Alberto Burri: the Trauma of Painting opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim last month, concurrent to the Center for Italian Modern Art’s annual exhibition, Giorgio Morandi. The first American retrospective of Burri in nearly forty years, it is also the largest ever. Guest curated by Emily Braun, distinguished professor of art history at Hunter College and The Graduate Center, CUNY, and a member of CIMA’s advisory committee, the show displays a substantial number of works spanning Burri’s entire career, thus reestablishing his pivotal position in postwar art history. As the exhibition demonstrates and the catalogue forcefully argues, Burri responded to the psychological and concrete wounds of World War II in a singular and influential way. Distancing himself from both the lyrical gestural abstraction of Informel (the European equivalent to Abstract Expressionism) and the base materialism of art brut, Burri restaged the war traumas onto the body of painting in a salvaging–if extreme–operation. Encountered in person, his sculptural paintings are as repulsive as they are tasteful. Refusing conceptualization, Burri’s works put their materials, colors, and processes to the forefront, presenting the viewer with real “emotionally competent stimuli” and ultimately appealing to the tactile rather than the visual brain.

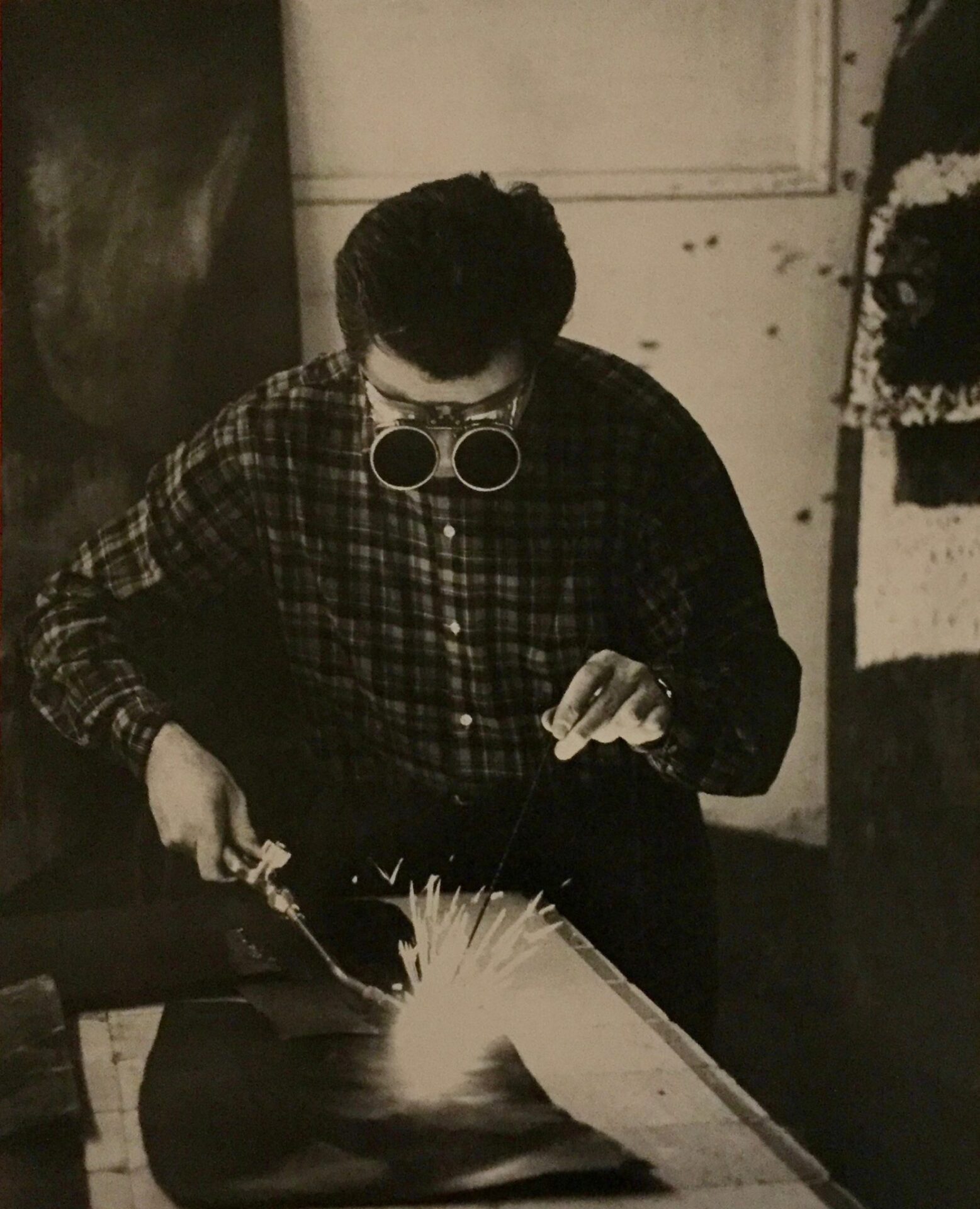

On view are more than 100 works produced between late 1940s and late 1980s. Grouped by series and installed in rough chronological order, Burri’s oeuvre unwinds along the ramps of Frank Lloyd Wright’s landmark building. The early work–smaller in size, more heterogeneous in terms of materials, and additive in process–occupies the lower levels of the spiral. Between 1948 and 1952 ca. Burri made the Catrami (Tars), accretions of tar with different levels of blackness; the intimate Muffe (Molds), approximating bacterial invasion via crusts of inert material; and the sculptural Gobbi (Hunchbacks). In 1950 the artist made his first Sacco (Sack) from cast-off burlap bags, moving towards the use of a single material that he worked from front and back. Ascending the spiral the work becomes larger in size. From the mid-to-late-1950s, as Italy entered the economic boom, Burri started using materials of building and industry, including the Legni (Woods), burnt wood veneer at different gradations; the imposing Ferri (Irons), with more or less protruding surfaces; and the Combustioni Plastiche (Plastic Combustions), torched colored or transparent PVC. At the top of the spiral, the late paintings,

Cretti (Cracks) and Celotex, are enormous, elegant, and calculated. The works are bracketed by two video projections. In the rotunda is a documentary film from the 1940s showing the rubble of bombed Italian cities, while on the upper level is a film the Guggenheim commissioned from the Dutch filmmaker Petra Nordkamp. It documents the Grande Cretto, 1985-89, an impressive Land Art memorial Burri designed to honor the town of Ghibellina, Sicily, devastated by an earthquake in 1968.

Each series take their name from the unorthodox materials Burri used, pushing them to their extreme physical limits through operations such as stitching, burning, torching, and suturing.

In spite of the semiotic richness of the works, the tautological titles express the artist’s refusal to associate his production with any external reference. As art historian Giulio Carlo Argan perceptively realized already in the early 1950s, Burri’s paintings function as “reverse trompe-l’oeil, in which the picture no longer imitates reality, but reality imitates a picture.” Building upon this and other interpretations, Emily Braun’s catalogue essay culminates in a convincing analogy between Burri’s irreducible “material realism” and Italian “neorealism” in cinema. As neorealism’s “reconstituted reportage,” i.e. the deployment of both actual and simulated documentary footage to attain the utmost naturalism, Burri’s paintings depend on visual plenitude to depict material deprivation. Ultimately, Burri inflicted authentic trauma onto the body of painting in order to keep it alive.

Born in 1915 in Città di Castello, Umbria, Burri grew familiar with the art and history of his region, from the fifteenth-century master Piero della Francesca to Saint Francis of Assisi, the patron of the poor. A fervent believer in the fascist regime as a young man, in 1935 Burri interrupted his medical studies to volunteer as a field doctor in Mussolini’s war against Ethiopia. In 1940 Burri graduated in medicine and surgery. He fought in Yugoslavia the following year, after which he requested to be transferred to the medical corps. He was taken prisoner by the British in 1943 while in service in Tunisia, and between 1943 and 1946 he was incarcerated in a U.S. internment camp for Italian prisoners of war in Hereford, Texas. Repatriated in 1948, Burri abandoned the medical profession and thereafter dedicated himself to art. Self-taught, in 1948 Burri traveled to Paris and quickly absorbed the lessons of artists such as Mirò, Dubuffet and Fautrier, whose practice desublimated painterly matter. However, Burri was to be neither a lyrical nor a base materialist artist. Back in Italy in 1949, the artist moved to Rome where he befriended artists and gallerists, though he never joined any of the more or less engagé artists groups nor signed manifestos. Thereafter he would go on to reinvent the tradition of painting by using unorthodox materials and pushing them to their extreme physical limits.

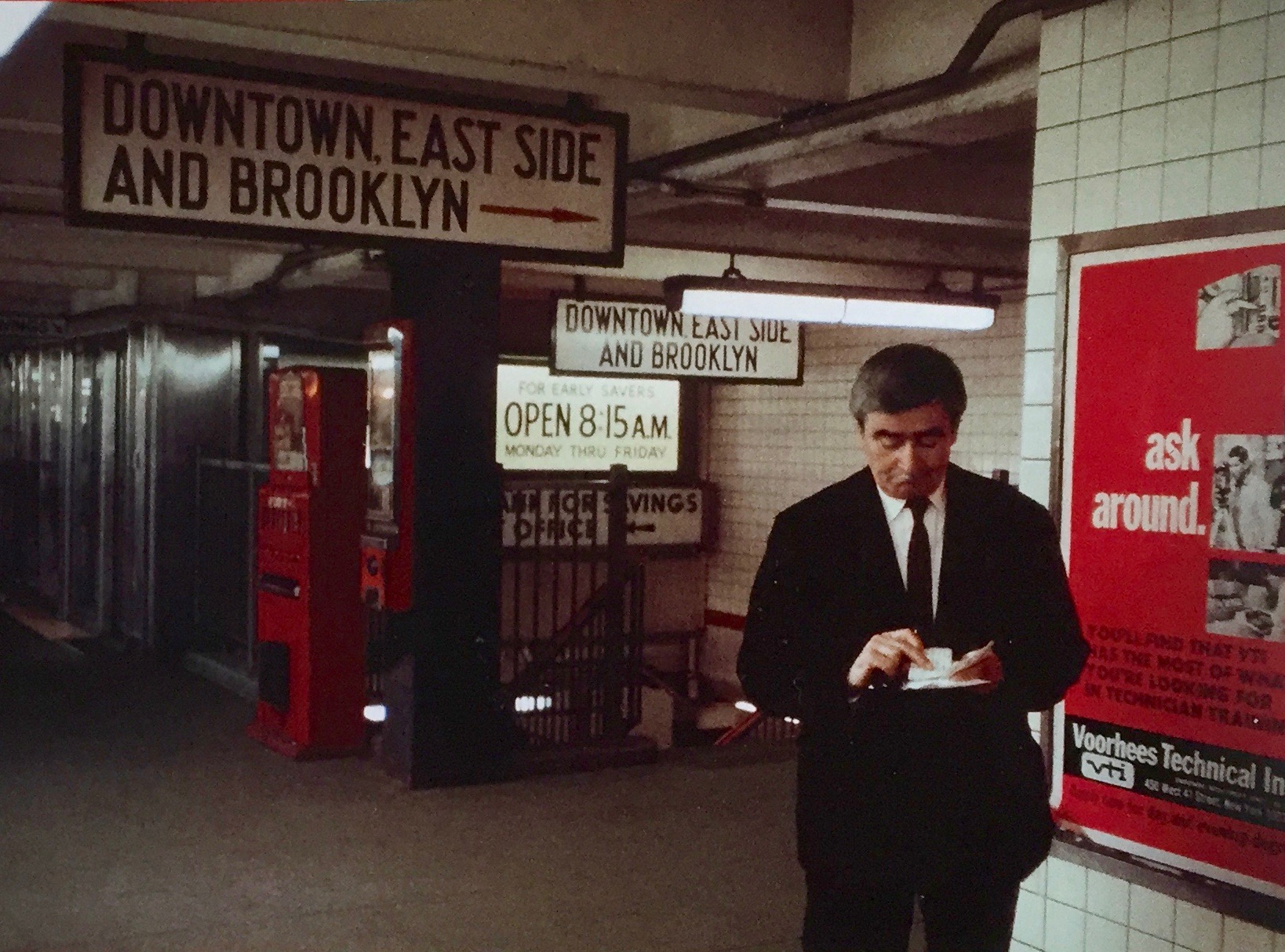

The exhibition reminds us of Burri’s biographical connection to the U.S. He became an artist while a prisoner of war in Texas; had exhibitions early on in American galleries and museums; married an American woman, the dancer and choreographer Minsa Craig; and spent many winters in Los Angeles. Moreover, the show renews the long-lasting relationship between the artist and the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum. Burri and James Johnson Sweeney, the Guggenheim’s first director, met serendipitously in Rome in 1953. Sweeney henceforth became one of Burri’s most indefatigable supporters. He included one Sacco in the exhibition Younger European Painters at the museum later that year, wrote the first English monograph in 1955, and presented one of Burri’s Legni in the inaugural show of the Frank Lloyd Wright building in 1957. The museum went on to acquire those and other works, as well as hosting the touring monographic exhibition of the artist in 1979–the last major Burri show to take place in the US. Among the highlights of the current show are the sixteen miniatures that Burri carefully crafted for Sweeney as Christmas presents, each reproducing in scale one of his works from each of the different series he produced.

Hovering between surgical suture and haute couture, this masterfully presented, comprehensive exhibition of Burri’s radical work is a must-see.