The Matthew Marks Gallery is currently showing an exhibition of photographs by Luigi Ghirri, a land surveyor turned artist who was among the first in Italy to elevate color photography to the status of artistic expression.

Born in 1943, Ghirri began working with photography as a form of art in the 1970s. Traveling through the cities, agricultural landscapes, and tourist localities of his native Emilia Romagna, Ghirri developed a vast corpus of images that document and investigate the spaces, objects, and people of a region caught between its agrarian past and its touristic development, between domestic economies and consumerist culture. The photographs display, through a whirlwind of visual inputs that are very familiar to anyone who has lived during the 1970s and 1980s, the mix of familiarity and disorientation that characterized those years. It is a tour de force that carries the gravitas of the serial, methodical inquiry, and also a nostalgic longing for a distinctly Italian landscape that today has grown harder to recognize, and harder to transform into art.

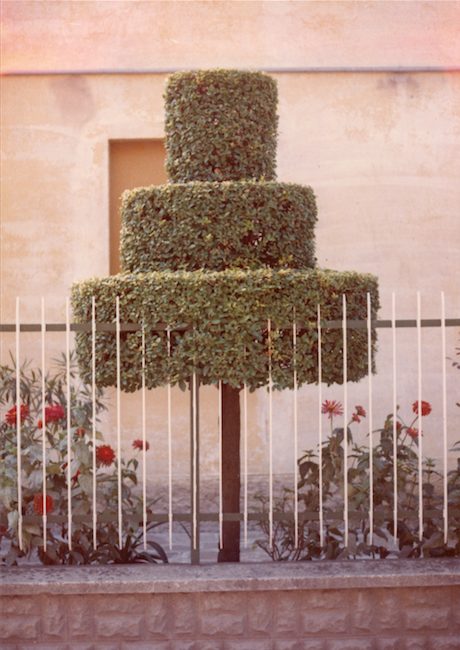

Cervia, From the series Paesaggio Italiano, 1989

Installed in three consecutive rooms, the artworks of Impossible Landscapes provide a satisfactory overview of Ghirri’s multiple lines of aesthetic and sociological inquiry. The exhibition represents, in a sense, an archival sampling of a much broader corpus of evidence. We observe semi-abstract close-up shots, depicting the patterns of tiles or the pebbles on a dirt road; desolate urban landscapes, where nature and architecture clash to impose their unique type of monotony, as well as an almost metaphysical suspension of time; and marine landscapes, where a humble humanity of bathers finds solace under a scorching sun and amidst the omnipresent signposts of consumerist culture.

Ghirri’s photographs survey the quotidian and the domestic, the casual and the happenstance, the vulgar and the commercial, with a mix of irony and deference. The subjects and compositional choices demonstrate that Ghirri’s eye was well aware of modern and contemporary artistic discourse: his patterns of tiles and pebbles suggest the observation of works by Piet Mondrian and Informal Art, the photographs of lacerated billboards hint at the work of Mimmo Rotella, while the magazine spreads surrounded by Coca-Cola ads create a “ready-made” photo collage, in which the task of the artist is simply to recognize and document the artistic quality of everyday life. Furthermore, the viewer is often prompted to question the unique framing of scenes and objects: the casual juxtaposition of elements constantly intermixes with the clear perception of a studied framing, creating the impression of photographs that document a conceptual art project, an intervention of landscape art, or an Arte Povera installation.

Most of Ghirri’s photographs were printed in small format, often as small as 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 inches: these minuscule dimensions, along with the patina of thirty-year-old prints, creates a special bond with the viewer who can still recall the familiar size and feel of objects now obsolete, displaced by digital cameras and sophisticated smartphones. Ghirri’s prints speak to a world in which the circulation and fruition of images was still frequently anchored in a physical, tactile experience. Observing them led me to wonder what Ghirri’s art could have been today, at a time when technologies such as Google Streetview have already captured, with their own brand of seriality and gravitas, and with their disembodied grasp of aesthetics, the changing landscape that surrounds us with its signs and meanings.

At the Matthew Marks Gallery, 526 West 22nd Street, until April 30, 2016.