Written by CIMA fall intern Nicole Boyd.

For audiences in Italy and the US alike, the term “neorealism” most often brings to mind cinematic masterpieces, affecting films of the mid-twentieth century – such as Roberto Rosselini’s Roma città aperta (Rome, Open City) and Vittorio de Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) – that portray the conditions of everyday life in Italy following World War II.

On the morning of November 14, 2018, members of CIMA were invited to challenge their perceptions of this movement on a private tour of NeoRealismo: The New Image in Italy – an exhibition curated by Enrica Viganò which, after traveling to various institutions throughout Italy, was mounted at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, as well as the Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò, from September 6 to December 8.

In NeoRealismo, cinema takes a back seat. Though, to the delight of movie buffs, references to touchstone films (i.e. a poster advertising De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette) are speckled throughout, the show’s primary concern was Italian photography executed between 1932 and 1960. The exhibition, in this sense, defies popular understanding of neorealism in two respects: it asks viewers to conceive of the movement as a creative approach that not only manifested in various facets (rather than just one) of visual culture, but also originated several years before the 1950s (the decade commonly recognized the peak of neorealism).

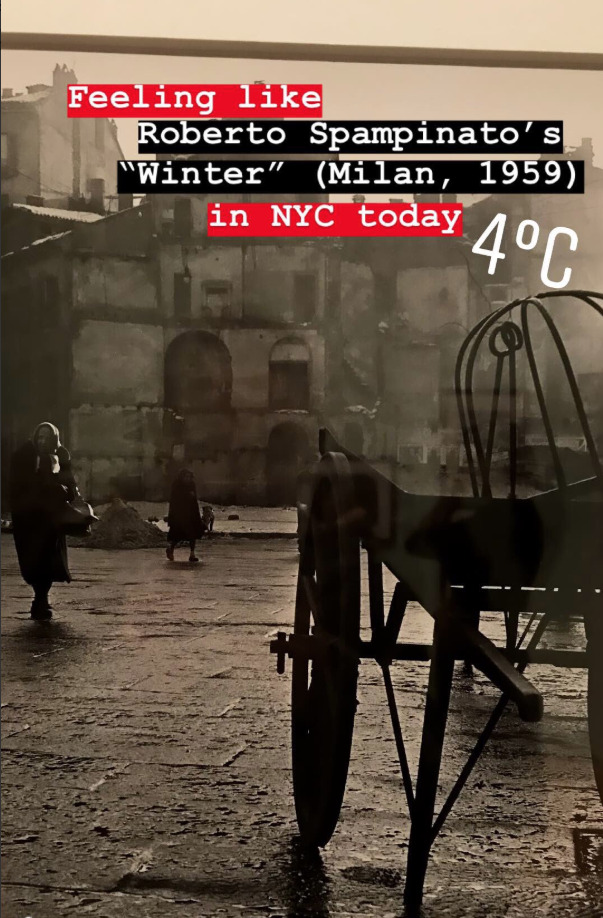

CIMA members (and staff) arrived at Grey Art Gallery around 11am, eager to escape the inclement weather (it was unusually frigid and windy for early November), and were promptly greeted by Graduate Curatorial Assistant English Cook. As our tour guide, Cook expressed that her main goal was to inspire dynamic, inclusive discussions about the images and themes presented in NeoRealismo, and she continually reminded the group of this intention while moving throughout the gallery. Upon arriving at any given photograph, Cook would not spring into a one-sided lecture. After briefly offering some background information, she would rather ask questions – about what we saw, how we felt, or how the image under scrutiny compared (in terms of composition, subject, tone, etc.) to others we had already observed.

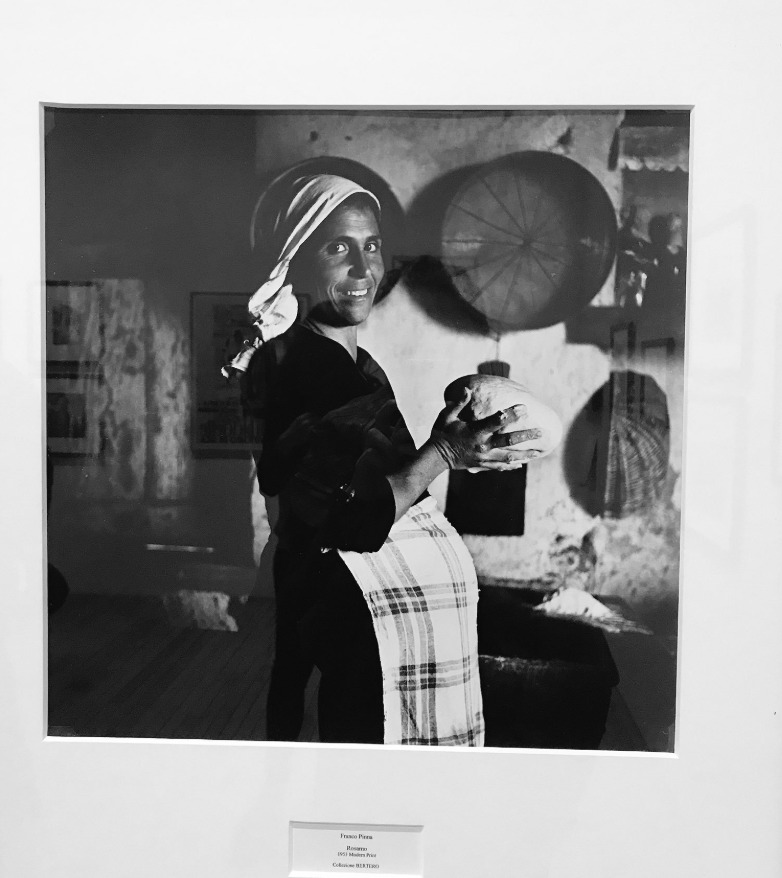

Progressing through NeoRealismo in this conversational fashion, we were acquainted with the exhibition’s five sections, which, we were told, had been installed according to theme. The first section (‘Realism in the Fascist Era’) included pictures that express how the Fascist regime manipulated the medium of photography to convey propagandistic messages to the masses, including Italy’s vast illiterate population. Meanwhile, the second section (‘Poverty and Reconstruction’ encompassed images, by photographers as well as filmmakers, that juxtapose the struggles of postwar life with the country’s optimism for the future

Conceived after the fall of the Fascist regime, the media displayed in the remaining three sections largely respond to the state of the Italian nation in the postwar period. ‘Ethnographic Investigations’ included images, shot in various parts of the Italian peninsula, that demonstrate the efforts of photographers to construct a collective Italian identity from the country’s many faces and regional cultures. ‘Photojournalism and the Illustrated Press’ encompassed photographic narratives in newspapers and magazines that – being published during the purported “golden age” of neorealism in film – evoke cinematography. Finally, ‘From Art to Document’ centered on the establishment of photo clubs where members debated the value of photography as an artistic medium and ultimately gave rise to two opposing schools of photographic criticism.

Cook sparked a collective curiosity among CIMA’s members. Many were eager to continue navigating the gallery independently, while others lined up to ask questions about photos and themes that were not covered during the tour. Through my own conversation with our guide, I gathered that this sort of inquisitiveness is shared by scholars, like the aforementioned Enrica Viganò, who have endeavored to research neorealism’s photographic roots. This area of study is, after all, young and, according to Cook, ripe with unanswered questions.