The Archives of American Art has become a key repository for CIMA fellows. Although focused on American art, it turns out to be a tremendous resource for scholars investigating the entry and impact of Italian art in the US in the twentieth century. Here CIMA Fellow Chiara Fabi shares her experiences with the AAA.

The Archives of American Art has become a key repository for CIMA fellows. Although focused on American art, it turns out to be a tremendous resource for scholars investigating the entry and impact of Italian art in the US in the twentieth century. Here CIMA Fellow Chiara Fabi shares her experiences with the AAA.

The Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution is a complete surprise for a foreign researcher. When you are used to doing research, you know very well the difficulties of this job: a lot of patience is required, and you must constantly ready yourself to discover that the letters of an artist or an art gallery have gotten lost over the years. For these reasons, the richness and vast assets of the Archives of American Art came as a really positive surprise to me!

Founded in 1954 as a microfilm repository of papers housed in other institutions, the Archives of American Art encompasses today over 20 million items; and it is continually growing and adding collections. It is, according to their website, the “the world’s largest and most widely used resource dedicated to collecting and preserving the papers and primary records of the visual arts in America.”

Actually there are two different offices of the Archives of American Art available to scholars: one is in New York, which houses microfilmed collections, and the other is in Washington DC, where all the original materials are located; at both places, managing your reservations is easy, as is the consultation, and the reference staff is friendly and helpful. Moreover, since 2005 AAA has been scanning some of the most significant collections and placing them online.

The Archives of American Art, both in New York and Washington, were crucial to the success of my CIMA fellowship. Each year CIMA offers a series of six-month fellowships to art historians, open to any nationality. You can be working on your own research, but you must propose a project that intersects with the artist being studied for that year.

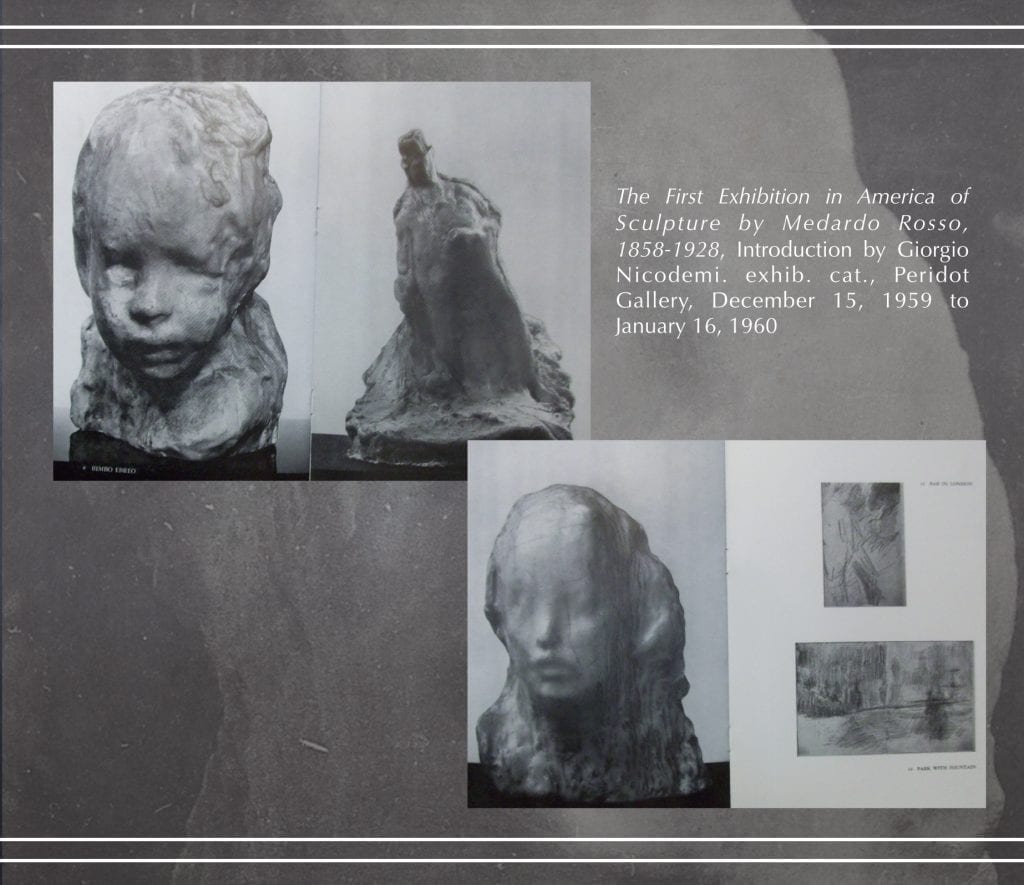

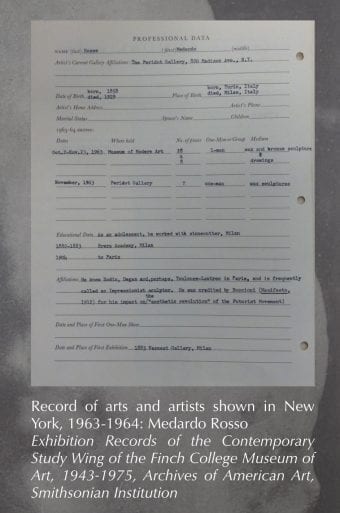

The 2014-15 season is focused on Medardo Rosso, and I was investigating the entry of Rosso’s sculptures into the U.S. in the years after World War II. I was particularly interested in the first solo exhibition devoted to this artist in the U.S., at the Peridot Gallery in New York in 1959-60. The Peridot Gallery, run by dealer Louis Pollack, was known for promoting American Abstract Expressionist painters, but it also played a vital role in the dissemination of Rosso’s work in the U.S. Joseph Hirshhorn, for example, bought at least eight bronzes and waxes from Pollack, which today are at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

I was also very interested in studying the scope of the Italian art market in America, during a period defined by two significant events: the exhibitions XXth Century Italian Art and Italian Art from American Collections, organized by the Museum of Modern Art respectively in 1949 and 1960.

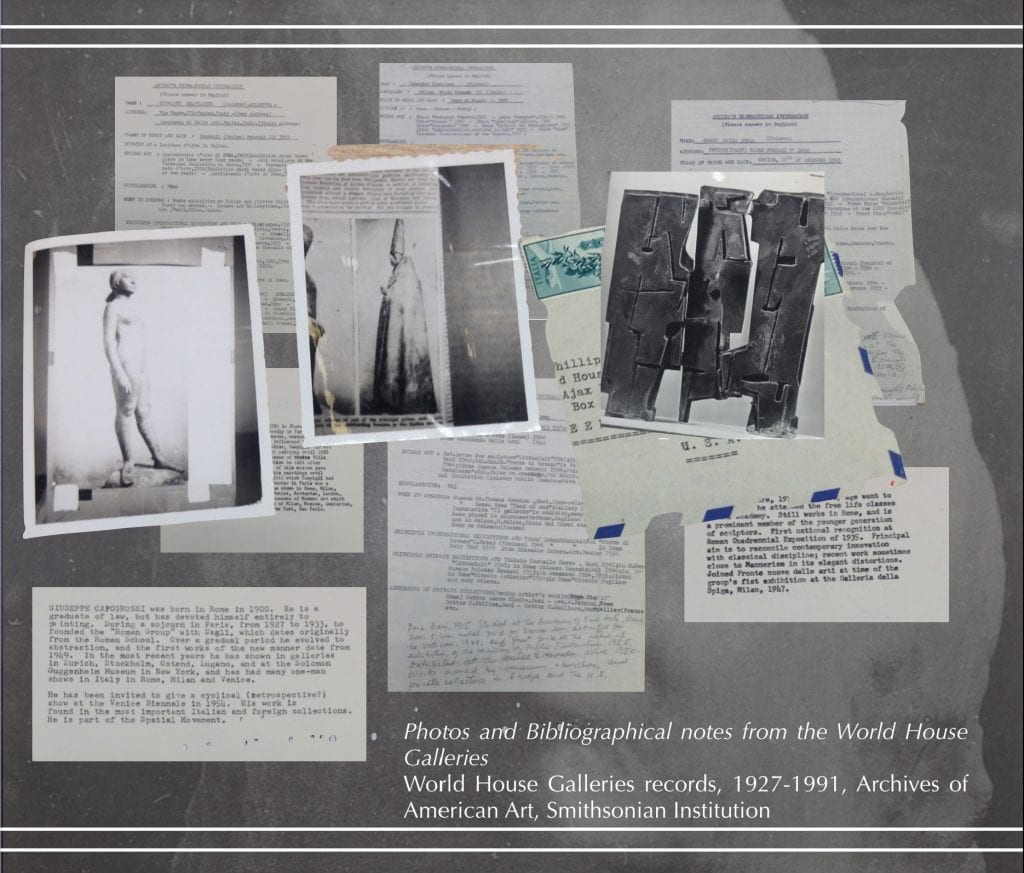

There were numerous collections at AAA relevant to my research: the James Graham & Sons Gallery records; the Catherine Viviano Gallery records; and the World House Galleries records, to name just a few.

Catherine Viviano Gallery promoted contemporary Italian art, bringing works by Afro and Mirko Basaldella, Fausto Pirandello, and Renato Birolli to the U.S.; the World House Galleries also specialized in Italian art, and among their artists were the major sculptors Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù. I had the privilege of presenting a paper on this material at the College Art Association in February.

![]()

Sometimes the best discoveries come from unexpected directions. While I was in Washington I shared the theme of my research with another Italian visiting scholar working there, and one morning, in the silence of the archive, she shouted out my name. Inside the records of the Finch College Museum of Art, she had discovered a file on Medardo Rosso, which had not been indexed or tagged as such! What a serendipitous find! Alerting the AAA staff to this discovery, to enable them to catalogue it properly, gave me the sense of having contributed, in some way, to the exceptional world of the Archives of American Art. Finally, I would like to dedicate a special thanks to Joy Goodwin, Archives Specialist at the New York office; she patiently put up with me and my requests almost every day during these last six months!