Written by CIMA Spring intern, Elisa Pellegrini.

On March 19th, CIMA members were invited to visit the exhibition entitled Hilma af Klint: Painting for the Future, on view through April 23, 2019 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. The group had the chance to attend a private tour led by the curatorial assistant David Horowitz.

As the curator of the exhibition Tracey Bashkoff notes: “Hilma af Klint’s abstract work predates the work by artists such as Kandinsky, Mondrian, Kupka, Malevich, artists that we have long considered the pioneers of abstraction. She begins working in an abstract mode as early as 1906.” Indeed, influenced by the spiritual movements and scientific discoveries of her era, af Klint tried to represent the world beyond what the eye can see, expressing abstract concepts. However, af Klint was convinced that the world was not yet ready to understand her work. Consequently, while many of her better-known contemporaries published manifestos and exhibited widely, she kept her innovative paintings largely private, rarely exhibiting them.

The artist decided that her work was not to be shown for twenty years following her death. In this way, its contemporary reception becomes a rare opportunity to rethink art history, demanding a re-evaluation of the timeline and of the key figures of abstraction’s development in the early twentieth century. Af Klint’s background and training were strongly connected to traditional drawing and painting. Born in Sweden in 1862 and raised in a middle-class family in Stockholm, she studied at the city’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, which later granted her a free studio. The artist made botanical drawings, painted landscapes, contributed illustrations to scientific journals, and made portraits on commission – all common artistic pursuits of the period.

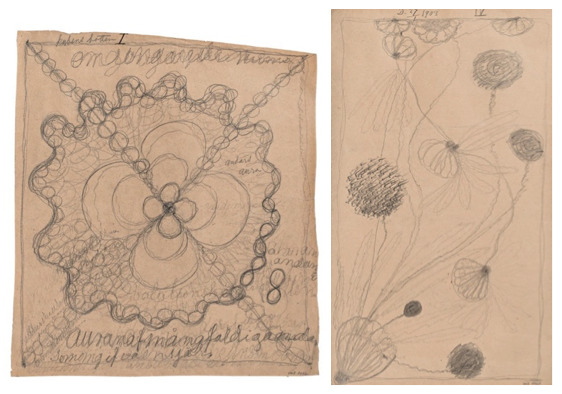

Later, af Klint left Stockholm’s art world to concentrate entirely on pursuing her spiritual, and largely abstract, style. As many of other artists of that time, she was deeply involved in spiritualism, believing in the ability to communicate with spirits in another realm. In the 1890s, af Klint began meeting regularly with four other women who shared her beliefs. They called themselves The Five (De Fem) and, as other spiritualists of the era, they thought that their work was a way of obtaining direct access to a higher order of knowledge. The women produced automatic drawings, imagining that a spiritual guide was on their side and using this technique to communicate with another world. Through these exercises, af Klint abandoned the confines of her academic art training, envisioning an abstract and original imaginary.

In 1904, during séances, two of the spiritual guides that The Five regularly channeled introduced the idea of a temple that would one day be built to house a series of spiritually derived paintings. The five women were called to complete the task but af Klint was the only one to accept. Indeed, the others were worried that such an intense engagement with the spiritual realm could lead to madness and they cautioned af Klint to consider carefully before accepting. However, in January 1906 af Klint agreed to carry out the project and she defined that “the great commission.”

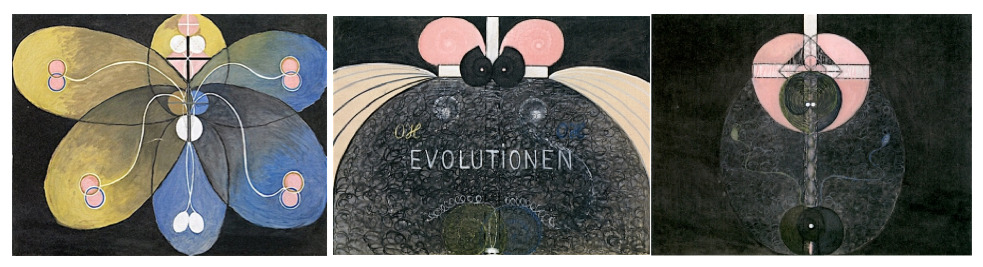

In 1906, working on The Paintings for the Temple, af Klint officially turned toward spiritual subject matter, abandoning figuration. It is with these paintings that art and spiritualism found their conjunction in af Klint’s work. In these artworks and even more in Evolution, we can see the evolution theme: according to Theosophical thought, evolution is a process that extends beyond biology, pervading the cosmos on physical and ultimately spiritual levels. In Evolution, spiritual development is represented in the progression from one canvas to the next, while evolution’s specific role in this process is delineated by the form of the spiral, a symbol of continual growth and change, embodied in the snail’s shell. Early in the group, snails can be seen at the lowest level, at the point of renewal; their subsequent rise is captured in the final paintings.

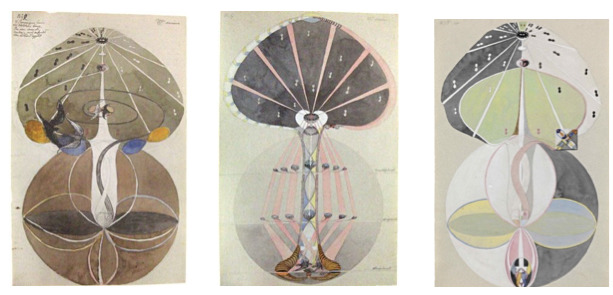

In the following years af Klint paused her work on The Paintings for the Temple to care for her mother, who had gone blind. When she returned to the project, her approach was changed and, instead of experiencing a spirit acting through her, she perceived messages and she decided how to interpret and express them. This shift is visible in her changed style. Indeed, religious iconography increased, geometric forms became emphasized, and freely moving lines began to appear less frequently. However, some of af Klint’s earlier motifs, such as spirals, abstracted plants and animals, and imagery derived from science and esoteric belief systems, remained prominent. We can see these subjects in The Three of Knowledge, where the artist offered a visionary interpretation of the biblical narrative of the Garden of Eden.

Af Klint created thematically and formally focused groups. Indeed, her idea was to create groups of paintings that where connected to each other, where there was a specific order and a relationship between the compositions. For example, this is visible in The Swan, where this kind of structure gives the sensation that the canvases are two subsequent frames of a filmstrip. In No. 1 duality is the main protagonist of the painting: the white and the black swan represent light and dark, male and female, life and death, forces whose opposition and eventual resolution were central to existence, according to af Klint. In alchemy, the swan symbolizes the union of opposites necessary for the creation of the philosopher’s stone, a legendary substance capable of turning base metals into gold. In the paintings, these forces embodied by the swans come into conflict and then combine, a process signaled by the shift from representational to abstract imagery. The circle lines drag the audience to the center of the painting where the forces meet.

Later, in 1920, af Klint joined Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society, an offshoot of the Theosophical Society that emphasized the accessibility of the spiritual realm through introspection and personal development. Af Klint had the chance to encounter Steiner already in 1908, when she invited him to her studio in Stockholm to see The Paintings for the Temple, that were not still complete. Steiner’s reaction disappointed af Klint. In fact, although he appreciated her use of symbolism, he disapproved of her mediumistic approach and encouraged her to rely more on introspection. At the time af Klint decided not to follow Steiner’s model of art making but in the early 1920s she began to incorporate his preferred wet-on-wet watercolor technique into her artistic practice. As she continued to focus on the presence of the divine in nature and flouted Steiner’s prohibition against using black, it is still distinctly visible her style.

When Hilma af Klint had completed the works for the Temple, the spiritual guidance ended. Nonetheless, until her death in 1944, she continued to push the bounds of her new abstract vocabulary and spiritually derived subjects, as she experimented with form, theme and seriality. Throughout her life, af Klint tried to represent a transcendent reality beyond the observable world and she tried to understand the mysteries that she had come in contact with through her work, leaving behind more than 150 notebooks with her thoughts and studies.

Hilma af Klint: Painting for the Future is the first major solo exhibition in the United States devoted to the artist and it is able to reveal the work of an “artist who was both of her time and decisively ahead of it”.