Earlier this month, during Frieze and the other art fairs, hundreds of artists from all over the world came to New York and distributed business cards featuring their website or flashed their iPads to show their portfolio.

Earlier this month, during Frieze and the other art fairs, hundreds of artists from all over the world came to New York and distributed business cards featuring their website or flashed their iPads to show their portfolio.

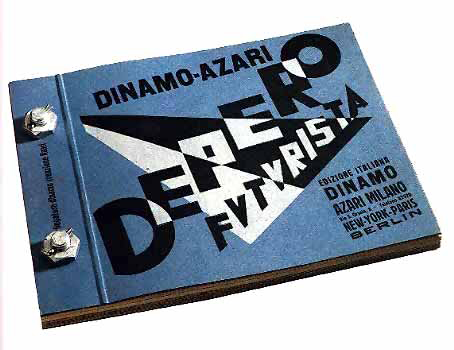

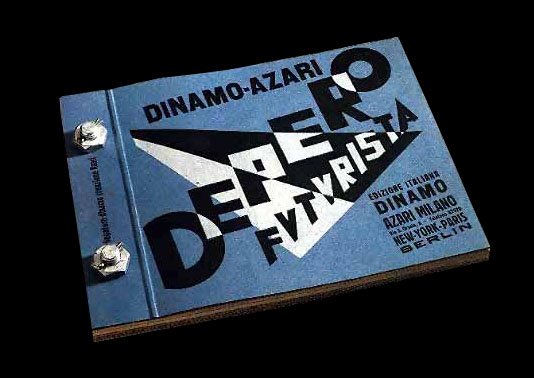

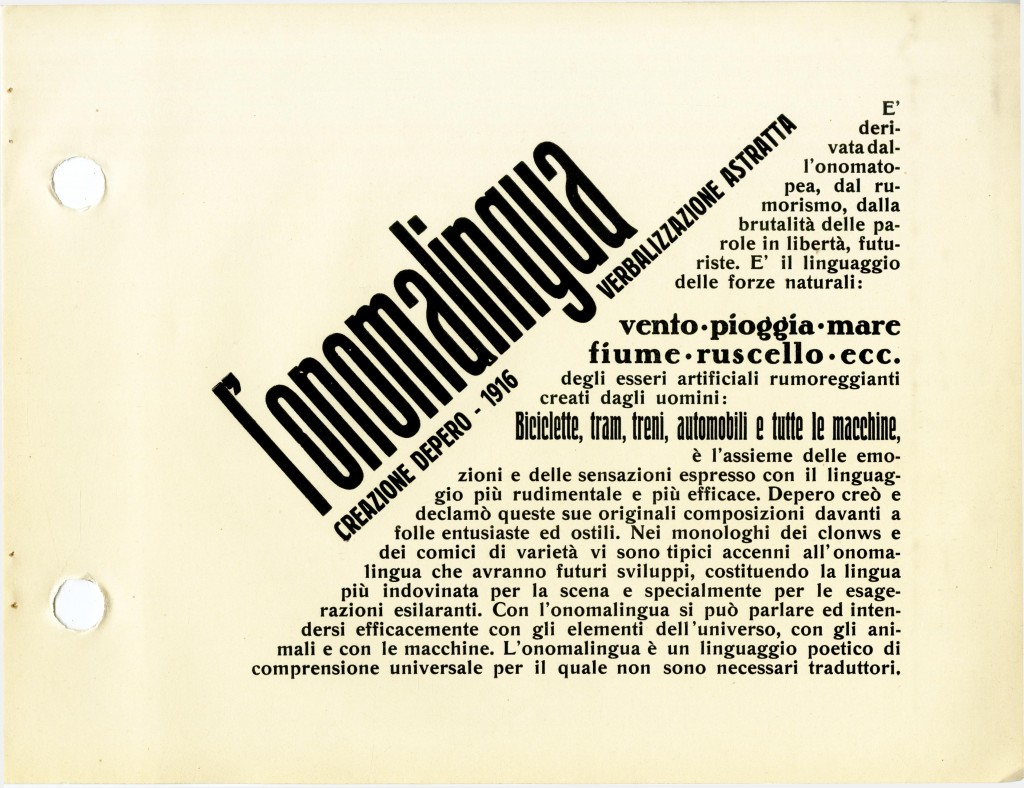

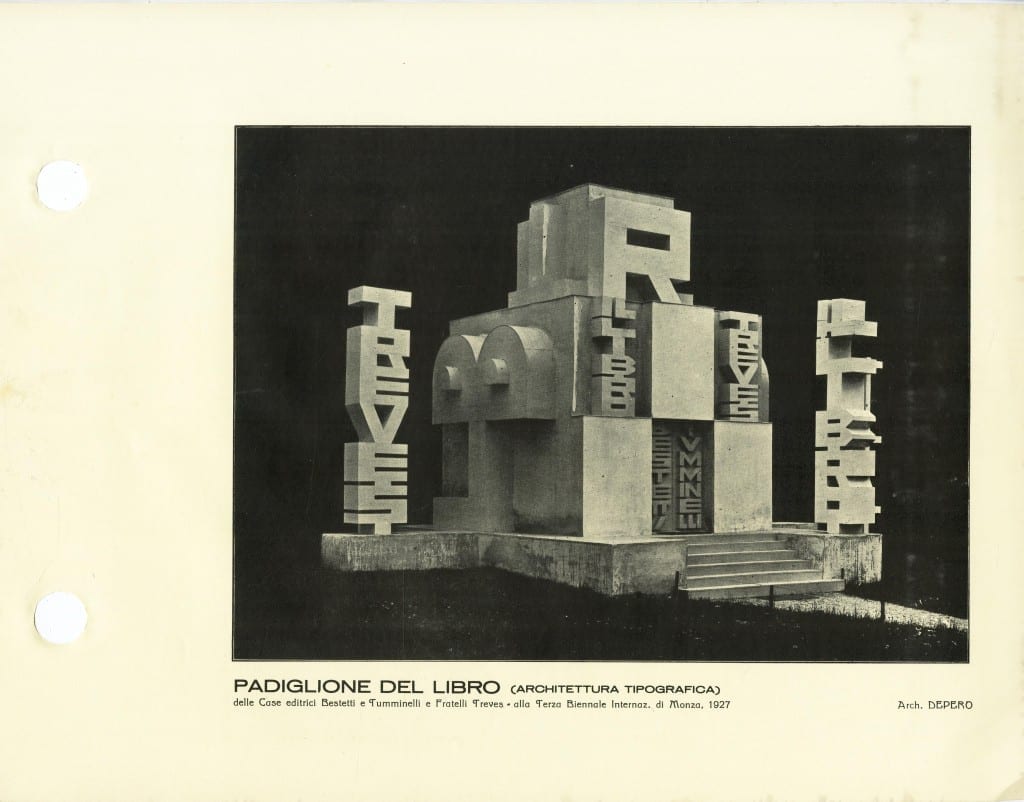

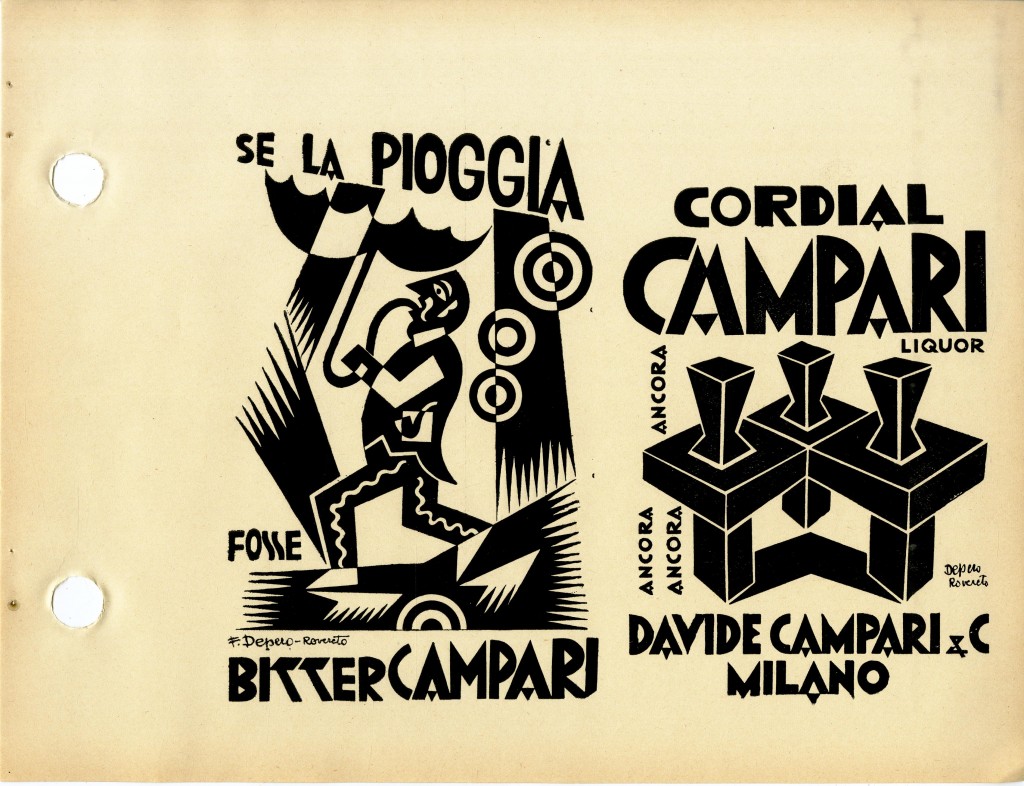

When Fortunato Depero and Rosetta, his wife, came to New York in 1928 they shipped 500 of the artist’s works, hoping to conquer the American art world and market. They also brought several copies of Depero’s book, Depero Futurista. This book is also known as the “bolted book,” on account of its unique binding. It was printed in 1927, in an edition of 1000 copies. The book was like a portable museum. It included the most important achievements of Depero’s career, highlighting the many fields his work encompassed—from writing, painting, sculpture, and architecture, to tapestry, furniture, toys, theatre, advertising and more. A decade earlier, in a famous 1915 manifesto, Depero together with the older Futurist artist Giacomo Balla had theorized the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe. They proposed a utopian transformation of every aspect of life into a total, multi-sensory work of art. The “bolted book” documented how Depero had done just that. While making paintings and sculptures, he also produced pillows, fabricated toys and designed entire buildings. He merged the boundaries between high and low, between art and life, between artisanal and industrial.

The book itself was no traditional artist’s monograph. Held together by industrial nuts and bolts, it was a mechanical book that could easily belong to the robotic figures from Depero’s paintings. It was also destructive; it challenged the humanistic cult of the library. If you placed it on a shelf, it would damage the neighboring volumes with its metallic protuberances.

Advertising played an important role in the Bolted Book at many levels. The volume dedicated many pages to reproductions of Depero’s ads. It also included his “Manifesto to the Industrialists,” where he compared the modern billboard to the altarpieces of the Renaissance. Above all, it advertised Depero’s virtuosity as a graphic designer. The book was, in fact, a form of self-advertisement in and of itself. Depero distributed it to potential clients when he was seeking work. And he exhibited it “unbolted” as a ready-to-use solo show, like CIMA has done.

Depero Futurista anticipated some key features of Marcel Duchamp’s Box in a Valise, which was described by the latter as a “portable museum.” It is very likely that Duchamp saw Depero’s book before he began the Box project in 1935; the Société Anonyme, run by Duchamp and Katherine Dreier, publicly endorsed and sponsored Depero’s 1929 show at the Guarino Gallery in New York. They also purchased one of Depero’s collages and published two images from the “bolted book” in the Société’s magazine, Quarterly Brochure.

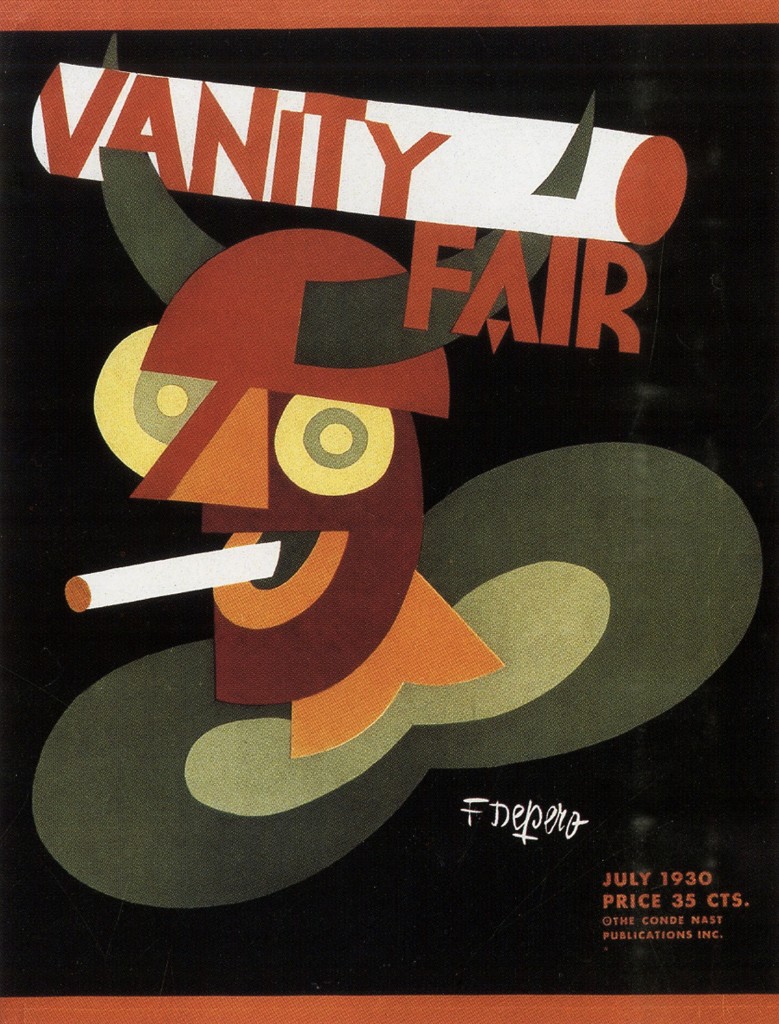

In New York, Depero’s paintings failed to sell, but the “bolted book” proved successful in getting him commissions outside of the art world. This is no surprise, given that Macy’s, Vanity Fair, and the Roxy Theater on Broadway were more exciting to Depero than the newly founded Museum of Modern Art (which he never visited in two years of living in NYC). In New York he found that “powerful skyscrapers, fabulous bridges, quickest railways elevated and underground ones, forests of ships … are magnificent impressive shows of modernity.” Today, Depero would probably have skipped Frieze. He believed that the modern fabric of the city itself was the best contemporary art.