a Spanish bullfighter named Manuel and surname Corzo, also called “el Corcito” because of his youth.

- Savinio,“Anadioménon,” in Sáenz, Giorgio de Chirico y la Pintura Metafísica, 119.