Laura Moure Cecchini, a current PhD candidate at Duke University, is CIMA’s first Travel Fellow. This is the second in a series of occasional posts on the research she is conducting in Italy.

The National Central Archive or Archivio Centrale dello Stato (ACS), hosted in a monumental building in the EUR neighborhood, can be quite intimidating for its breadth and complexity.

It has nonetheless proven a key asset for those chapters of my dissertation that deal with the fascist period. Indeed, scholars of interwar art must take into account the intertwinement of politics and culture in that period, and therefore the active role that the state played in the arts. Most of this documentation is held in the folders pertaining to the Divisione Antichità e Belle Arti (Division of Antiquities and Fine Arts), a section of the Ministry of Education (AABBAA). Here one can find essential information on the functioning of public museums, such as the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna of Rome, the Galleria Corsini, or the Museo Mussolini; on state-sponsored organizations such as the Venice Biennale or the Roman Quadriennale; and on exhibitions of Italian art in cities such as London, Bruxelles, or Paris, among many other themes. Another section of the archive that has important information for art historians are the records of the Fascist Party or Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF). As many of the exhibitions at the time were directly managed by the party – such as the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista – their photographic and archival documentation is held here.

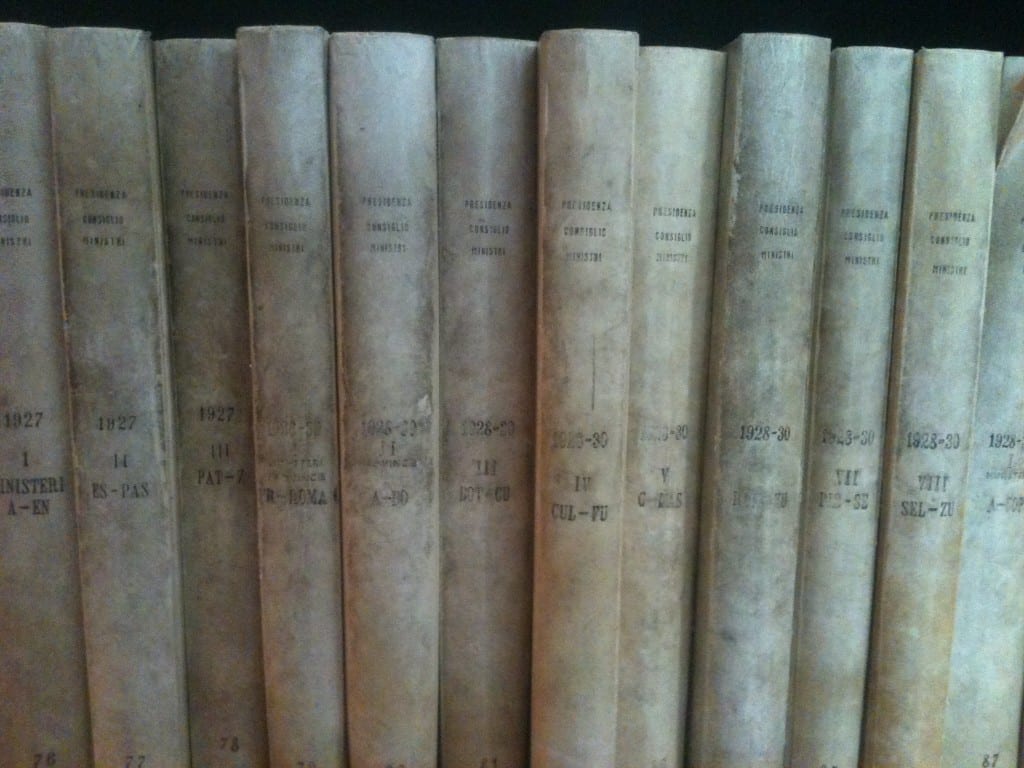

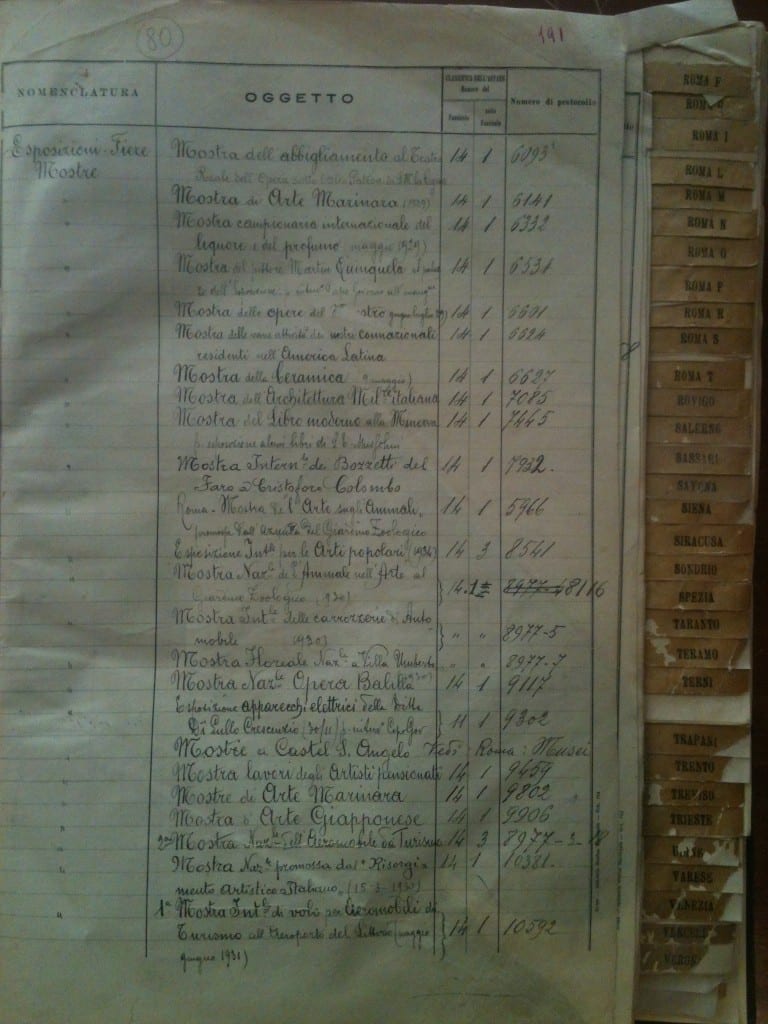

As might be expected of a totalitarian state, the vast majority of cultural and artistic manifestations during the interwar period required official authorization or endorsement. Therefore, the research of scholars of fascist art is aided by consulting the records of the Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministry (Presidency of the Council of Ministers or PCM). Information on these matters was transcribed in enormous notebooks, divided by year. Here, in alphabetical order, are listed all the issues that were brought to the attention of Benito Mussolini, from the organization of exhibitions to the appointment of cultural officials, from the construction of public buildings to the urban transformation of cities. No matter was considered irrelevant. For example, in the years 1929-1930 the Duce was informed on the progress of the organization of the Venice Biennale, but also on shows of “Animals in Art,” organized in the Roman zoo, or on an exhibition of planes in the airport of Rome.

Another key source for information on art during the fascist period is the correspondence with the Secreteria Particolare del Duce (Private Secretary of the Duce or SPD). Every person who corresponded with Mussolini’s office has a numbered file with his or her letters and personal information. Therefore, a search by name in the classifying files leads to important discoveries on the relation between leading artists, architects, and cultural players, and the regime. It is also possible to do a search by topic, such as “Biennale” or “Quadriennale” —by doing this, I came across important background information on the organization of some interwar shows that pertain to my research.

The ACS also preserves the personal archives of artists like Carlo Levi, and of public officials such as Palma Bucarelli, the formidable director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna from 1941 to 1975, and as such one of the key players of Italian postwar art. The ACS is a precious resource for the study of architecture and engineering in Italy and its colonies oversees, as it has a collection of archival material, photographs, and architectural models by architects like Pietro Lombardi, Luigi Moretti, Mario Leonardi, and Gaetano Minnucci, among many others.

Although the amount and complexity of information available at the ACS can seem overwhelming, all the librarians and archivists who work there have been extremely helpful. They patiently guided me throughout the meandering paths of the archival organization, and aided me in retrieving the documents I needed. They also suggested alternative records, where I was able to find key information. Unlike other Italian archives, the ACS allows researchers to photograph the material with their own camera, for a nominal fee.