Upon exiting the Giorgio Morandi exhibition at the Center for Italian Modern Art last November, Dutch artist Jan Dibbets returned to one of Morandi’s late paintings, an almost-square, beige-on-beige Still Life, 1963, and murmured: “This is the perfection of what Morandi pursued over 50 years!” Cutting through the silence Dibbets kept along his visit, this comment opened the space for us to ask him—a pioneer conceptual artist, who abandoned painting in 1967 to never go back to it—about his interest in Morandi—the quintessential painter. Why was the Dutch so enthralled by the Italian? So Dibbets remembered his student years. For an artist coming to maturity at the turn of the 1960s, he explained, there were only few painters that stood out as a viable alternative to Abstract Expressionism and from whom one could learn it all, first and foremost Giorgio Morandi and Robert Ryman.

With Robert Ryman on view at Dia:Chelsea through June 18, 2016, this year New Yorkers can enjoy masterful exhibitions of both painters. The show displays 22 works that American artist Robert Ryman (b. 1930) realized between 1958 and 2002, intelligently installed over two unequally sized galleries bathed from above with mutable natural light, contributing to make this small selection of works surprisingly rich in their variety of materials, gestures, and effects. Rather than following a typical linear development, Ryman’s oeuvre circles around one same concern. As Morandi imposed on himself a limited vocabulary of forms, Ryman has famously reduced his palette to the color white and his surfaces to squares. Yet these limitations become Ryman’s strength, as the Dia show beautifully demonstrates. For over fifty years, the artist has systematically investigated, in his own words, “never what to paint, but only how to paint.” His works surprisingly multiply the spatial effects of white by ranging broadly in modes of paint application, assorted support and surface materials, and repertoire of hanging devices.

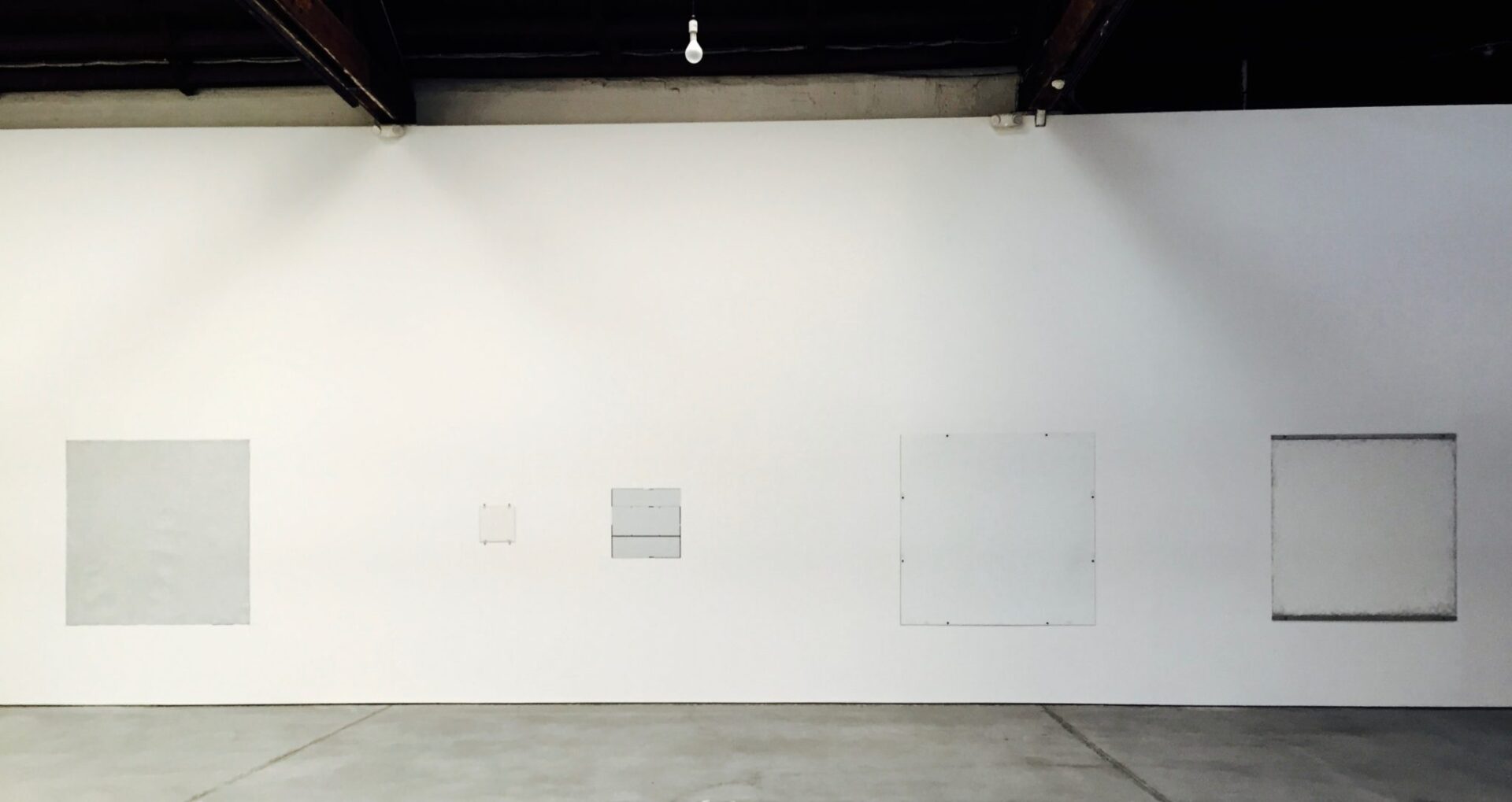

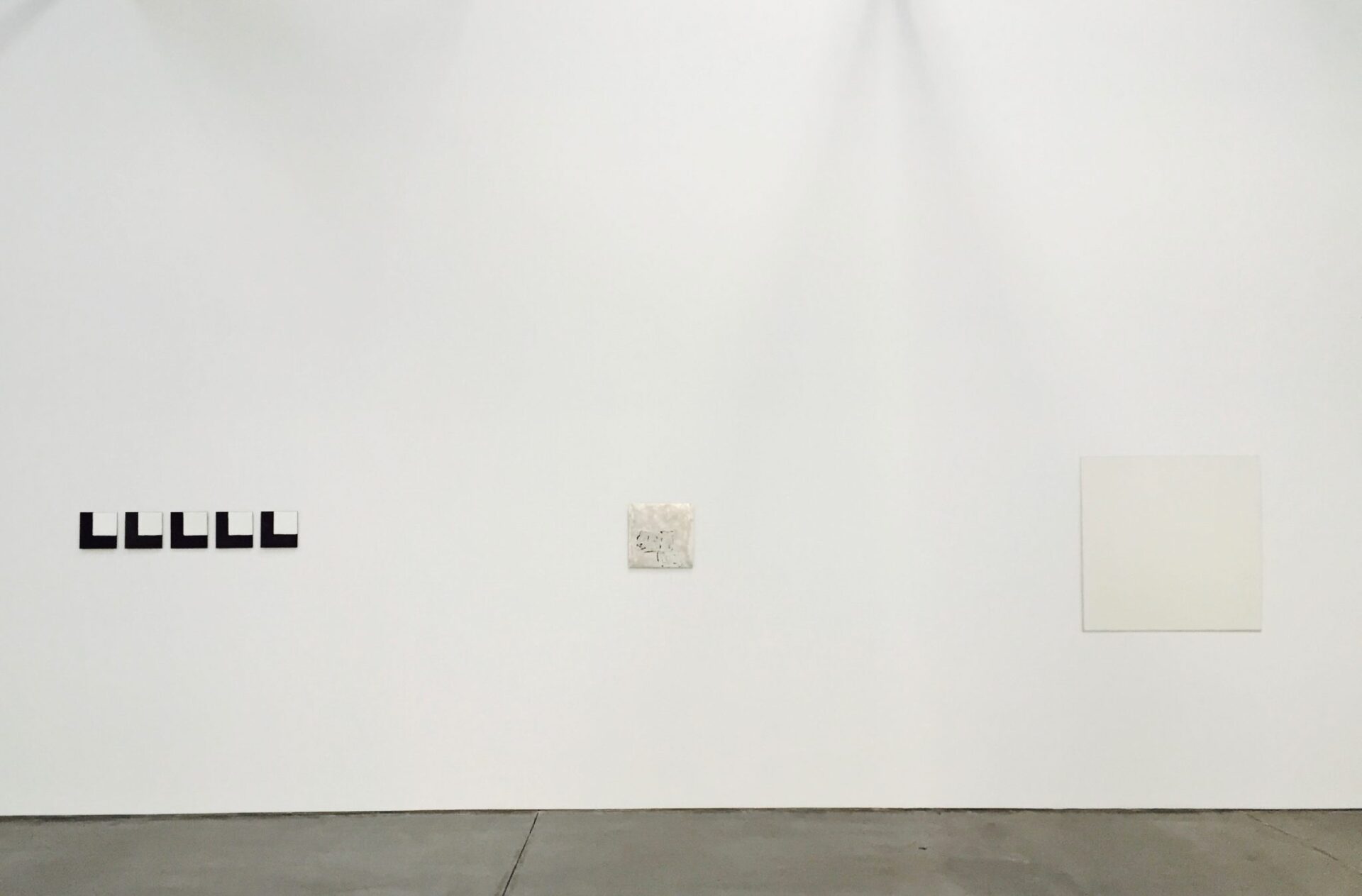

The first gallery at Dia:Chelsea feels narrow, with a couple of large square canvases to the right (Untitled, 1962 and Untitled [Background Music], 1962), a triplet of works incrementing in size and respectively on canvas, paper, and plywood to the left (Untitled #17, 1958; Classico 6, 1968; Counsel, 1983), and a small but powerful early work facing the viewer across the room, decentered (To Gertrud Mellon, 1958). The forced proximity to the paintings commands close scrutiny, which in turn is constantly deferred by the variable light conditions, making it impossible to pin down a detail without seeing it change in front of your eyes. From here, visitors transition into the much wider second gallery. The regained breath of space allows taking in with one glance each of the gallery walls, where works are knowingly grouped so to highlight, respectively, the heterogeneous material supports Ryman used, the attention he gave to the joints between the painting and its backdrop, the manifold modes of paint application, and the muted nuances coming across layers of his signature white paint.

The show at Dia:Chelsea, moreover, triangulates in space and time the institutional history of Dia Art Foundation. It evokes Ryman’s first solo show at Dia Center for the Arts in 1988-89, thus reactivating at once Dia’s longtime relationship with the artist and its historical presence in the neighborhood. Between 1987 through 2004, in fact, Dia occupied the building at 548 West 22nd Street, that is, just across its current project spaces at 541-545 West 22nd Street. Ryman himself contributed to the design of the 1988 exhibition, setting the model for measuring galleries against his paintings and letting natural light filter through windows and skylights during daytime. Across space, the current show links the new outpost in Chelsea and Dia:Beacon, the exhibition complex an hour north along the Hudson River. Since its establishment in 2003, a substantial body of works by Ryman in Dia’s collection has been on display in Beacon, lit during daylight hours with natural light only.

Robert Ryman was born in Nashville in 1930. In 1952 he moved to New York City intending to pursue a career in jazz, yet shortly thereafter he picked up painting instead. His earliest production demonstrates his love of and early departure from Abstract Expressionism, as seen in works currently on view at Dia:Chelsea such as Untitled, 1962 and Untitled [Background Music], 1962. Here, Ryman voids the all-over gestural mark of Abstract Expressionist painters of any subjective referent, and each one of the red, blue, and white brushstrokes denote calculated mechanical decomposition of the color palette rather than immediacy. Meaning in Ryman’s works is therefore often given through elusive titles that function as appendix to the work. The artist had his first solo exhibition in New York at Bianchini Gallery in 1967, and from then on his career grew internationally. Ryman began to experiment with different supports, moving from board, canvas, and paper to aluminum, fiberglass, and Plexiglas. Concurrent to conceptual art, Ryman started giving visibility to the hinges and fasteners that correlate paintings to gallery walls—and, by extension, to their institutional context. Exemplary of this, works on view at Dia:Chelsea range from Arista, 1968, an unstretched canvas stapled to the wall (Gallery 2, east wall), to Pair Navigation, 1984/2002, resting on a wooden panel elevated on aluminum rods parallel to the floor (Gallery 2, north wall).

Robert Ryman is a wonderful reminder of the historical importance of the artist, who bridged Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Post-Minimalism. Moreover, his work resonates with the liveliest contemporary practice, finding a place of honor within the current discourse about the medium of painting.