In 2014-15 CIMA launched a new fellowship, to support a scholar traveling to Italy for the purposes of research or study. CIMA’s inaugural travel fellow is Laura Moure Cecchini, a PhD candidate at Duke University. This is the first of a few posts she will contribute on the research she is currently conducting in Italy.

A visit to the archive of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (GNAM) in Rome is essential for researchers of Italian modern art, and therefore it was one of the first stops during my CIMA travel fellowship. Created in 1946 and now directed by Dr. Claudia Palma, the archive comprises three distinct sections. The oldest one is the “Archivio Bio-Iconografico” (Biographical and Iconographical Archive). Overseen by Dr. Stefania Navarra, it includes files with the press releases for Italian and foreign contemporary artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For example, if one wanted to trace the critical response to the work of the Milanese sculptor Adolfo Wildt—a major figure in my dissertation—the Archivio Bio-iconografico is a precious resource, because it has preserved newspaper clips and journal articles on this artist from the 1930s up to the present. Although these files sometimes do not include every single review of an artist, and therefore a trip to a periodical repository is unavoidable, the Archivio Bio-iconografico represents a precious resource because it contains articles that have appeared in periodicals with low circulation and are therefore hard to find elsewhere. It is also very useful not only for scholars of Italian art, but also for those who study the reception of foreign art in Italy because it preserves records for non-Italian artists who exhibited in the country.

The second important section of the archives in the GNAM is the “Fondi Storici,” that is, the personal archives of important figures of Italian modern art, which is managed by Dr. Clementina Conte. Among the ones that I have consulted are the records of Antonio Maraini and Ugo Ojetti, key figures of interwar Italian culture. Maraini, who was the Secretary General of the Venice Biennale and the Commissar of the Fascist Syndicate of Fine Arts, as well as a renowned sculptor, saved important material on all aspects of his career. The Fondo Maraini, therefore, is rich in information on the Venice Biennale, on the organization of exhibitions in and outside of Italy, on public commissions during the 1930s and 1940s, etc. In addition to correspondence and documentation, Maraini also preserved press releases and reviews of the exhibitions he participated in and organized, which are very valuable for students of interwar art.

Ojetti was also an important player in Italian cultural policy of the first half of the twentieth century. As the art critic of the Corriere della Sera, one if not the most important Italian newspaper, Ojetti participated in the key artistic debates of the time. The Fondo Ojetti in the GNAM contains Ojetti’s correspondence with artists, critics, and politicians—most of which is still unpublished. I have reviewed Ojetti’s exchanges with personalities such as the neobaroque architect Armando Brasini and the critic Margherita Sarfatti. Another important section of Ojetti’s archive is in the Biblioteca Centrale di Firenze; here are Ojetti’s first drafts of his articles and books, as well as other sections of his correspondence. The Archivio Alessandro Bonsanti, which is in Florence as well, preserves Ojetti’s collection of books.

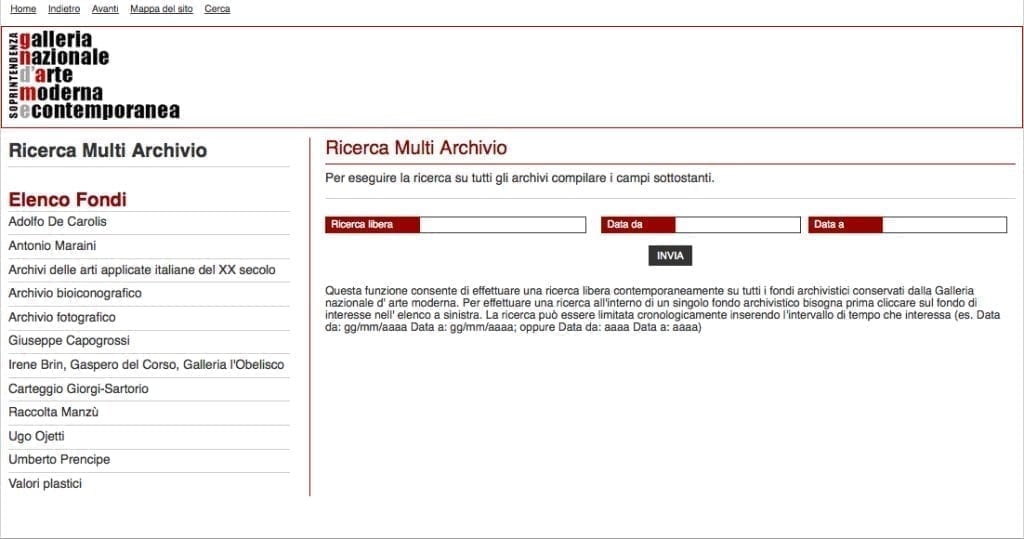

In addition to the aforementioned records, the GNAM also has collections on the Valori Plastici group, the art dealer Irene Brin, the artists Adolfo De Carolis, Giuseppe Capogrossi, and Umberto Prencipe, as well as a collection of documents on Italian applied arts of the twentieth century. The content of these collections has been catalogued and is easily accessible on the GNAM website (click on the name of the archive that you want to consult on the left, and then on “Fondo” on the right to access its structure and contents).

Finally, the GNAM’s third important section includes a little explored archive, the Archivio Storico della Galleria, which is the documentation of the history of the museum itself. At the moment this archive is being re-organized and catalogued by Dr. Cristina Tani, but she was fortunately and kindly able to retrieve all the documents I needed. This archive is very useful for scholars of institutional art history, because the GNAM has organized crucial exhibitions of modern art over the past century, and since its foundation in 1883 it has been tasked with collecting the most valuable examples of Italian art, from neoclassicism to the contemporary period.

Drs. Conte, Tani, and Navarra went out of their way to help me find all the documents I needed. For a small fee, it is possible to photograph unpublished documents for study purposes. The reproduction of published materials (newspapers, journals, books) is, on the contrary, free.

In my next blog post I will be reporting from the Archivio Centrale dello Stato, the quite daunting National Central Archive where I have found crucial material for my research.